Peter Flannery

Is your business generating enough surplus cash after all expenses including tax, personal drawings and capital expenditure, to be able to repay 3% of your total debt annually? The Banking Industry has changed. Depending on the strength of your Business, this may limit your access to borrowed capital. To understand the “why” and the potential impact on your Business, we need to look back in time.

Prior to 1984, the banking sector in New Zealand was heavily regulated. With such heavy regulation there was no incentive for banks to compete for business. It was the days when bank managers sat in their offices, behind oak doors and oak desks, heavily guarded by sub managers and junior staff. Following deregulation in 1984, it took a further six years before competition started in earnest.

Then followed a period of 20 years or so when competition became so fierce, the pendulum of power swung back to the client. Banks competed on price, quality and mostly importantly relationships. It was the start of relationship banking. Normal lending criteria was replaced with lending guidelines. Competition was driven by the seemingly endless and ever cheaper funding lines banks had access to offshore. Growth in lending was seen as a good way to increase shareholder returns.

As land values increased, security margins improved, which gave farming businesses greater borrowing capacity which fuelled land values which gave farming businesses more borrowing power and on it went. Yes, commodity prices and on farm productivity were lifting, which also transferred into increased land values, but those two factors cannot explain a 15-fold increase (anecdotally) in land values over 20 years. Over the same period, farm debt increased 11.5-fold.

Rural managers were employed as credit assessors and were also tasked with growing their lending book. With relationship banking rural managers turned to becoming client advocates and helped clients prepare budgets and lending proposals. Many clients started to see their banker as their most trusted adviser, however, the rural manager was employed by the bank. So, lines of responsibility got blurred. Not deliberately, it just evolved that way. Whilst I would like to think everyone acted with integrity, a definite conflict of interest existed. Banks had plenty of money to lend and they were lending it and farmers were borrowing it.

Then it changed. In 2008, the global financial crisis (GFC) hit. Internationally, loan payment defaults soared, banks started failing or at least posting massive loan write offs. The trust went out of the banking industry and banks stopped lending to each other. Suddenly and unexpectedly, access to funding dried up.

While NZ came through this period relatively unscathed, 10 years on, the impacts are now only really starting to be felt as bank regulators force banks to hold significantly more capital on their balance sheets and have imposed significant restrictions on offshore funding.

The Reserve Bank is not done yet, proposing banks double the capital they are holding. Furthermore, a Responsible Lending Code places the emphasis on the client to provide the supporting information for a loan proposal and the bank’s role is to assess it. The client must show capability to be able to repay the loan, and as a result banks are increasingly requesting contractual principal repayments.

With the rural sector over-indebted, banks having to hold more capital, and restrictions on where banks can source their funding, banks will start to target their capital to where they can get the best return. That will have a significant impact on banks and client alike. How each respond to the new norm will set them apart.

So, what does all of this mean?

Nearly 30 years of strong bank competition has reduced. Most banks are now quite content with their market share. A generation of farmers have either grown up with or have become used to an environment of relatively easy access to bank borrowing. This has created expectations that are now no longer being met.

Banks no longer have what was virtually unlimited access to ever cheaper funding. They instead need to source 80% of their funding from domestic based depositors. As interest rates drop, it is going to become harder to attract and retain depositors, further tightening funding.

The RBNZ is strongly of the view that the rural market is over-indebted. With the Responsible Lending Code now part of the Credit Contracts Act the RBNZ is keeping a close eye on rural lenders. Banks are increasingly requiring clients to enter into contractual principal repayments. Over the last 30 years, a bank was happy to allow clients to be on interest only. The bank wanted to know the client could repay but didn’t need to repay. Now they do and are increasingly requesting contractual principal repayments.

Furthermore, the client needs to provide the information to allow the bank to assess the ability to repay. Bankers are increasingly no longer able to gather that information on behalf of the client. It needs to be provided. If a client cannot trade profitably enough to repay debt from cashflow, banks are now asking their clients for their plan on how they intend to rectify the situation.

