By Joe McGrath

It’s a commonly held view that calving cows in autumn is much easier than the more common spring (it’s really winter) calving. But why so? Or, more importantly, is it, in fact, easier – or does it just seem that way because the sun is out, the days are longer and it’s not freezing cold?

It’s fair to say there has been no robust statistical analysis performed on this conundrum so I can’t categorically state autumn is easier than spring. However, when I analyse the nutrition/environmental factors involved it’s true that autumn calving should be much easier for the cow.

There are two main reasons for this. The first is because the cow is coming off the back of summer and should be at the peak of her natural annual vitamin D cycle.

This ensures there are no deficiencies impeding her ability to mobilise calcium at calving. The second main reason is that the grass is usually not nearly conducive to the typical mineral deficiencies that we see in spring.

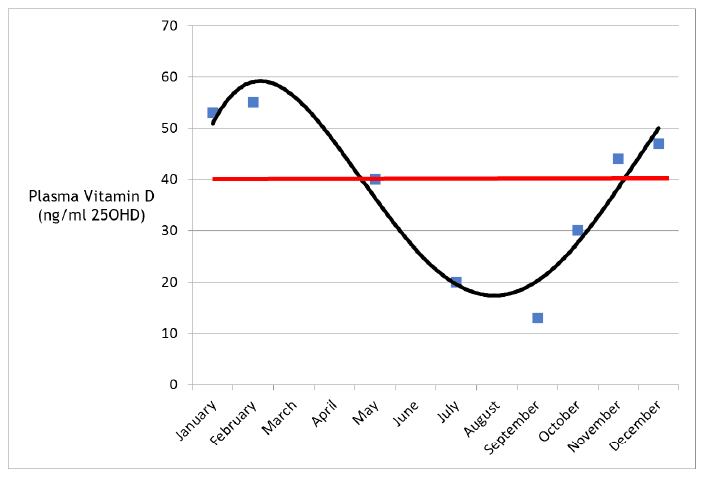

To elaborate, Vitamin D status is variable during the year, with the peak being in late summer and the trough in late winter early spring (see Figure 1).

This is important for cows that live outdoors. While the late winter level of Vitamin D is not clinically deficient, it does mean the cow has less resilience against other nutrient imbalances at calving time.

Cows that live in TMR barns have their levels of Vitamin D kept at the red line on the graph. That’s because nutritionists understand the key role that Vitamin D plays in calcium, phosphorus and magnesium control.

In autumn we have this Vitamin D “tool” working in our favour. Does that mean we don’t need to monitor what goes in our transition cows’ diet – no. However, it does mean she has a greater chance of dealing with dietary mistakes.

The second variable is linked to the first. The amount of nutrient imbalance in grass is usually less in autumn than in spring. The primary nutrients of concern are N, P, K, S, Mg and sugar.

Generally, problem pastures or highly imbalanced pastures are due to poor soil nutrient profiles. In this case, when I mean poor I don’t mean under fertilised; I mean over fertilised. In many cases because we’re pushing too hard for the next tonne of drymatter growth without considering who the customer is (the cow!).

Autumn grass tends to have more fibre, hence more calcium and less phosphorus, sulphur and most importantly potassium.

That means the magnesium is more available, therefore less chance of tetany, greater calcium intake and, importantly with more vitamin D in the system, a greater chance to utilise it and calve happy and healthily.

So are there any negatives to calving in autumn? Autumn often means drought, so less carotenoids and alpha-tocopherols coming through the grass.

These are important for immunity and reproduction. Also nitrates can be an issue in the grass, but, in general these two negatives are less common than the positives, so are outweighed. For a high-producing herd however they should certainly be taken into account.

I think we can safely say from a nutritional perspective, on most farms in most years and under the same management, an autumn calving will generate considerably less milk fever than winter calving.

The question is, are you able to handle all the other challenges associated with autumn calving on your farm?

- Dr Joe McGrath is Sollus Head Nutritionist.