Keri Johnston

Changes to the way we manage freshwater have been proposed in a consultation package released by the Government on September 5, with differing reactions from the sector and advocacy groups.

This is my take on the package and what it means for farmers.

There are two main objectives:

- To ensure no further degradation of waterways and start making immediate improvements so that water quality is improving within five years; and

- To reverse past damage and bring waterways and ecosystems to a healthy state within a generation.

It is important to note that the package does not address allocation issues (quantity or quality), or iwi rights and interests – this will come later. So, what is in the package?

ACCELERATED PLANNING PROCESS

The rule making framework is too slow and doesn’t always work well. Therefore, amendments to the Resource Management Act (RMA) are proposed.

Plan hearings will be heard by an advisory panel consisting of government appointees, regional council appointees and iwi representation.

Regional councils will be required to have plans in place by 2025 which give effect to the new National Policy Statement for Freshwater Management (NPSFM). There will be restricted avenues for appeal.

Regional councils will be required to have plans in place by 2025 which give effect to the new National Policy Statement for Freshwater Management (NPSFM). There will be restricted avenues for appeal.

There is little detail on this point but think how it has been for Canterbury under the ECan Act where appeals have been restricted to points of law only. As frustrating as this has been where there has been a fundamental technical faux pas, it has sped up the time at which the plans have been put in place as it’s meant they haven’t been tied up in the Environment Court for years.

Under the current NPSFM, councils had until 2030 to give effect to it. Many councils have been proactive and done this (Canterbury for example), but many areas still have no proper plan in place, and while this is the case, further degradation of waterways is still able to occur (not intended, but an unforeseen outcome).

Bringing the timeframe forward by five years is not a bad thing for those areas that have done nothing to date (if they had got on to it sooner, perhaps the Government wouldn’t have felt the need to deliver this package!) It will however put a huge amount of pressure on human resources, and money to deliver by this date.

THE NPSFM

The Government is “raising the bar” when it comes to ecosystem health. The proposed NPSFM brings in the concept of Te Mana o te Wai, or “the mana of the water”. This refers to the importance of prioritising the health and wellbeing of water before providing for human needs and wants.

The criteria when making decisions that impact on waterways have been extended to include aquatic life, habitat, water quality, quantity and ecological processes.

Changes are also proposed to strengthen the priority given to tangata whenua values, and these must be given the same priority as ecosystem health and human health for recreation in regional plans. Mahinga kai (traditional food, tools, or resources; the places they are found; and the act of gathering or catching them) will be provided for in identified waterbodies and all freshwater management units.

The NPSFM also brings in a number of attributes to be monitored and maintained or improved as indicators of ecosystem health. These are dissolved inorganic nitrogen (DIN), dissolved reactive phosphorus (DRP), sediment, fish and macroinvertebrate numbers, lake macrophytes (the amount of native or invasive plants), river ecosystem metabolism and dissolved oxygen in rivers and lakes.

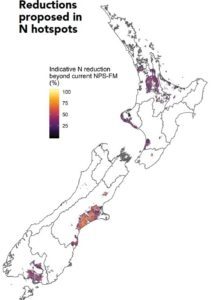

I have seen a lot of press around the DIN attribute. The proposed national bottom line for DIN is 1mg/litre (five-year median). Many areas are already well within that level. However, in some areas (about 15% of NZ) this limit is being breached, and in some areas, by quite a lot (more than 10mg/l). In those areas meeting a bottom line of 1mg/l will be tough.

The Government has made it very clear that the addition of the DIN attribute was very late in the piece, and no impact assessment has been able to be done. Therefore, they are very open to feedback.

Ponder this:

First, there are no timeframes in the NPSFM for meeting bottom lines. An appropriate timeframe is negotiated with the regional council and other parties involved in the planning process. I know from my own experience that negotiating timeframes is not as easy as it sounds, but the Government has made it very clear this is a generational package, and there is no expectation bottom lines are met straight away.

The second point is more of a question. Do you set bottom lines for the majority or the exceptions? I’m not 100% sure of the answer, but any bottom line set must have sound scientific justification, and that potentially will be a stretch. Setting a bottom line that is “easy” will be seen as a cop out, and as an industry, we have to be seen to be continually improving.

The Government has also identified a number of “at risk” catchments which must reduce nitrogen leaching.

There are three options proposed to do this – highest-leaching farms over a certain threshold need to reduce leaching as modelled by Overseer, national cap on the use of nitrogen fertiliser, or the use of Farm Environment Plans (FEPs) to plan immediate reductions. A national cap on nitrogen fertiliser isn’t going to achieve anything, so one of the other options or a combination will be the answer.

HOLDING THE LINE

Restrictions on agricultural intensification are also proposed as part of the package. This means that from July 2020, any area of more than 10 hectares that wants to undertake an activity such as irrigation development, increase in winter grazing, or change in land use, will require a consent.

Consent can only be granted where it can be demonstrated that there will be no increase in pollution caused by the activity above a property’s 2013-2018 baseline average. These restrictions will only apply until councils have introduced their new plans (which must be in place by 2025).

It is unclear whether these provisions apply in areas such as Canterbury where “hold the line” plans are already in place and in many parts of the region, require nutrient reductions to meet environmental outcomes.

At-risk catchments:

- Northland: Waipao Stream (in the Wairoa River catchment)

- Bay of Plenty: Upper Rangitaiki River (upstream of Otangimoana River confluence)

- Waikato: Piako River, Waihou River

- Hawke’s Bay: Taharua River (in the Mohaka River catchment)

- Taranaki: Waingongoro River

- Wellington: Parkvale Stream (in the Ruamahanga River catchment)

- Tasman region: Motupipi River

- Southland: Mataura River, Oreti River, Waimatuku Stream, Aparima River, Waihopai River.

This article is free to view because it is a topic of high importance. This article was published in Dairy Exporter magazine. For less than $10/month, you can receive this detailed information to help improve performance within your business. nzfarmlife.co.nz/

Supporting New Zealand agri-journalism.