Banks have already had to increase the amount of capital they hold, and this could potentially double. Furthermore, and this has already happened, poorer quality lending requires an exponentially higher capital allocation than quality loans. Therefore, to provide a bank with the same return on their capital, the interest margin will increase as quality decreases.

In a low interest rate environment, an increased margin makes up a significant percentage increase in debt servicing.

With increased level of capital being held, and a reduction in the supply of funding, banks will be more circumspect over which industries they will lend into. Just like the pre-1984 era when the Government had favoured industries for banks to lend into, banks will have their own favoured industries.

Farming asset values are dropping for a variety of reasons. The new banking environment will be one of those reasons. This is a double-edged sword. It reduces the borrowing capability of all businesses and as security values (LVRs) increase, banks will be required to allocate more capital against individual loans. Thankfully current farming profitability is good, but as every farmer knows, it is not always like that.

With the introduction of the Responsible Lending Code, banks are now quite rigidly sticking to their lending criteria. Through the boom period banks went outside of their lending criteria so frequently it became the norm. Criteria turned into guidelines. That has now come full circle, to the extent that criteria is now viewed in many instances as minimum criteria. Not only does every box need to be ticked, they need to be big ticks.

Like it or not, banks are having to bow to the increased regulatory requirements and increased scrutiny from not only the RBNZ but also their shareholders. It’s easy being a good banker when the going is easy, it is altogether different when it is not.

How banks perform under this “new” regime will set them apart from each other. Every bank will be operating under the same regulatory requirements, and it is how they administer and operate within those requirements that will set them apart. More than ever it is important bankers adhere to some strong relationship values. Among those values will be:

- Empathy

- Integrity

- Patience

How individual farming businesses perform in the “new” norm will also set them apart. They will need to have a very clear business strategy. They will need to have strong clarity around their business’s:

- Purpose

- Values

- Vision

- Plan to achieve the vision.

For many, capital gain, and therefore access to increased borrowing has masked inconsistent profitability. That option is less likely to exist now, than in the past They will need to be less reliant on their banker (but still maintain a strong relationship) and have a greater focus on ensuring their business is operating at the optimum level. Increasing productivity and efficiency will be key (this should not be confused with increasing production, which is a different thing altogether).

Farmers are a tenacious and resilient bunch. As always, I am sure the good ones will flourish, the average will be fine, and the tail end will drop off. Nothing has changed there, but only if they understand and adapt to the new norm.

The challenge is, be good at what you do, understand and adapt to the new norm and most importantly build financial buffers.

Banking – A New Norm?

Pre 1990 and the Rule of 3-6-3

In 1990 a farmer asked me “Have you got plenty of money to lend?” I was working for the Rural Bank and was just starting my 21-year banking career. I thought, what a stupid bloody question. The Rural Bank had recently been purchased by Fletcher Challenge, having previously been a State-Owned Enterprise. The bank held just under 50% of the onfarm debt. Every other bank wanted a share of it, and we were determined to retain it.

So of course, we had plenty of money to lend. It took me nearly 20 years to realise it wasn’t a “stupid bloody question”. It was a question born out of the then recent past, and now 10 years on from the GFC, it is a question which, over the coming years, may well become more relevant.

Prior to 1984, banking was heavily regulated. It was a banking world that would seem so foreign today. It seems hard to believe now, and only those with a few more grey hairs than I, and I’m starting to get a few, will really remember or appreciate what it was like.

Prior to 1984, the Government pretty much regulated everything. Transport, exports, foreign exchange and certainly banking and capital allocation.

During this period, the Government at varying times and to varying degrees regulated the amount banks could lend and had a heavy hand in setting deposit and lending interest rates. The five trading banks were more heavily regulated than “non-financial institutions” such as savings banks and finance companies. Banks at one time had no ability to source overseas funds, and their lending was confined to industries favoured by the Government.

