The Meat Maker is the star breed to a Wairarapa farming operation. By Russell Priest.

For Tinui’s George Williams, the temperament and performance of the McFadzean Meat Maker composite far outshines any other beef breeds he’s farmed.

Primarily an Angus Simmental cross, the Meat Maker comprises about 75% of George’s herd. He focuses on the maternal type (one quarter Simmental and three quarter Angus) as opposed to the terminal type (three quarter Simmental and a quarter Angus blood).

“They are so laid back and their performance is impressive considering we work them hard,” George says.

“They clean out the rubbish among the rushes and the brown top thatch which smothers the clover if not removed.

“The ewes would die rather than eat that stuff.”

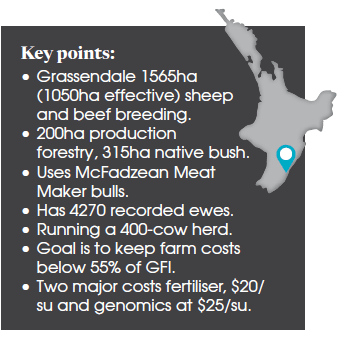

Past Wairarapa Sheep and Beef Farmers of the Year (2019), George and his wife Luce children farm “Grassendale” a 1565ha (1050ha effective) hill-country station 55km east north-east of Masterton. She is the third generation of Dalziells that have farmed the station. When George and Luce bought it off her parents in 2009 the station was carrying a high performing Simmental herd. Wanting to push performance, George increased the herd numbers from 160 to 400 while introducing the Angus blood to help moderate cow size. Under his management the role of the cow is to maintain pasture quality for sheep in a predominantly native grass sward so the day the bulls go out is the day the cows get screwed down.

“If you’ve got your cows still cleaning up pasture in June/ July you’re defeating the purpose of having them.”

The dry cow rate peaked at 15% and those that didn’t adjust were culled. The Angus cross calves were not in the same league as the Simmentals and needed to produce good weaners. Angus bulls were also too expensive.

George first saw McFadzean bulls as a shepherd at Wairere. Impressed with the progeny and the simplicity of using Meat Maker bulls without having to crossbreed, George began using them in 2013. He saw an immediate reduction in cow dry rate and both the temperament and the growth rates improved.

“The best calving we’ve had with them is 93% (calves weaned/cows to the bull) and we continue to thrash the cows to control the native pastures.”

Despite of the heifer calves only weaning at about 200kg the best 50 of these selected as replacements still manage to reach 400kg by November 20 (bull-out date) when they are barely yearlings.

“We push them along over the winter in their own rotation on grass and baleage so they get every opportunity to maximise their growth.”

George doesn’t have a cut-off weight for heifer mating but selects replacements on size and weight at weaning.

Using easy calving bulls

Low birthweight Angus bulls from Michael Kennet’s Waigroup-based 300 cow commercial herd are used for heifer mating. Michael specialises in producing easy calving bulls for the dairy industry. George often buys Michael’s older herd sires.

Heifers are mated for a period of 60 days after which they join the two-tooth ewes on the hills in their rotation. George believes running them on the hills before calving takes care of any potential calving issues.

Both heifers and cows receive two pour-ons, selenium before mating and a lice one before the winter.

The heifers calve on a flat paddock supplemented with baleage then moved to adjacent paddocks and grazed fed ad lib grass.

“They are so quiet and easy to handle it’s a pleasure working with them even if we have to intervene occasionally in the calving process.”

Bulls go out to MA cows November 20 at a ratio of 1:40 and a mating period of 60 days. Mixing yearling and MA bulls together in the mating mob astonishingly results in little fighting and few injuries.

“They are so placid they just don’t seem to be interested in scrapping.

He likes to buy bulls in pairs so they are familiar with one another and are less likely to fight.

“If we do get a troublemaker he’s culled.”

The calving date allows lamb weaning and shearing to be completed before the bulls go out. Secondly, it allows the cows to be set stocked for calving in the ewe paddocks after they have lambed.

Cows and calves follow the ewes over the summer tidying up pasture. After weaning in March the cows are mobbed up and used to remove any remaining roughage on the hills before going into a 200ha forestry block for three months from May to July. Having a large area to winter cows is a significant asset while also generating substantial future income in the form of logs and carbon credits.

