Words by: Anne Lee

Lincoln University PhD student Anita Fleming is warning more work needs to be done on how to safely feed fodder beet to lactating dairy cows and is suggesting farmers may have to feed smaller amounts more frequently to avoid animal health problems.

The recommendation stems from her three-year PhD study that included experiments with lactating cows in spring on the university’s research dairy farm.

Her PhD, which also included modelling, looked in detail at the effect on the rumen, the impact on the animal and the herd and analysed the farm system in terms of profit and risk. She’s concerned that despite using best practice transitioning methods two of the eight cows (25%) used in her onfarm experiment developed sub-acute ruminal acidosis (SARA), even at small levels of fodder beet feeding.

Her findings mirror those of DairyNZ’s Garry Waghorn and AgResearch’s David Pacheco. The experiment was published in the scientific journal Animals earlier this year. Despite the small number of animals involved Anita says the experimental design was robust enough to back up her assertion that 25% of cows in a herd could be at risk of SARA.

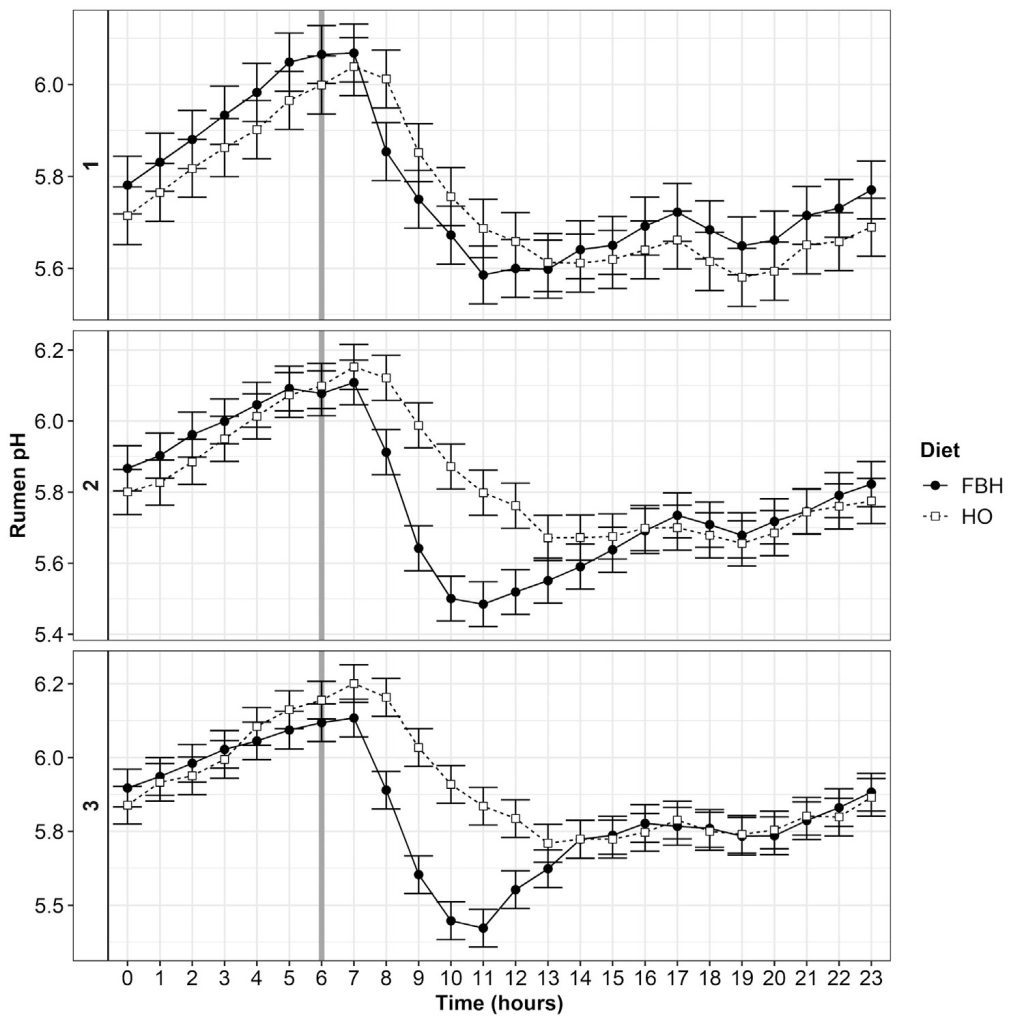

“We found that despite using the recommended ‘gold standard of transition’ – increasing the amount of fodder beet fed each day by 0.5kg drymatter (DM)/ cow/day, feeding them after morning milking and leaving them for up to two hours to ensure they had fully eaten their individual allocation, 25% of the animals still developed SARA. The cows were fed individually on harvested fodder beet with the leaf removed and were held at the covered yard area until they had eaten their allocations. SARA is characterised by the accumulation of volatile fatty acids (VFA) which reduce rumen pH. A pH less than 5.8 for more than three hours is defined as marginal SARA while a pH of less than 5.6 for more than three hours is defined as severe SARA.

In Anita’s study four cows were fed fodder beet while the other four were fed on pasture only for 20 days with rumen, blood and milk sampling carried out over the period. They then had a five-day “washout” period and the animals were swapped over and the experiment carried out again with cows that had been fed pasture transitioned on to fodder beet and those that had been fed fodder beet plus pasture in the first period fed pasture only.

The pasture-only cows were fed 19kg DM/day high quality ryegrass and white clover pasture allocated to each animal in an individual strip while the fodder beet cows were offered pasture in the same way and at the same pasture allocation but were supplemented with up to 6kg DM/cow/ day of fodder beet, with that upper limit reached following a transitioning process.