Non-financial institutions were able to more easily compete for deposit funds and as a result, trading banks had limited access to capital. Over time the Government realised this created an unfair playing field, and rather than easing the restrictions on the trading banks, they increased the restrictions on non-financial institutions.

The Rural Bank, which was a Government agency, was created to provide funding for the various aspects of the agricultural sector, including various Government schemes such as Land Development Encouragement Loans and Livestock Incentive schemes. In essence, it was an administrator and allocator of Government policy and capital. It was almost entirely funded by the Government and was focused on:

- Helping sharemilkers get a start,

- Settling young farmers on to the land and,

- Onfarm development and infrastructure for established farmers.

It certainly wasn’t set up to allow for growth and expansion of farming businesses, nor did it provide seasonal overdraft facilities. There was a saying within the Bank, “we’re for the needy, not the greedy.”

Once the Bank had lent its annual allocation of capital, new loans had to wait for the next financial year.

There was no need for the Rural Bank to respond quickly to loan applications. They had a captive market and a limited source of funds, so there was no need to make any hasty or rash decisions.

Likewise, the same thing was happening at the Trading Banks, although to a lesser extent. There was absolutely no need to compete on any level, whether that be on interest rates, client service or market share. Bank Managers sat behind big oak desks, in an office guarded by big oak doors and a small army of minions who would filter out the chaff before anyone got to see the manager. They wielded huge power with both customer and staff alike.

As a result, access to capital was tight. It was not uncommon for farmers to have up to four mortgages from four different lenders.

The most common scenario would be for the Rural Bank to have first mortgage to secure term lending. Thereafter it was a battle to fight for what was left. A Trading Bank would most likely be in the mix somewhere, to secure seasonal funding. Stock firms, Solicitor Trustee Account mortgages, Insurance Company mortgages and Vendor or Family mortgages would also likely be in the mix.

One day in the 1990s, an aging banker who had a solid career with the National Bank was telling me a few stories. With a nostalgic look in his eye he talked of the 3-6-3 rule. They got the deposits in at 3%, lent it out at 6% and was on the golf course by 3.

However, 1984 ushered in a new Labour Government lead by David Lange, ably assisted by Roger Douglas. In a very un-Labour like way, they decided it was time for a change, and Roger Douglas went to work with a vigour that has seldom been seen before or since by a politician.

Everyone knows the havoc he created in the farming sector. He removed farming subsidies and rewrote the workings of the Rural Bank. Product prices plummeted and interest rates soared to mid 20%. There were plenty of casualties, and I often wonder how anyone survived, but they did. Evidence of the tenacity of the farming community.

However, while that remains fresh in the minds of many, they were only some of the reforms. Foreign exchange markets were deregulated, the NZ dollar was floated, the transport sector was also deregulated. Douglas had plenty else in store, but Lange stepped in and said, “I think it’s time we stopped and had a cup of tea.”.

Amoung the furore of the change to a free market economy the deregulation of the banking industry largely went unnoticed. Following 1984, banks were given access to foreign capital, could set their own interest rates are were free to lend to which ever sector they so choose. They became masters of their own destiny and were free to compete.

So, the banking doors of competition were flung wide open and… nothing happened. Well not in the agriculture sector anyway.

Banks couldn’t see any great future in rural lending. Profitability and equity was non-existent, land and stock values were down. With no profitability and a lack of security farming didn’t make for an overly attractive lending proposition. Farming was a sunset industry, or so it seemed, if you listened to anyone other than a farmer.

For banks and financiers there was enough other stuff to be getting on with, including:

- Commercial property prices increased by 150% from 1984–87, thereby an attractive place to lend money into.

- The share market trebled in value over the same time. Again, another great place to pour money into until that is, the share market crash of October 1987.