“The cows probably won’t see the forestry block this year ‘cos we’ve had such an exceptional summer there’ll be plenty of clean-up work to do.

“Our neighbour said he hasn’t seen a summer like it in 40 years.”

Scanning the herd for dries, singles and twins reveals on average 12 cows are carrying twins. Separated from the main herd at weaning, these are wintered with the weaner heifers and calved separately with most rearing their two calves.

George says the bumper season they’ve had has resulted in the best calves he’s seen. He admits it’s much easier on the eye that way and maybe has been working them a little hard in the past. In spite of this, the herd still contains cows that are more than 11 years old.

He has learned through experience the secret to successfully farming breeding females is to know when their intake can be reduced and when they need to be fed well.

A strong advocate of turning over the generations as quickly as possible, George admits bulls are getting too expensive to follow this philosophy. However, he’s still prepared to pay top money for his Meat Maker bulls last year outlaying $8000 for a yearling. The fact that bulls are sold with only raw data doesn’t concern him but he does pay close attention to the pedigree information, being particularly keen on any Kerrah Simmental blood.

“They come from a 1000-cow herd, suit what we’re trying to do, are exceptionally quiet and have good longevity. It’s also a simpler system having just the one breed involved.”

A trading cattle component has been added to the business following the dropping of cow numbers to 280. All Meat Maker weaner heifers are wintered with the 70-80 culls being sold in early October in Feilding at 380-400kg. Providing valuable cashflow, it also frees up scarce flat land for about 1000 sale rams coming off the hills.

After selling the Meat Maker steer calves to a regular private buyer at 230kg for $775 last year, Grassendale bought 50 Angus steer calves for $500, wintered them on grass and sold them in the spring for $1100.

Sheep goal efficiency and productivity

The sheep generate a large part of the income. Grassendale has 4270 recorded ewes consisting of 2300 Romneys, 1000 Romworth, 600 terminals (mainly Beltex Suftex cross) and 370 facial eczema-tolerant composites (Perendale x Romney x Coopworth).

George believes successful sheep farming rests on efficiency and productivity, finding the breed and strain of sheep that best suits the environment.

“Our biggest genetic challenge with the Romneys is to achieve a higher performance at a lighter bodyweight and with the aid of genomics and detailed sire summaries significant progress has been made.” When selecting rams, George places a lot of emphasis on the maternal index which has a significant negative weighting on mature size. They must also be structurally sound, clean around the points and have a 34 micron fleece with a quality score of seven.

Romney and Romworth ewes plus 1200 commercials are run on Grassendale while the other two flocks are farmed as a joint venture with George’s cousin. The ram lambs from these flocks are run on George’s brother’s place near Masterton. This helps ensure the genetic integrity of the breeds.

Between 700-800 rams a year are sold to 114 clients at prices between $1000 and $2000.

Most rams are sold privately however a small number of Beltex Suftex cross rams have been sold at auction with last year’s averaging $1900.

All stock on Grassendale are run commercially to simulate the conditions under which commercial clients are likely to farm their flocks.

“Acclimatising rams to a harsh environment so they perform well for our clients is what we’re endeavouring to do.”

Being traditionally summer-dry, Grassendale provides plenty of challenges in particular the early autumn. The biggest of these is feeding the capital stock and replacements including ram hoggets. Feed was so short one autumn poplar trees on the hills were felled and the leaves fed to the ram hoggets.

Depending upon the season, ewes can be grazed in a rotation (when there is reasonable summer rainfall), block grazed or set stocked. Rotational grazing is Grassendale’s preferred option but is seldom possible because feed runs out. Block grazing is the default option as George is not a fan of set stocking. Grazing a block of 150ha at once the ewes are shuffled on when the feed starts to get short.

“Using this system ensures you’ve always got something up your sleeve.”

As soon as autumn rains arrive 150kg/ha of DAP13S is applied. Now a low priority mob, the ram lambs get mobbed up and the area used for ewe mating is spelled.

Single-sire mating constraint

Requiring 30 paddocks for single-sire mating from March 20 really complicates management as these paddocks effectively become set stocked for 34 days (two cycles). This constraint significantly compromises the ability to build up winter feed reserves as rotational grazing is not possible during this period.

“Fortunately mating is more or less over in 20 days but if rain doesn’t arrive by March 15, generating a wedge of feed for the winter can be further compromised.”

