By meeting a range of measures a Canterbury dairy farming couple have surpassed their nitrogen loss target. By Anne Lee.

By the end of this season dairy farmers in the Selwyn Waihora water zone must show they have cut their nitrogen leaching losses by 30% compared with the annual average loss between 2009-2013, their baseline period.

By the end of this season dairy farmers in the Selwyn Waihora water zone must show they have cut their nitrogen leaching losses by 30% compared with the annual average loss between 2009-2013, their baseline period.

For Tom and Sara Irving that means their nitrogen loss to water as measured by Overseer must be below 50kg N/hectare on average across their 124 effective ha home block and a 52 effective ha lease block which is part of the milking platform.

They’ve well and truly achieved that drop with their average number coming in at 28kg N/ha.

It’s taken investment in irrigation infrastructure, a slight drop in stocking rate, a big backing off in annual nitrogen fertiliser applications, a cut in bought-in supplement and a stronger focus on pasture management.

Milk production is still sitting at close to annual levels over the past six years at 1500kg milksolids (MS)/ha or 450-470kg MS/cow but back about 100kg MS/ha on the earlier, higher input years.

It’s hard to compare profitability between then and now on a status quo basis because so many variables have changed, not least the significant hike in milk price on one hand and the jump in input costs on the other.

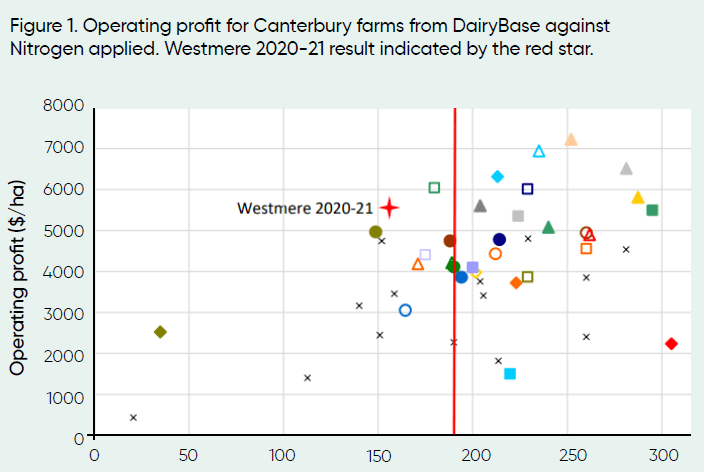

What’s clear from DairyNZ analysis though, is that the Irvings are sitting within the desired quartile when it comes to purchased nitrogen surplus, nitrogen use and methane production – each plotted against operating profit. (figure one.)

Tom says that while it’s a relatively comfortable position to be in as far as water quality regulations go, he’s aware there could always be more asked of the farm with new Essential Fresh Water rules still being worked into Canterbury and nationwide regulations.

The region has been working on water quality improvement for more than a decade through its Canterbury Water Management Strategy, zone committees and zone-specific rules that require seriously significant cuts to Overseer-estimated nitrogen leaching numbers.

Farm plans, land use consents and the long-signalled reduction requirements have been part of the landscape in the

region and farmers have been putting actions into place, some incrementally and some making wholesale farm system changes.

For Tom and Sara it’s mostly been a steady march of tweaks and shifts with a couple of significant moves along the way.

“There are still some levers we could pull – like plantain – if we were told we had to make further cuts.

“And the way things are moving that could happen but I’m fairly comfortable because I genuinely think that science and new technologies will take care of us with that.”

Tom and Sara keep their eye on research and development and are confident the efforts scientists are making will see new tools added to the tool box.

Conversion of Westmere began in 2009, the start of the baseline period, and didn’t include the lease block until the 2015/16 season. The addition of the lease land, converted from dryland sheep, has made for slightly more complex requirements in terms of nitrogen loss reduction expectations but the Irvings’ adoption of good and beyond-good management practices have helped them consistently go beyond regulated expectations.

Tom says when the home block was converted the milking platform was irrigated by a centre pivot and a Rotorainer which covered about 70ha.

Water was from a bore but with the advent of Central Plains Water the farm bought shares and switched to taking water from the large-scale scheme that brings water from the Rakaia and Waimakariri Rivers as well as Lake Coleridge, delivering it by gravity as it’s piped down and across the Central Canterbury Plains.

Two smaller pivots were installed to replace the Rotorainer which meant much lower rates of water can be applied over a more frequent return period. Lower irrigation depths at each watering event mean leaching is less likely. Along with those lower rate applications Tom is also able to apply water based on soil moisture monitoring information.

That means he can actively manage soil moisture to keep it high enough to provide moisture for pasture growth but not too high that they get drainage events – where soil moisture drains beyond the rootzone. That significantly cuts the chances of nitrate leaching further. It’s not a perfect science because it also relies on accurate weather forecasting of coming rain events.

Most years that’s not too much of an issue in the dry Canterbury region but thunderstorms or unexpected localised rainfall can still be possible on occasion.