- The BNZ which was largely Government owned, had to be bailed out twice in the 1980s, before finally being sold to NAB (National Australia Bank)

- Rural Lending Discounting happened. A scheme where, on a case by case basis, individual farmers and their lenders meet to restructure loans. This involved the write down, particularly of Rural Bank debt, and subsequent Mortgagees agreeing not to take action to recover their lending for a period of time. With the write down of loans, negative equity was turned to positive equity, giving the Seasonal Financier security and confidence to continue to provide seasonal funding. The downside for the farmer was for Rural Bank concessionary interest rates of around 7.5% to be increased to commercial rates.

So, there was a bit going on and with the entrenched conservative nature of bankers, entering into a bright new and brave world, money was to be made by lending into any industry other than farming.

It is little wonder then that in 1990, a progressive farmer would be interested to know if the bank had plenty of money to lend.

1990 to 2008 – The Arrival of Relationship Banking

However, by around 1990 that had started to change. The Government sold off the Rural Bank to Fletcher Challenge in 1989. The carnage of the 1980s was starting to come to an end and the dust was settling. Bankers slowly awoke to the largely untapped rural lending market.

It was around this time that the Trading Banks started employing specialised rural lenders. The five trading banks all started shoulder-tapping well-regarded Rural Bank staff. (and yes, for the record, I was one of them but stayed with the Rural/National Bank)

In 1990, my memory tells me the Rural Bank loan portfolio was $2.0 billion and accounted for close to 50% of farm debt. Therefore, total farm debt of $4.0b. According to Reserve Bank figures, total farm debt in New Zealand is now $62.8b, a staggering 15-fold increase over 29 years.

Why has it increased so much? Virtually unlimited bank access to funding, mostly from offshore. With a seemingly unlimited supply of funds and an untapped rural market it was time to compete. One of the first out of the blocks was the National Bank. In early 1990 they introduced a market leading five-year fixed rate loan at 14.75%.

But lending growth for them and the other banks was slow.

When Fletcher Challenge decided rural banking wasn’t for them, they put the Rural Bank up for sale and in 1994 National Bank purchased it. At the same time, ASB left its Auckland roots and aggressively entered the rural banking market, and Westpac and BNZ soon followed. ANZ dabbled but made little ground.

PIBA (Primary Bank of Australia), the Australian version of the Rural Bank, opened up shop in 1989 and made minimal impact. They then morphed into Rabo Bank when the Australian parent was bought by them. Rabo Bank later purchased Wrightson Famers Finance and have since gone on to become a significant rural lender.

There were several ways to compete. Lower interest rates and lower credit quality standards were two ways to grow market share. However, the most effective long-term approach was to deliver a standard of client service and build strong relationships that no one could touch. It was the start of what was called Relationship Banking. It was hard to take good business off good bankers. As a result, Rural Managers became very close to their clients and almost unwittingly became advocates more so than risk assessors. In fact, as we progressed into the 2000s, we measured client satisfaction levels, and strove to be the clients’ “most-trusted adviser”.

All the while with almost unlimited access to funds, farming businesses grew, and with it, so did bank portfolios and land values. What was considered to be a tight deal at the time, turned into a sweet deal two years later as ever-increasing land values masked inconsistent profitability and kept adding securable value to loans.

If my memory serves me correctly, land in Central Southland that sold for $2500/hectare in 1990, sold again in 2008 for $38,000/ha. It was not uncommon to bank someone into a new property with less than 35% equity on completion. Two years later, the equity position would have improved to well over 50%.

Timeframes for getting loans approved shortened, and if you wouldn’t do it, someone else would. Not that we always said Yes. Every now and then someone of high importance and ego would try to hold you over a barrel. It took courage to say No, but when you did, it was more often than not, the right call. Someone else would generally always do it though. There are some high-profile cases where ego and importance wasn’t matched by onfarm ability, with the inevitable result. It was the eyes bigger than belly syndrome.

I shouldn’t paint the picture that all lending was poor. That definitely was not the case. The vast majority of it was fine and some very good operators made some very good business decisions and grew their business for the benefit of themselves and their bank. Not only that, certainly from my own perspective, some lasting relationships were forged with some truly wonderful people.