Anita found that one cow in the first period developed SARA on day 10 of adaptation to the fodder beet with her pH dropping below 5.5 for four hours.

Her allocation was reduced to 3kg DM/day and she was maintained at that until the end of the first period of the experiment. Another cow also developed SARA towards the end of the transition period with a pH of less than 5.5 for between 110 minutes and 190 minutes per day. Her allocation was also reduced but neither cow was removed from the study because pH stabilised without intervention, which is a defining characteristic of SARA.

Anita collected milk samples, blood samples, rumen content samples and measured rumen pH every 10 minutes using a wireless bolus in the rumen. She analysed amino acids and non-esterified fatty acid (NEFA) in blood, milk urea nitrogen (MUN), milk yield, fat, protein and lactose and milk fatty acid profiles, rumen pH, VFA, ammonia and L-lactate in rumen samples.

She also analysed both the fodder beet and pasture quality information including metabolisable energy (ME), neutral detergent fibre (NDF), acid detergent fibre (ADF), crude protein, organic matter and water soluble carbohydrate (WSC).

The continuous rumen pH measurement showed pH dropping after cows ate fodder beet but it also showed pHs dropped in cows after grazing pasture after the morning milking. NDF of the spring pasture was low at 36-41% and may be behind the drops in pH for pasture fed cows. The fodder beet had an even lower NDF at 13-14%.

The low NDF and high digestibility of fodder beet bulbs does not appear to complement the low NDF content of herbage, particularly after calving when the risk of SARA is higher, Anita says.

While analysis of all the data she collected on rumen, milk, blood and feed chemistry shows a complex story, she believes it supports her conclusion that fodder beet bulbs isn’t a good supplement for cows post calving.

“At an individual cow level, you may be able to manage her to minimise the effects.

“But even then, you can still run the risk of developing SARA as the experiments and modelling showed.

“So I’m worried for farmers as at a herd level there’s going to be a greater than 25% incidence of SARA, and probably more cows that are at serious risk from its longer term effects.

“SARA is sub-clinical so you can’t see it.

“When we carried out the experiment at LURDF each cow was given an individual allocation and held separately.

“It took up to two hours for them to get through their full fodder beet allocation when they had no competition and still, we had cows getting SARA.

“If they’re competing with each other in a herd situation competition is going to change their intake behaviour.

“Cows have nutritional wisdom and given the opportunity I think they slow down their intake to help lower the VFA produced in the rumen that leads to a drop in pH.

