Nitrogen leaching losses can be significantly reduced, using composting barns, but it involves significant system changes a study has found. Anne Lee reports.

A study modelling the Lincoln University Dairy Farm’s (LUDF) nitrogen leaching losses with a composting barn shows significant reductions are possible even though cows are wintered onfarm.

But it would also mean significant changes to the farm system.

Former Lincoln University Bachelor of Agricultural Science Honours graduate now Perrin Ag consultant Rachel Durie, 21, explained the study she completed last year to the Fertiliser and Lime Research Conference to investigate how composting barns might affect production levels on New Zealand dairy farms.

She also wanted to find out what the critical components of the composting system are that affect the nitrogen leaching profile.

She used the LUDF’s 2017-18 data and data from a composting barn in use in Pirongia as well as information from industry experts and from published overseas research for her Overseer comparisons.

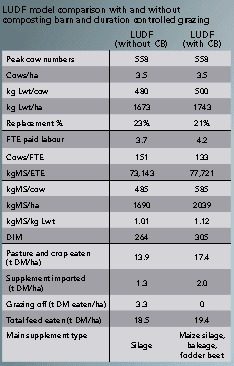

LUDF’s typical system was used and included all cows wintering off from mid-May to late July, replacements reared off-farm and 178kg nitrogen (N)/ha/year applied as urea.

No nitrogen losses from wintering were included. When Rachel modelled the system with a composting barn she had all cows wintered onfarm, grazing 12 hectares of fodder beet four hours a day over June and July and 24ha of maize also grown on the platform for silage.

The same amount of nitrogen fertilizer was applied along with compost from the barn, which equated to an extra 6.8kg N/ha/year.

Cows were managed under a duration-controlled grazing regime for the whole season with cows indoors for at least some of the day every day of the year.

The duration-controlled grazing regime:

- May to August – four hours grazing

- October to March – 12 hours outdoor grazing

- April and September – six hours outdoor grazing

Cows were fed in bins inside the barn but just outside the composting area so no outdoor feed pad area was needed.

The change in system, bringing cows home for winter using home-grown crops, meant cows were fed more supplement over the milking season with two tonnes drymatter (DM)/ha imported feed.

Rachel modelled an increase in pasture and crop eaten from 13.9t DM/ha to 14.4t DM/ha with total drymatter intake increasing (Table one) from 18.5t DM/ha to 19.4t DM/ha which in turn supported an assumed increase in liveweight from 480kg to 500kg and milk production, from 485kg milksolids (MS)/cow to 585kg MS/ cow with increased days in milk from 264 to 305.

Because Overseer doesn’t account for the composting process she made the assumption in the model that all liquid and solid effluent collected from cows in the barn was exported with the solid effluent then brought back on to the farm as an organic compost fertiliser, spread evenly over the soil at 1t/ha with a carbon to nitrogen ratio of 19:1.

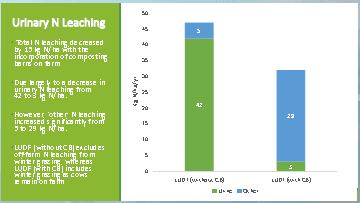

Based on those assumptions Rachel found Overseer predicted total nitrogen leaching to reduce on the milking platform by 15kg N/ha with the incorporation of the composting barns on farm – from 47kg N/ha/year to 32kg N/ha/year.

The reduction was due largely to a big decrease in urinary nitrogen leaching from 42kg N/ha/year to just 3kg N/ha/year thanks to the controlled grazing regime where cows were indoors for a significant time.

In Rachel’s modelling no account was taken of wintering losses in the “typical” or current farm scenario.

That meant the amount of leaching attributed in Overseer to “other” sources such as leaching between urine patches, faecal material and mineralisation of soil nitrogen through practices such as tillage, rose significantly from just 5kg N/ha/year on the “typical” scenario to 29kg N/ha/year.

She agrees that if apples had been compared with apples and LUDF’s losses from cow wintering were included in the typical scenario the total N loss reduction would have been even greater with the inclusion of the barns.

In her modelling losses from the maize crop were estimated to be 96kg N/ha and 150kg N/ha from fodder beet.

Rachel says the study showed that the composting barn provided the facilities to solve the urinary nitrogen leaching problems associated with pastoral dairying and that the reduction in losses can be captured by the Overseer model.

But the composting barns themselves didn’t reduce the nitrogen losses, it was more that they provided a method to carry out controlled-duration grazing.

They don’t have the fit-out costs of a full freestall barn and Rachel says studies show they compare exceptionally well when considered against freestall barns and standoff/feedpads in terms of animal welfare and cow comfort.

The composting barn also solved the issue of liquid effluent management that occurs with other barn types and some other feed pad/standoff set ups provided the barn was well managed and was designed correctly.

That includes the practice of tilling the composting loafing area twice a day to aerate the substrate,  increasing microbial activity and heat so the composting process takes place efficiently.

increasing microbial activity and heat so the composting process takes place efficiently.

In most cases people use sawdust but other materials were also under investigation – such as miscanthus, a fibrous tall-growing plant.

The barn also must be constructed to give adequate ventilation for animals.

While Overseer could estimate urinary nitrogen leaching based on the published studies on controlled duration grazing systems, Rachel says more work needs to be done on validating some of the models within the cropping assumptions – particularly for winter crop systems.

That highlights the importance of further investigation of winter feed systems that minimise nitrogen losses from soil mineralisation.

The other factor is ensuring greenhouse gas (GHG) losses don’t increase at the expense of nitrate leaching loss reductions creating a pollution swapping situation.

So the effects on GHG losses of composting barns particularly through increase in nitrous oxide production should be investigated, she says. Other soil types should also be modelled.

Rachel says she also looked at the financial implications of the composting system but they vary considerably depending on the farm location, system used and individual preference in terms of whether cows are fed in the barn and what additional concreting for turn-around areas or feed lanes they want.