Competition tightened up time frames to get credit approval and the closer we got to 2008, the worse it became. In some instances, we had 24 – 48 hours to get approval. It wasn’t so much that our clients were being unreasonable, it was the state of the land market. Properties were being bought and sold before they were advertised to the market. There was no time for due diligence on behalf of the buyer or the banker. Major investment decisions and major lending decisions made in the blink of an eye. When you consider most new lending proposals involved multi million dollars of asset, funded by multi-million dollars of new debt, 48 hours of due diligence is not prudent business practice.

However, when you build a strong relationship with a client, it is hard to disappoint them and say no, and as a result, their expectations of what we could do increased. One such case comes to mind. A dairy farming client of mine owned a 250ha dairy farm. An adjoining 100ha came on the market, to be auctioned in six weeks’ time. I rang my client and asked if he was interested, to which he replied, “no, it will be too expensive”.

Six weeks later, I was in the North Island doing a Bank promotional tour. I got off the plane in New Plymouth and I had a message on my phone to ring my client.

“Hello” he said. “That auction is today. Can I buy it?”

“You’re joking. You said you didn’t want it, and besides I’m in Taranaki. There is no way I can get a credit approval in time.”

“Can you try please.”

So, I quickly asked a few questions wrote down some brief notes. It was a tight deal and I was light on detail, however he had a good recent history of profitability and I knew he would do whatever he had to, to make it work. I rang my Credit Manager in Wellington. A half-hour discussion ensued. Between us we discussed the merits of the proposal. Finally, the real question came from my Credit Manager:

“Is he going to let you down?”

“No.”

“Are you going to let me down?”

“No.”

“Ring him back and tell him its approved and you can sort out the paperwork next week.”

“Thank you.” I said.

That turned out to be a good decision, and because he was good at what he does, his business went from strength to strength. For the client and the Bank, the benefit of a good relationship.

The problem this strong relationship caused was, clients became increasingly reliant on their Rural Manager. The Rural Manager was an employee of the bank, whose main role was to assess credit risk on behalf of the Bank. The Rural Manager was also expected to increase their lending portfolio.

The client would rely on budgets prepared by the Rural Manager, so in reality, it was the Bank’s budget, not the clients. The client’s risk assessment was based on whether the Rural Manager could get the loan approved. But a loan approval was based on how the Bank saw the risk for the Bank, and not necessarily the risk to the client.

While the two were very closely linked there is a difference. In many cases, the Rural Manager was the client’s most trusted adviser, and prepared the budgets and valuations upon which a client’s investment decision was made, and then went on to lend the client the money. Therefore, a definite conflict of interest existed, and whilst it was generally well managed and with integrity, it was a conflict of interest nonetheless.

It is difficult to know whether the exponential growth in lending was a supply or a demand-driven outcome. It’s a bit like trying to work out what came first, the chicken or the egg. I suspect it was an inevitable mix of both. Unfortunately, the banks and the clients walked hand in hand down the beach towards a brewing storm that unfortunately wasn’t forecast but with the benefit of hindsight was inevitable.

Recent experiences shape how we see the world. Nearly 20 years of lending conditions created by free market forces of supply and demand shaped everyone’s thinking. What we were experiencing became the norm and why should that change? It is only with hindsight we see the flaw in the plan.

By 2008, the last question on anyone’s mind was “have you got plenty of money to lend?”.

2008, the GFC and beyond and “Oh Shit”

In 2007, Fonterra’s milk price was $3.87. The following year it jumped to $7.79/kg milksolids (MS). This encouraged one last mad scramble for land and one last surge in bank lending. But things were slowly unwinding particularly in the United States. At this stage, the world was literally awash with funds, which had to find a home.

In the USin particular, this led to dodgy lending and creative accounting leading to easy credit, on the back of weak borrower and bank Balance Sheets. Banks bundled up loans and on-sold them to Investment Banks, other Banks and Superannuation companies, thereby cunningly avoiding Capital Adequacy ratios.

