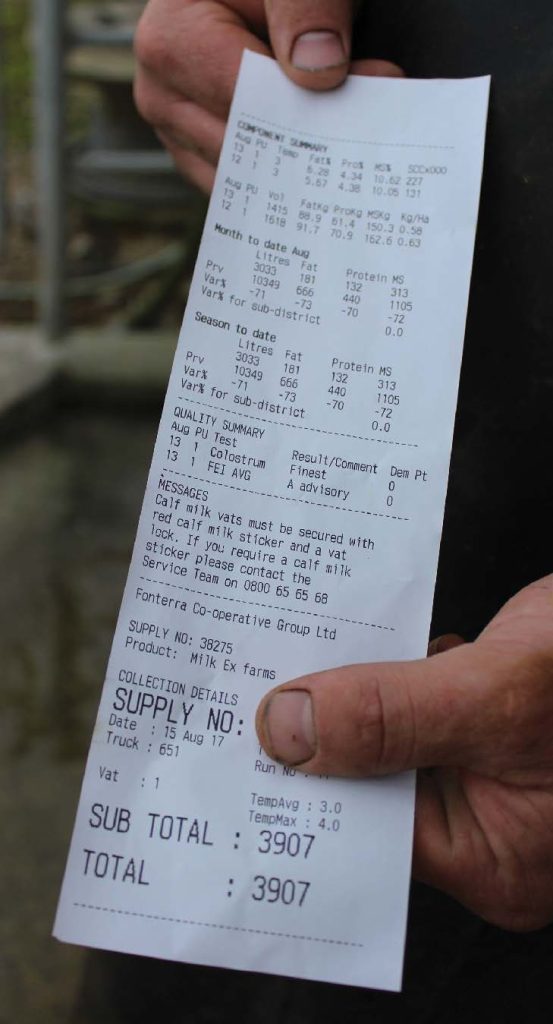

The milk docket left after a milk tanker makes a collection from a dairy farm contains a lot of information for the farmer.

That white slip of paper the money truck, sorry, the milk tanker, leaves at every pickup should not be left fluttering in the wind on its clip.

That white slip of paper the money truck, sorry, the milk tanker, leaves at every pickup should not be left fluttering in the wind on its clip.

Your milk docket is a mine of information and deserves more than a quick glance. If you can’t be bothered filing it for future reference, at least look at the figures on your milk company’s app.

They’re making it as easy for you as possible to access all the information so don’t ignore it.

Of course, you always check the milk temperature figure and milk quality for anything that is an alert and shows you’re possibly heading towards a grading.

And it’s easy to check the production figures too, making sure you’re heading in the right direction, whether it’s upwards at the start of the season or downwards at the end. And to give yourself a pat on the back when you’re above for the month and season to date compared with the last, or at least blame it on the weather if you’re not. But analysing those production figures closely will give you some clues about what is going on with your cows especially if you know what normal looks like.

Cows’ protein and fat percentages will naturally sharply decrease following calving as volume increases. About two months into the season, they should gradually start to increase until at the end of the season they are again high.

If they’re not, start looking at what your cows are eating.

If your protein percentage is lower than it should be for the time of season, the reason will probably not be a lack of protein in the cows’ diet.

For a cow to make milk protein it needs energy and that comes from carbohydrates so feeds high in fibre but low in carbohydrates, like hay and straw, usually decrease the protein in the milk.

They will probably also increase the fat percentage and as you get paid for protein and fat, you shouldn’t be concerned right? Wrong.

If your cows are suffering from a lack of energy, especially coming into mating and afterwards, then they won’t cycle and they won’t stay in calf. Aim to have that protein percentage gradually but steadily climbing before mating starts and keep it that way for the rest of the season. It’s showing you your cows have enough energy to produce milk and reproduce. If you can’t do it with the grass that you have, then it’s time to add something else to their diet such as grain.

The fat percentage rises at a slightly higher rate than protein throughout the season but if it starts climbing too much it could be a sign that things are also not right.

Ketosis is something you should always be watching out for in your cows but often the early signs in their behaviour can be hard to pick up so look at your milk docket as well.

Ketosis is when the cow is in a negative energy balance and is using the fat off its body to stay alive. The body fat is converted to ketones, hence the name, which the cow can use for energy and it shows up in a higher-than-normal fat percentage in the milk.

Physical signs of ketosis include lethargy, not eating and even aggressive behaviour, all which can easily lead to a wrong diagnosis. A blood test will identify it but keeping an eye on your fat percentage will give you early clues.

However, other things will also increase the fat percentage, such as feeding palm kernel which contains fat, and bypass fat which is so-called because it bypasses the rumen. They’re also known as rumen-protected fats for the same reason.

Rumen acidosis, either subclinical or clinical, could be yet another reason your milkfat percentage is lower than it should be.

It’s when there is not enough fibre in the cows’ diet or there is too much water-soluble carbohydrates (the sugars sucrose, glucose and fructose) or a combination of both.

It’s normally seen in dairy cattle in New Zealand when they’re introduced to fodder beet as a winter feed when they’re no longer milking, but if you’re adding a high sugar feed into their diet when they are still coming into the dairy, watch your milk docket to make sure the milkfat percentage is staying where it should be.

Severe acidosis can result in cows going down, coma and death within eight to 10 hours. Also look at your milk urea figure (MU). It’s the measure of protein available to the cow but also an indicator of rumen efficiency.

Less than about 16 is showing not enough protein is in the diet and more than about 35 shows high dietary protein or the rumen is not working well enough.

This is because if there is too much protein entering the rumen, and there are not enough microbes in the rumen to convert it as they should be doing, then the excess nitrogen from the protein is absorbed through the rumen wall into the bloodstream and converted to urea in the liver.

Most of it is excreted in the cow’s urine but some passes into the milk and shows up in your MU figure.

A high MU figure in pasture-fed dairy cows will not affect their health or reproductive performance.

It just means you are feeding a whole lot of protein to your cows that is being wasted and possibly ending up in your farm’s waterways and causing problems there. It’s the cow equivalent of “pissing it up against the wall”.

If you are only feeding pasture, relax, there’s not a lot you can do but if you are paying for high protein feeds as well maybe start reducing them.

Fonterra, in 2017, also added the FEI (Fat Evaluation Index) figure to the docket. It’s because milk with a high FEI is harder to make into a variety of its products. It has nothing to do with the health of your cows.

A high FEI will result in a grade so watch it closely, just as you do with thermodurics and milk temperature and everything else to do with milk quality.

The main cause of high FEI is feeding too much palm kernel which is high in fat. There are ways to manage it, by making sure you are not feeding anything else which can affect the figure like fodder beet or other feeds high in starch and sugars.

It can also be a problem in late lactation and when milking less than twice a day, when milk volumes are less.