An equity partnership gave a Canterbury sharemilking couple a stake in something much more permanent and an opportunity to put down roots. Anne Lee reports.

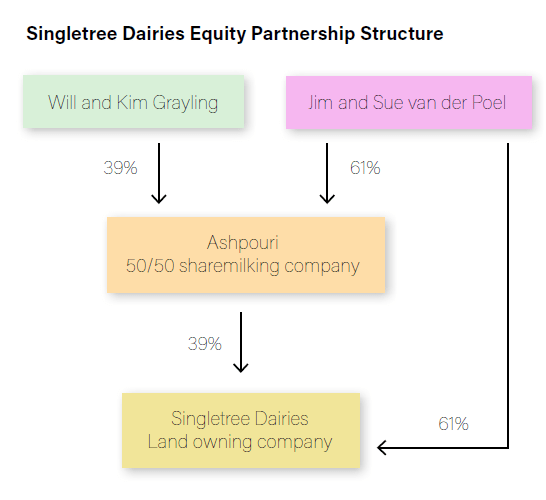

A novel equity partnership structure where a sharemilking equity partnership also has an ownership stake in the landholding company has been a proven vehicle for equity growth.

A novel equity partnership structure where a sharemilking equity partnership also has an ownership stake in the landholding company has been a proven vehicle for equity growth.

It’s enabled one partner to grow their slice of the pie and now, 10 years later, it’s also enabled both partners to grow the size of the whole pie with a new farm investment that’s also bringing on a new equity partner, keeping the cycle of growth rolling on.

Canterbury dairy farmers Will and Kim Grayling started out with 28% share of an 1800-cow sharemilking business, Ashpouri in 2013.

Their partners in the business are well-known Waikato farmers Jim and Sue Van der Poel.

Back when the alliance was formed the sharemilking business also took a 28% stake in the landholding company Singletree Dairies.

Will had been working for the van der Poels as a farm manager on one of their farms in a previous larger-scale equity partnership company Spectrum Group.

When that group restructured to allow partners to create other entities, two dairy farms the van der Poels took sole ownership of were Singletree Dairies and Chertsey Dairies.

When that group restructured to allow partners to create other entities, two dairy farms the van der Poels took sole ownership of were Singletree Dairies and Chertsey Dairies.

That process coincided with Will and Kim looking at what their next options were for growth.

Both are Lincoln University graduates and Will was New Zealand Young Farmer of the Year in 2011.

By 2013 large scale sharemilking was still out of reach for the couple but the equity partnership in the 1600- cow sharemilking business gave them an opportunity to generate good cash flow.

For the van der Poels it meant partnering with proven performers and for Will and Kim it gave them a stake in something much more permanent and an opportunity to put down roots.

They earned income as equity managers and also shared in the profits from Ashpouri.

Ashpouri received 28% of the landowner’s profit and Will and Kim then received 28% of Ashpouri’s profit – which is the profit from the sharemilking venture plus the 28% share of any profit from the landowning entity.

Growth opportunities were quick to come with the 464ha Singletree Dairies expanding to 625ha and 2400 cows within two seasons and Ashpouri also taking on the sharemilking job for 210ha Chertsey Dairies.

The expansion of Singletree Dairies grew the pie for both parties.

The sharemilking business has expanded too over time and now includes 3500 cows.

“We’ve chipped away a couple of times since 2013 purchasing a little more each time in terms of percentage so now we have a 39% stake in Ashpouri and that has a 39% stake in Singletree Dairies,” Will says.

“The beauty of the equity arrangement with the sharemilking business having a share in the land holding company for both parties is that we do what’s best for the business as a whole.

“We don’t favour the sharemilking business for instance or choose not to spend money or invest in things that are benefiting the land holding company,” Kim says.

During the earlier 2000s the rapid escalation in land value was a key driver of equity growth.

That came to an end and cash again became king with successful dairying businesses driven by profits.

Having a profitable operation is key to equity growth, Will says.

And doing that means keeping a tight control on cost structure and optimising production with the golden rule of maximising the amount of top quality pasture eaten, he says.

Some might say the years of rapid land value rise were the golden years for dairy farming.

“But you could equally argue the last five years have been the best years to buy a farm because interest rates have been low, land values have been steady and cash returns have been higher than we’ve ever seen.

“Costs have gone up now and interest rates are rising, although they’re still lower than they were 10 years ago so there are still opportunities if you are focused on making a good cash return,” he says.

The biggest handbrake to their equity growth so far, hasn’t been profitability, but the spectacular slide in the value of Fonterra shares.

It’s real money and value wiped off their balance sheet in their eyes as well as the eyes of the bank.

“Yea, it’s disappointing and it did affect us taking on opportunities when the shares dropped (in value), so it’s very definitely real, not just on paper.”