Because the loans were created through easy credit, they were not quality loans. They were less than prime. In fact, they were subprime. Inevitably then, the loan defaults started, and the chickens came home to roost. The biggest problem was, because the subprime loans had been bundled up and sold, no one new exactly where the loans originated from, so banks couldn’t get a handle on the size their impaired loans.

If you don’t understand any of that, you are not on your own. Alan Greenspan was the longest-serving chairman of the Federal Reserve in the United States and he has admitted he didn’t understand what really happened.

If you don’t understand any of that, you are not on your own. Alan Greenspan was the longest-serving chairman of the Federal Reserve in the United States and he has admitted he didn’t understand what really happened.

Banks and Investment Companies lend to other banks. It is this flow of funds that keeps the financial markets liquid and businesses operating. Without this flow of funds, credit freezes. This is what happened. No one knew where the subprime loans sat or to what degree. Banks started to fail, and no one knew which bank would be next. So, banks stopped lending to each other. The world was still awash with funds, but no one was prepared to lend them to anyone for fear of not getting them back.

Back in New Zealand, the National Bank treasurer put it to us this way. Pre GFC, they would open up their window on the top floor of the head office in Wellington and stick the fishing net out the window. They would pull it in, and it would be full to overflowing with funds, each time cheaper than the last. Once the GFC hit, they put the net out the window, and when they pulled it in, it was empty. Oh shit!! (or words to that effect). It was a mad scramble to the Northern Hemisphere to source funds. I know with the National Bank, they were able to source funds, but instead of being only 0.10% above wholesale rates, they had to pay a margin of around 6.0% above wholesale rates.

Businesses face many risks. The one that ultimately causes failure in any business is lack of liquidity. Banks used to be terrified of liquidity risk. Liquidity becomes an issue when a bank doesn’t have enough funding to either:

- Cover depositors withdrawing their cash from the bank or,

- Meet impending loan drawdown commitments.

When either of those two happen, the market loses confidence and you end up with a run on the bank. A small problem very quickly becomes a big problem.

Of course, with a world awash with funds, liquidity risk was well under control. But all of a sudden in 2008, it became very front of mind. The storm had arrived, and the golden weather was over.

How did banks respond? They scrambled for funds, almost at any price, and quickly turned their attention to liquidity. Within the National Bank, and seemingly overnight, the rules changed. No longer was it about credit, it was all about liquidity. Before a loan application could be submitted to credit, it had to first go to the funding committee. Will we have the funds available to be able to make the loan?

So, for 18 months the bank prioritised the use of their liquidity as follows:

- To meet the day to day overdraft requirements of existing clients.

- Fund known contingencies for existing clients, where they had no other option other than Bank funding.

- Sensible growth opportunities for existing clients.

- No funding to new clients.

To the average person walking down the street, all seemed calm and business as usual, but that was far from the reality. I know for many Rural Managers it was like being caught in the headlights. Not only was funding liquidity tight, but the banks’ cost of funding increased. Interest rate margins which had been in steady decline since 1990, suddenly jolted up. There were some difficult conversations to be had, particularly if an Interest Rate Swap was involved.

It was stressful for all concerned for 18 months. Tight liquidity, increasing margins, the swap saga and dropping commodity prices. But after that, things improved and commodity prices, particularly milk had a good run. For many, the GFC was just huff and puff and a big deal about nothing.

The Australian-owned banks and their NZ subsidiaries all came through pretty much unscathed, as did the European-based Rabo Bank. Many thought the impact of the GFC on their business was done and dusted.

But not all was calm in the halls of regulatory powers.

Central Banks around the world got a hell of a fright, and the Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ) was no different. The RBNZ started auditing the banks looking at the quality of their lending. And one of their conclusions?

“There seems to be an awful lot of farm debt, and we are not sure it is sustainable.” Some pretty hard questions were starting to be asked of bank executive and governors.