Tom says in the early years after conversion they ran a higher stocking rate of about 3.6 cows/ha with a big focus on hitting low residuals and round lengths that could get down to 17-18 days during the high growth periods of spring. They bought-in more than a tonne of drymatter (DM) of supplement per cow then and Tom recalls they were often farming on a bit of a knife edge with pasture supply and demand through the peak growth period finely balanced.

“The cows would be pumping because the grass was like rocket fuel but it only needed a couple of days of colder weather and a small drop in growth rates and things crashed.

“You could be cutting silage one minute and feeding it out along with bought-in feed the next.”

Taking the pressure off a bit, dropping the stocking rate back to 3.3-3.4 cows/ha helped lower the need for as many bought-in inputs.

The inclusion of Viscount tetraploid ryegrass in the pasture mix during the renewal programme has enabled him to lift pre-grazing covers slightly and lengthen grazing rounds too.

“We were hit with clover root weevil in 2016 and we put on a lot of N to compensate for that.”

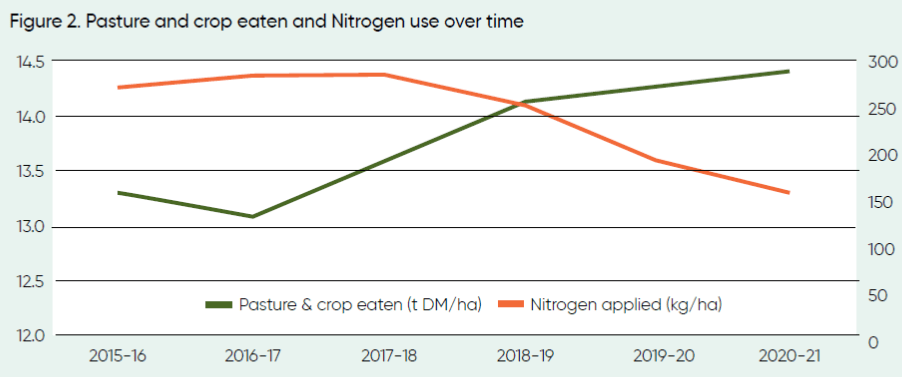

Applications got up to 283kg N/ha but as the clover root weevil populations dropped, likely due to the rise in the introduced parasitic wasp, and discussion over nitrogen loss reductions came to the fore, Tom began dropping urea application rates. In 2019 Tom decided to make a significant drop in urea use.

“We made a big cut in one hit and took out 66kg/ha that year – and yes the farm really felt that.

“Looking back, I would have done it over two seasons not just one because we just didn’t get the growth further into the season and we ended up using more palm kernel to compensate – so it cost us.”

The following season pasture production began to recover, and clover began to increase in the pasture.

Tom says cutting N use has been more about reducing the number of applications than rate per application.

“We went from following the cows every grazing round with an application of urea to putting it on monthly and we’ve cut two to three applications out that way.

“We cut the August application and we never did put it on in May.

“I did try cutting the January application out but that bit us too, so we’ve put that back in.”

Every paddock is below the 190kg N/ha cap and the average for the farm over the whole season is back at 155kg/ha.

He uses N-Protect to limit any losses of N to the atmosphere and the farm team has been “very focused” on good pasture management. They’ve also used gibberellic acid in the form of ProGibb.

The naturally occurring compound helps elongate cells and promotes growth in the grass.

Tom applies it over spring from mid- September with about 17kg N/ha and says he definitely sees a pasture growth boost three weeks post application that has helped him over the poor springs of the last two seasons.

Last season they invested in Allflex collars and are totally depending on them for identifying cows for mating.

The farm has always had a high six-week in-calf rate and low empty rate compared with regional performance.

“I’m very happy with how things are tracking – the return rate is putting us on track to get the in-calf rates we expect.”

This year they’ve gone to all artificial insemination thanks to the collars and their Protrack auto-drafting.

They’ve used short gestation length bulls in week four and Tom is expecting an even tighter calving next season.

They use the spring rotation planner to manage pasture through calving to balance date and get down to about 22 days round length.

Growing and utilising pasture is a top priority.

“The last two seasons have been really tough ones for growth but we’re still hitting that 14 plus tonnes drymatter harvested/ha.

“Hopefully we’ll do it again this year, but it’s been a really slow-growth spring and then all of a sudden a bit of rain and heat and the grass around the district pretty much ran to seed all at the same time.

“In retrospect though, when we look back at those high N use years, we were probably wasting nitrogen and wasting some feed too.”

The sudden cut exposed “the addiction” both for him and the pasture.

“We got into a system and way of thinking that meant it was just part of the programme and I think the pasture was used to it too.

“Clover is coming back now and we’ve adjusted the fertiliser programme to support it with a bit more potassium and trace elements.

“It’s definitely possible to get nitrogen losses down but you need to use a number of levers.

In a lot of cases those levers can have a win:win outcome – such as a shift to more precise spray irrigation giving the ability to grow more grass.

There’s also a greenhouse gas benefit to limiting nitrogen applications, balancing stocking rate and lowering feed inputs – both from a nitrous oxide and methane emissions perspective.

“We’ll keep looking to science for the answers – it has to be proven and it can’t come at a big cost to profitability.”