A naturally occurring group of fungi shows promise with nitrogen reduction and other pastoral benefits. Anne Lee reports.

In what may be a world first, Lincoln University scientists have identified specific groups of naturally occurring fungi that can help cut nitrate losses and lower nitrous oxide gas emissions, all while helping boost pasture production and potentially improve drought tolerance.

In what may be a world first, Lincoln University scientists have identified specific groups of naturally occurring fungi that can help cut nitrate losses and lower nitrous oxide gas emissions, all while helping boost pasture production and potentially improve drought tolerance.

The findings are a result of almost 10 years of work by Professor John Hampton and Dr Hossein Alizadeh who are continuing to research the effects of these specific fungi with the view to developing commercially available, biological products with Ravensdown that could be available to farmers by 2026. The products are expected to be a seed coating for pasture species or a prill that can be drilled into existing pasture.

It’s part of Ravensdown’s N-Vision NZ suite of nitrogen loss management technologies that will also include new, next-generation nitrification inhibitors and a nitrogen decision support tool.

The nitrification inhibitor work is being carried out by Lincoln University soil scientists led by Professors Hong Di and Keith Cameron. While more details on the nitrification inhibitors are yet to be revealed, the scientists working on the fungi have been able to share their results so far on what the tiny microbes can do to significantly help farmers lower their environmental footprint.

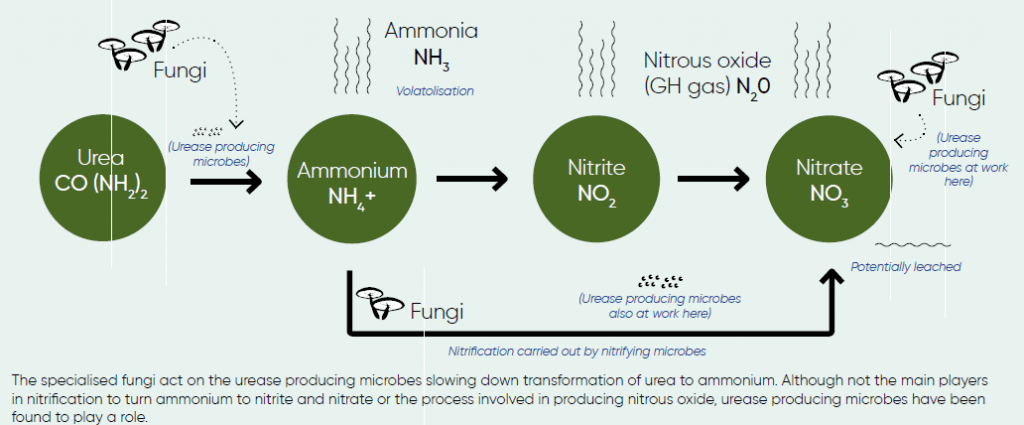

Indications are that the microscopic microbes can pack a powerful punch to other soil dwelling bedfellows of the bacterial kind involved in the nitrogen cycle. Those bacteria produce urease which is an enzyme that’s critical for the very first step in the nitrogen cycle – the breakdown of urea to ammonium.

Indications are that the microscopic microbes can pack a powerful punch to other soil dwelling bedfellows of the bacterial kind involved in the nitrogen cycle. Those bacteria produce urease which is an enzyme that’s critical for the very first step in the nitrogen cycle – the breakdown of urea to ammonium.

They don’t completely stop the process because of the sheer number of urease-producing bacteria but they do slow it down which is why they can create a win:win situation.

Win one – Less nitrogen is lost either as nitrous oxide to the atmosphere or as nitrate through leaching. Win two – Urea-N remains available longer so plant growth is improved.

Hossein says studies have found that the urease producing bacteria are involved in other important steps further along in the nitrogen cycle: –

- The nitrification process – the step in the nitrogen cycle where ammonium goes to nitrite and then readily leached nitrate.

- Production of the potent greenhouse gas nitrous oxide from nitrate.

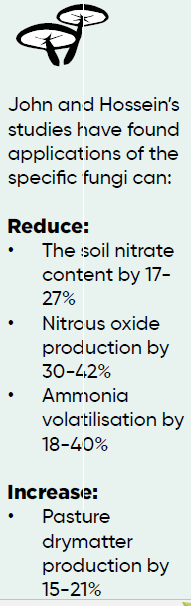

John says the results have consistently been within the ranges they have found in field trials from across the country and across soil types.

One study has found responses right out to 15 months but research is underway into how often applications need to be made.

Indications are that it could be annually, John says.

The work to find the beneficial fungi started way back in 2013 and likening it to finding a needle in haystack is severely diminishing just how gargantuan the task has been.

AGMARDT funding for a post-doctoral study back in 2013 enabled Hossein to begin his quest by first establishing what urease producing microbes were in dairy pastures. The Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE) then came on board to help him continue his studies into narrowing down fungi species which could help slow the process down.

He’s dug into dairy pastures across the country, hunting out strains of fungi from a specific species in a huge screening project to find out effects they could have on soil bacteria.

John says they isolated about 300 beneficial fungi and screened them one by one.

So far they have three to four strains that they’re confident can produce the beneficial results.

“It’s been a huge amount of work to find them,” Hossein says.

Over the past four years they’ve been following up glasshouse studies with research out in dairy pastures in regions such as Southland, Canterbury, West Coast, Manawatu, Waikato and King Country looking at the effect on the breakdown of urea in the nitrogen cycle following application of the beneficial strains of fungi.

They’ve used urea where the nitrogen has been “tagged” with an isotope so they can follow its progress and be sure it has come from the urea they applied and not nitrogen that was already immobilised in the soil.

The next phase of research, being funded by the Ministry of Primary Industries (MPI) Sustainable Food and Fibres Futures fund and Ravensdown, will check if similar reductions in nitrogen loss from urine patches can be achieved and what happens with pasture production. It will look further into other beneficial effects of the fungi and delivery systems into pastures.

John says having spores inoculated into the seed coating is an ideal way to get good establishment of the beneficial fungi populations because it puts the fungi into close contact with the new plants’ roots.

“Sowing” prills into the soil also has the effect of depositing the fungi close to the roots.

Activating a defence responseDrought tolerance is another “line of inquiry” for the team at Lincoln. In a separate $10.7 million funded MBIE Endeavour project they are looking at what effect the presence of certain volatile compounds produced by fungi have on pasture plants’ activation of their defence systems.

“There’s some evidence that in the presence of certain microbes plants can change their defence systems against stress.

“We know that microbes can use chemical signalling picked up the plant roots that induce a defence response to an impending attack – that could be from insects or pathogens, heat or drought stress,” John says.

The scientists will be looking at the volatile organic compounds produced by the microbes and how they interact with pasture plants, developing an understanding of what happens in the plant and then working on how this could be used to ensure pastures are more resilient.