The first thing the RBNZ did, was to severely reduce banks’ access to offshore funding. Very quickly the RBNZ required banks to source at least 80% of the funding from domestic based depositors, rather than the

“on tap” offshore funding. This is to help isolate NZ from future international credit freezes.

Whilethis is a prudent move, it does start to limit funding lines. So, there isn’t as much money to lend as there used to be. I wouldn’t say there is a scarcity of supply, but there certainly isn’t an unlimited supply.

There is a city in Switzerland called Basel and it sits plonk in the middle of Europe. It is home to the Basel Committee of Bank Supervision. It is a committee made up of representatives from 45 countries’ central

banks. Their purpose is to improve the quality of banking supervision worldwide. Whilst they have no legislative power, they do make a series of recommendations or Accords.

Banking stability, and trust within the industry is vital to ensure banks have confidence to lend to each other.

It is what creates liquidity. How do you create stability? By ensuring banks don’t fail. How do you do that?

The same as any other business. They need a strong balance sheet. To prevent failure, banks need enough capital of their own, to be able to handle financial shocks, such as the GFC. The measure of capital a bank

should hold is known as the Capital Adequacy Ratio. Remember that, because that is going to become increasingly important to understand.

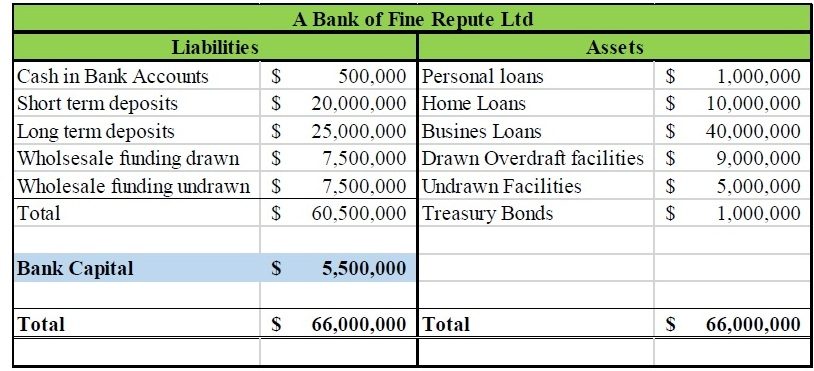

So, what does this mean? Like any business, banks have assets and liabilities. The difference between the two is the equity within the business, or in other words capital. A bank’s assets could be made up of any of the following for example:

- Loans made to customers, whether that be unsecured personal loans, housing loans, commercial loans or wholesale loans to other banks.

- Business overdrafts, both drawn and undrawn.

- Cash reserves sitting in the vault.

- Treasury or Government Bonds.

A bank’s liabilities may be made up of the following:

- Credit funds in bank accounts.

- Short term deposits from customers.

- Longer term deposits from customers.

- Wholesale funding lines from other banks.

A very simplified bank balance sheet may look like the table above. In this example bank capital of $5.5m represents 8.3% of total assets. The reason a bank needs a minimum level of capital, is to provide protection to depositors and hence trust, because banking is built on trust. If a bank makes a series of poor lending decisions and has to write off loans, it impacts first on the bank’s own capital, rather than depositors taking a hit. And that builds trust and without trust, banks would be unable to source money to lend. So, the more capital a bank has, the saver it is for depositors.

So, coming back to the Basel Committee. Since 1988 they have released three Accords, with Basel III being released in 2009. Again, without overcomplicating it, they recommend to the world’s Central Banks, (including RBNZ) that they require banks to hold a minimum level of capital. Basel II recommended a minimum level of capital of 2%. The GFC clearly showed that was not enough, and under Basel III that has now been lifted to 7%.

However, and here is the kicker, not all assets are created equal. All of the Basel accords have required banks to “Risk Weight” their assets. Simplistically, for example, treasury bonds are considered low risk, housing loans medium risk and commercial and rural loans higher risk. More than that though, under Basel III, all loans are individually risk weighted under a Risk Weighting Model and that feeds up to calculate the bank’s risk weighted assets, which then determines the minimum amount of capital it must hold.