DNA for pedigree identification enables Grassendale to use multiple-sire mating groups and the nucleus-multiplier concept to generate large numbers of genetically superior progeny for the benefit of its clients.

Post-mating, ewes are mobbed into two groups (two tooths and MA) and the winter rotation begins. George would ideally like to get this out to 60 days however this is seldom achieved. George believes it’s better to maintain ewe body condition through the winter rather than try and put it on before lambing.

Scanning in mid-June identifies dry ewes and those carrying multiples and singles. The dries are culled while the single-bearing ewes are immediately locked up with the cows in a large paddock. The multiples go on to a daily shift.

Multi-bearing ewes are set stocked on the easier hill country at 5.5/ha and the singles on the steeper more exposed country at 6.2/ ha. Scanning averages 177% (140 – 145% lambing) with George freely admitting he doesn’t want it any higher than this.

Unfortunately high scanning percentages mean high numbers of triplets and after such a growthy summer/autumn,more than usual are predicted. “In spite of not giving the triplet ewes any special treatment we still have ewes that wean three good 29kg lambs.”

Lambing time on Grassendale is far busier than most sheep farms as the 3300 recorded Romney and Romworth ewes need to have their lambing details recorded and their lambs tagged. Quietly moving through the ewes once a day on foot, horseback or quad, each shepherd is responsible for his/her own block. Making this considerably easier are the EID (electronic identification) tags carried in the ewes’ ears. Once each ewe is identified on the operator’s hand-held device her lambing data can be recorded and immediately sent back using wireless technology to a home-based computer. EID technology has greatly enhanced the amount of monitoring possible. Most of Grassendale’s drafting is done using pre-selected drafting lists and a five-way auto drafter.

“Our weighing system can process and draft 700 animals an hour.”

Ewe must have lambed as hoggets

Condition scoring and weighing the recorded ewes at weaning and mating provides valuable information for SIL to estimate mature weight breeding values which are of particular interest to George.

A prerequisite for entering the Grassendale recorded flock is for ewes to have lambed as hoggets. Selecting the best 1150 ewe lambs early on size and accelerating their growth rate using crops and grass results in about 1000 getting in lamb. The smaller ewe hoggets are often grazed off the station.

“Our whole focus with hogget mating is to minimise wastage by growing them as well as we can so that they reach a satisfactory weight as two tooths and rebreed.”

Hoggets are run with terminal rams from the end of April for two cycles Last year the two hogget mobs averaged 40 and 42kg but George confessed he would rather use a minimum cut-off weight of 40kg.

Grassendale’s drenching philosophy is based on minimal use and refugia. Ewes are not drenched and lambs are only drenched sparingly. Lambs’ faecal egg counts are monitored after weaning particularly in the autumn when Barbers Pole can be an issue.

“We are trying to breed sheep that don’t require drenching.”

Selecting for neither resistance nor resilience but for production means anything that has to be drenched or is not performing in a large mob situation is culled.

With George away so much, a lot of managerial responsibility is placed on his staff. They include Joshua Volman (manager), 25, Sam Peffer, 24, and Nico Bresaz, 20.

Rising to 330m asl and subject to strong nor-westerly winds the contour on Grassendale is mainly medium-to-steep with only 115ha cultivable. Annually 30ha is sown in Raphnobrassica providing a summer green-feed crop mainly to accelerate the growth rate of ewe lambs to enable them to achieve satisfactory mating weights as hoggets. The cropping programme also aims to introduce more drought-tolerant cocksfoot into the pasture mix. Average paddock size is 12ha.

Based on sandstone, siltstone, mudstone and argillite the soils are prone to serious erosion. Working closely with the Wellington Regional Council land management group, George and his team plant 500-600 willow poles a year for erosion control.

“It’s awesome working with those guys. Without their expertise we wouldn’t be able to farm this place.”

Luce’s father John put a lot of effort into soil fertility. With most of the soils not being inherently fertile the Olsen Pand PH levels of 18 and 5.7 respectively on the hill soils are commendable. Typically low on sandstone and argillite soils are the sulphur levels.

With so many clients to service George chooses to spend a lot of time on the road visiting them and familiarising himself with their individual farming situations. “I discuss all sorts of issues with them including any concerns they have with their rams.”

George is concerned about the loss of so much good hill country to carbon farming.

The encroachment of forestry has also brought an explosion in the population of feral deer.