The value difference between the good cow and the not-so-good is set to grow. Anne Lee reports.

THE VALUE GAP BETWEEN GOOD quality and poorer quality cows is likely to widen as environmental regulations begin to bite, the national herd heads towards a possible contraction and live exports cease. That could bring challenges but also opportunities to how cows are viewed as an asset.

Dairy cow numbers peaked at about five million in 2014 with numbers dropping but hovering about 4.9m since.

AgFirst agricultural economist Phil Journeaux says there’s now downward pressure on cow numbers as farmers look to farm systems solutions that enable reductions in nitrogen surpluses and greenhouse gas emissions.

“I don’t think we’ll see any crash in dairy cow prices but what we may see is the value of poor quality cows dropping

away and a greater differentiation in price,” he says.

High breeding worth (BW) and production worth (PW) cows will maintain their current value and may even see a lift as they become more desirable because of greater efficiency.

“We know from the work we’ve been doing on GHG modelling and farm systems options that a highly productive cow is going to be more desirable in terms of both financial return and not creating as many GHG emissions compared with a less efficient one.

“That’s going to be especially true after 2025 when GHG pricing mechanisms start biting.

“Work we’ve done shows that if you drop cow numbers by about 10% and lift the production of remaining cows – without increasing total feed inputs – GHG emissions drop by about 5% but the profitability of the farm business can be maintained.

“If you don’t lift the productivity of the remaining animals, farm profitability goes down very quickly.

Nitrogen and phosphorus regulations are ramping up too but can also be addressed in part by having fewer, more-efficient animals.

“If you can make the same amount of money by milking fewer cows, that’s going to solve a fair few environmental issues at the same time.”

“The main driver of cow values over the years has been the profitability of dairy farming but it’s also been influenced by other factors like demand for cows during those conversion years.

“Profitability will continue to be that fundamental driver but the factors that create price variations are changing.”

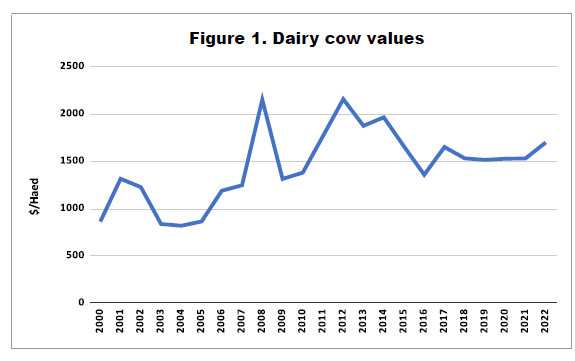

AgFirst managing director and agribusiness consultant James Allen says the cost of rearing a heifer to first calving will also continue to underpin cow prices. Over the last 20 years cow values have fluctuated but have trended upward. (See figure 1)

The issue has been, for those going into herd owning sharemilking as a pathway to farm ownership, that the lift in land values has far outstripped any increase in cow values.

“In 1992 it took 14 cows to buy a hectare of land, in 2016 it took 22 cows and now – at $1700/cow and $52,000/ha for land it would take 30 cows. You need more than twice the number of cows now as you did 30 years ago.

“Cows and herd ownership as an asset, especially for young people have been and still are a good asset base to get into.

“They provide a good return on investment and they can be bought in manageable lots.”

A widening gap in cow prices could mean opportunities – a lower cost of entry for some and a higher value herd for others.

DairyNZ system specialist Paul Bird says a third of contract milkers in DairyBase have an income derived from stock with their average net stock income $12,000/year. In 2021 the average herd owning sharemilker based on return on asset owned 500 cows and earned $93,000 in net livestock revenue.

The top 10% earned $142,000 in net livestock revenue which was about 12% of their total revenue. Generating income from stock sales can be an important part of sharemilker income as an add-on to profitably producing milk.

Return on assets from sharemilking have been difficult to beat and over recent years, with strong payouts, they have been particularly high.

“We’ve seen sharemilkers generating the value of their cows as revenue each year,” Paul says.

Extreme volatility during some periods has seen that return also fluctuate wildly.

There are risks that come with sharemilking in terms of milk price but also in the fact the job itself may not be secure, James says.

“It is also more difficult to secure larger sharemilking jobs.

“As well as a decrease in the number of farms we’re seeing a drop in the percentage of farms sharemilked.”

Over the last 10 years the percentage of 50/50 sharemilking jobs has dropped from 18.8% to 16.6% and the number of total herds milked in New Zealand drop from 13,892 in 2000/01 to 11,034 in 2020/21. The total number of 50/50 sharemilking jobs has dropped by 387 over that period.

“But stock are still a great means to get your foot on the progression ladder – as a contract manager or sharemilker,” James says.