Under the risk weighted model, a loan to a business that is well secured with a good profit history and outlook, will require a lower capital allocation than a poorly secured loan to a business with moderate to poor profitability. Furthermore, the increased capital allocation is not a straight line. It rises exponentially as the risk increases.

The Basel Accords talk about minimum capital adequacy ratios and have recommended a 7% minimum. However, the RBNZ are now wanting to go well beyond the minimum and are wanting banks to have a capital ratio of 17%. It is their view that the NZ banking system needs to be able to withstand a 1 in 200-year event. RBNZ cannot say what a 1 in 200-year event will look like. The GFC could be argued to be less than a 1 in 100-year event and the NZ banking system handled that. Maybe not comfortably, but it did handle it. Banks are pushing back hard on this, but whatever happens, banks, it would seem, are going to have to significantly increase the level of capital they hold. Where does that capital come from? The mostly Australian owners, and how will they react?

Another and significant change, which has slid under the radar is the Responsible Lending Code, which came into force in 2017, and is part of the Credit Contracts Act. The key part to this is the principle that Banks need to ensure the customer has the ability to repay the loan. You would think that would kind of make sense. However, over my time in banking, most clients only repaid their loan when they sold an asset.

Surplus funds were more often than not reinvested back into the business either for growth or development. It also means Rural Managers can no longer be the client’s advocate. Yes, they must retain a good relationship, but the blurred lines of conflict of interest have become much clearer.

The world everyone grew used to from 1990 through to 2008 and treated as the norm, has changed. There is now a new norm, and it may well be the new norm for some time. If this is the new norm for now, what does the future look like and how are you and your bank going to respond?

There are two things I know with absolutely certainty.

- I cannot predict the future. I used to think I could, but most of my bold predictions were proved to be wrong. So, I have shut down that part of my Business.

- Businesses that are operating at their optimum level and are constantly looking for increases in efficiencies and/or productivity (not to be confused with increasing production), will have a much better chance of success than those who just accept the default outcome.

Farming businesses must have a strong focus on profit, sufficient enough to allow debt to be repaid over 20 years. At current interest rates, that is likely to mean at least 3% of total debt being repaid per year. For example, a business with $5.0m of debt will need to generate a cash surplus of $150,000 after:

- Tax

- Personal drawings and

- Capital expenditure

That is all very well when nearly all product prices are above their long-term average. What happens when they are not? Now, more than ever, businesses will need to have strong clarity around:

- Values

- Purpose

- Vision

- A plan to achieve the vision.

Meanwhile, Banks will need to have a clear strategy on how they intend to adapt to an environment of increased regulation. They will need to have some difficult but necessary conversations. I am reminded of the nine Relationship Values we used at the National Bank:

Accessible, Follow Up, Keep Informed, Knowledgeable, Responsive, Prompt, Keep Promises, No Surprises, Error Free.

Add to that:

- Integrity

- Empathy

- Patience

Banks need to overlay those values with a culture that shows an understanding they are dealing with people and families who may be under enormous stress and not just financial. The banks that get this right will come out with enhanced reputations.

Banking and farming have always been a long-term game. There needs to be self-responsibility and a plan to a long-term solution. The change in environment will require a change in approach from everyone, which can happen quickly enough but will take time to cause effect. We need to rush at this slowly, or, as a wise 80 year old farmer told me recently we need to hurry up and take our time. Know and understand what has happened and react to it, but don’t panic, instead have clarity around the long-term strategy and be patient with time. That is for both farmers and banks alike.

Peter Flannery is a Southland-based Agri Business consultant, specialising in:

- Business Planning

- Financial Management

- Family Succession

- Equity Partnership facilitation

Following a successful 21-year rural banking career with the Rural and National Banks, Peter left banking in 2010 and along with his wife Margaret started their own company Farm Plan Ltd. For more information, on how Farm Plan may be able to help you, please go to www.farm-plan.co.nz