“In a herd feeding situation there’s competition and they stop listening to that post-ingestive feedback,” she says.

Anita’s results from her modelling study were also published in the Journal of Agricultural Science in July.

That study used the MINDY model, developed by Dr Pablo Gregorini when he was at DairyNZ – he’s now Professor of Livestock Production at Lincoln University and has been Anita’s supervisor for her PhD. Anita simulated 90 dietary treatments for a cow in early lactation using the model with variations of fodder beet allowance, timing of allocation and pasture allowance.

Fodder beet allowance included 0, 2, 4 and 7kg DM/cow/day with pasture allowances including 10.5, 16.1 and 28kg DM/day. The pasture was offered with fodder beet in the morning or afternoon or split between two equal allowances following morning and afternoon milking.

The fodder beet was offered in the same way. Anita says MINDY can determine the effects of the different feeding regimes on multiple animal outputs including rumen fermentation products such as VFA.

It can also determine the level of discomfort the animal is experiencing.

Anita says MINDY found that milk production was similar when the diet was 0 and 2kg DM/cow/day of fodder beet but dropped by 4 and 16% when fodder beet increased to 4 and 7kg DM/cow/day.

MINDY predicted SARA would result at the 7kg DM/cow/day fodder beet level and that rumen pH would be less than 5.6 for 160 and 90 minutes per day at 7 and 4 kg DM/cow/day fodder beet.

Further analysis found the best compromise between high milk production and low discomfort was achieved by splitting the 2kgDM/cow/day fodder beet offering into two equal meals per day fed with 28kg DM/cow/day of pasture.

“At a farm level that’s just not really practical,” she says.

She ultimately concluded that because of the low milk response and high risk of acidosis fodder beet is a poor supplement for lactating dairy cows.

To round out her PhD Anita carried out a whole farm modelling exercise, using DairyNZ’s Whole Farm Modelling with that study accepted for publication in the scientific journal Agricultural Systems. She looked at two locations – Waikato dryland and Canterbury irrigated with the farms in the model loosely based on Scott Farm in Waikato of the Lincoln University Dairy Farm (LUDF) in Canterbury.

She compared four different scenarios to support milk production in late and early lactation:

- using fodder beet on the milking platform,

- growing maize on the milking platform to produce maize silage,

- buying in maize silage as a supplement (base scenario),

- growing fodder beet on the platform but having an outbreak of acute (1% stock death) and sub-acute ruminal acidosis.

The maize was sown in November and harvested in February or March and was then able to be fed out in autumn and spring.

Fodder beet was sown in October, grazed in autumn and the residual crop harvested and fed out to cows in spring.

The financial results showed that the time ground was out of the grazing round had a bigger effect even than yield.

“We looked at how much milk the cows will produce based on the average BW cow and what that would mean to the farm’s bottom line in terms of economic farm surplus (EFS) as well as the risk exposure in terms of return on asset.”

She used 300 different combinations of milk price, supplement price, climate, land appreciation and interest rate.

She found the EFS was up 5.8% when maize was grown on the platform compared with the base scenario for both Canterbury and Waikato. That was due to increased milk production, lower feed expenses and shorter crop rotation. Growing fodder beet increased the EFS by 4.8% in Canterbury compared with the base scenario in Canterbury but was similar to the base scenario in Waikato. Anita says there was limited advantage to growing fodder beet in Waikato dryland conditions because the length of time the crop was out reduced pasture production. The ruminal acidosis scenario saw a 6.5% reduction in EFS in the Canterbury situation and 7.1% in Waikato compared with the base scenario. Anita sys the model predictions showed a greater advantage for maize silage grown on the farm than imported maize silage or growing fodder beet on the platform as an autumn and spring supplement. It better complemented New Zealand’s pasture-based system by improving milk production, profit and reduced business risk due to a combination of shorter crop sequence and greater feeding flexibility compared to fodder beet, she says.

Even a relatively minor outbreak of ruminal acidosis caused a substantial decline in income.

“There appears to be little advantage and high levels of risk associated with growing and feeding fodder beet on the platform to support lactation,” she says.