New partner included

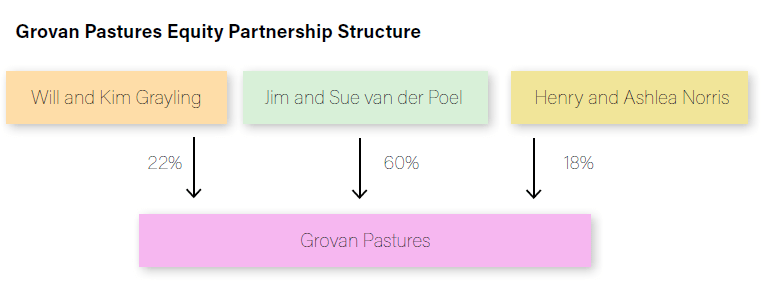

Last year though they were able to take on a new opportunity – another equity partnership.

While it’s again with the van der Poels, this one includes a new partner.

Henry Norris and his wife Ashlea have joined them in buying a 1300-cow property near Dunsandel. Henry, also a Lincoln University graduate, completed a Bachelor of Commerce Agriculture although he didn’t have his sights on dairying originally, working in other sectors for a few years.

Four years ago and new to dairying, he took on a job with Will and Kim as a herd manager at Singletree Dairies and after just two years stepped up to manage Chertsey Dairies.

After two years at that, he was keen to get his foot on the progression ladder so at the start of last year the couple were heading towards contract milking at Chertsey Dairies, starting in June 2022.

But when the new farm opportunity came up, Will and Kim and Jim and Sue offered Henry and Ashlea a chance to get involved there. Again the partnership wanted to create a win:win situation.

“We know Henry’s skills and strengths and that he’s a good operator. This was a chance to bring him along in the business,” Will says.

Like Will and Kim had been at the start, Henry and Ashlea weren’t quite ready to step up to a significant shareholding in such a large-scale farm.

But instead of a repeat of the equity sharemilking structure, the original partners decided a more straightforward approach was to lend the couple the shortfall on what they needed to be able to take an 18% share and become equity managers.

“One of the key values in equity partnerships is the ability to effectively leverage beyond what you can do by yourself,” Will says.

“For instance (not the numbers involved) if you have $300,000 equity and partners lend you $700,000 you can leverage yourself by 70%.

“The farm leverages 50% so your original $300,000 equity has $2 million working for you.

“That’s seven times your equity working for you and that’s the initial piece you have to understand.

“The second piece, which has been hugely beneficial to us, is the ability to chip away at a farm without having to buy and sell incrementally larger farms along the way, with all the risks that come with that each time in terms of finance, finding the right farm and of course moving everyone from place to place.”

For Henry and Ashlea the switch in mindset from going contract milking to weighing up the opportunity to become equity partners in a new farm all happened very quickly.

“We could have come here instead of the other farm as contract milkers but we didn’t know this farm and there’s risk in that – there’s risk in every situation but when we weighed it all up, this was a great opportunity,” Henry says.

It also gave a greater sense of partnership than a contract milking agreement.

The ability to have direct influence over building the value of the asset you have a share in, by improving it through good management and ensuring the farm performs well appeals. So too does having a progression pathway where they can build equity but stay put, especially now they have started their family with 15-month-old son Liam.

“Our initial plan is to pay down debt and build equity so we’re in a position to increase our shareholding,” Henry says.

Just like their original equity partnership, Kim says they openly and actively talk about intentions but they don’t lock each other into specific actions in the future by writing them into the agreement.

“The dialogue is very important so we’re aware of how each other is thinking – it means we’re more likely to be on the same page when it comes to the next move rather than something coming out of the blue,” she says.

“Locking people into buying or selling at a specific time is a great way to burn off a relationship too because it doesn’t take into account other opportunities or better ways of achieving the ultimate goal that are better win: win situations,” Will says.

To be successful equity partnership must ensure the equity manager has a meaningful percentage and that the equity manager is able to feel like the farm is their own.

“A two or 4% share is where that concept of golden handcuffs comes from.

“The equity manager just can’t make enough money to progress and that’s not win:win.

“If they don’t feel like it’s their own they’re less likely to have a long term view,” Will says.

That’s why it’s important to be sure your equity partners are aligned in terms of values, that the manager is capable of running a high performing farm and everyone’s intentions are in the open.

“Your equity partners have to be people you feel you can be vulnerable with.

“You have to be able to share your concerns as well as your successes,” Kim says.

Well structured and thought out legal agreements are important but if the partnership is working well, they won’t need to be referred to,” Kim says.

The agreement they signed 10 years ago is sitting in the cupboard, it’s never looked at and that’s because they have open and honest dialogue, they know each other’s intentions and there’s a healthy respect for what each party brings to the partnership.

There are high expectations for performance but there’s honesty and a culture of no surprises. Above all everyone approaches the partnership with a strong sense of fairness and a win:win ethos.

unning a high performing farm and everyone’s intentions are in the open.

“Your equity partners have to be people you feel you can be vulnerable with.

“You have to be able to share your concerns as well as your successes,” Kim says.

Well structured and thought out legal agreements are important but if the partnership is working well, they won’t need to be referred to,” Kim says.

The agreement they signed 10 years ago is sitting in the cupboard, it’s never looked at and that’s because they have open and honest dialogue, they know each other’s intentions and there’s a healthy respect for what each party brings to the partnership.

There are high expectations for performance but there’s honesty and a culture of no surprises. Above all everyone approaches the partnership with a strong sense of fairness and a win:win ethos.