Penny Back

Research at Massey University is investigating heifers who have had broken shoulder bones and need to be put down, with considerable economic and potentially genetic loss.

While some farmers may not have seen the condition, many others have or know someone who has encountered it – with losses reported of 2-25% of first-lactation heifers in some herds since it first arose in 2008.

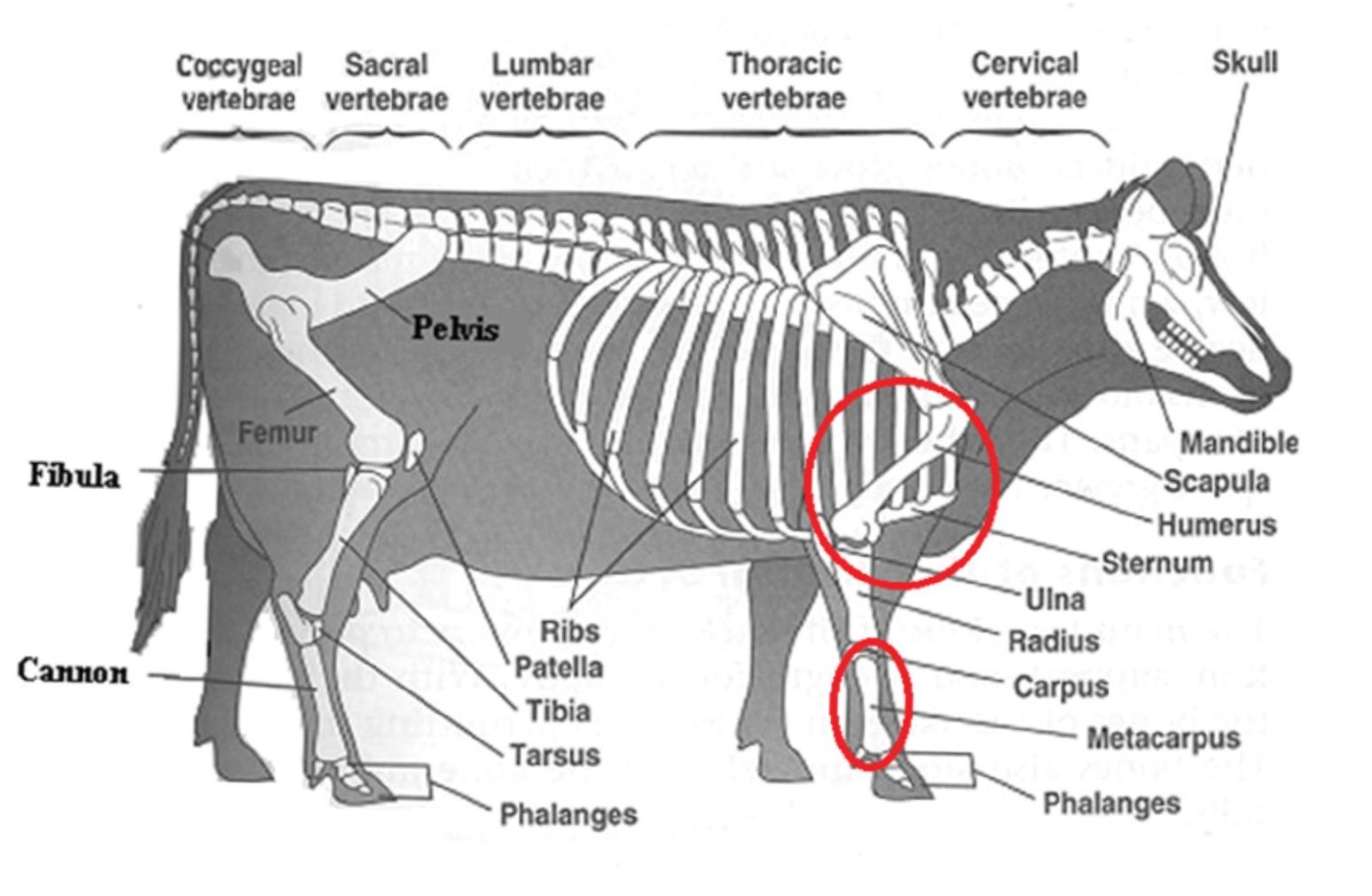

A ‘broken shoulder’ is a spontaneous humeral fracture, which occurs with no warning and requires euthanasia of the animal as the fracture can not heal, Massey University senior lecturer in dairy production Penny Back says.

The humeral fracture is a complete spiral fracture caused by osteoporosis and a decrease in cortical bone thickness (the wall of the bone) , as shown in post mortem examinations of the broken humerus bone.

This means the animal has a similar bone length to an unaffected animal but the bone has a reduced diameter and mass (density). This reduced diameter and mass results in a weaker bone which is important as the humerus is a bone under huge strain due to muscles in the shoulder.

The ‘broken shoulder’ condition is commonly seen in two-year-old, first lactation heifers from later pregnancy to several months after calving but has also been seen in older animals. This indicates that the condition may be caused by multiple factors, which all contribute to weak bones.

Preliminary work indicates periods of inadequate calf and heifer nutrition (and in some cases copper deficiency) impacts bone growth and development. Combine this with improving genetics for milk production, which increases the draw of calcium from bone in early lactation, increasing the likelihood of fractures.

Preliminary investigations of the project have shown not a lot is known about the effect of some of the factors, like the amount of feed, different feed types and feed restrictions (through droughts and winter scarcity) which can cause growth checks, potentially have on heifer bone growth.

“We know that peak bone mass in cattle is influenced by factors prior to puberty and insufficient peak bone mass in the first lactation predisposes heifer to risk of spontaneous humeral fractures,” Back said.

Not a lot is known about bone growth in heifers so the project is looking at how normal bone growth occurs, and where disruptions in bone growth and development are occurring in young animals in New Zealand’s seasonal system, which may predispose them to fractures.

The first publication of the project can be found here.

How do heifer bones grow?

As the bone is growing, the size (length and diameter) of the bone increases. To do this, ‘scaffolding’ is erected and once it reaches a certain size, it stops. Subsequently this ‘scaffolding’ is back filled to increase strength (the density increases).

This is an ongoing process. What appears to be happening with animals having fractures is that the bone builds its ‘scaffold’ for size (so they don’t physically look different to unaffected animals) but don’t appear to be able to backfill the ‘scaffold’ so the bone the lacks density and therefore strength.

Researchers don’t know what limits the bones’ ability to do this process, particularly at a young age. Given the range of systems used to rear our calves, they need to understand if there is not enough energy or protein available for the bone to be able to develop properly, resulting in a weak bone that can not withstand the need for bone turnover to provide the calcium required during early lactation.

The project members are Chris Rogers, Keren Dittmer, Rebecca Hickson, Penny Back and two PhD students, Michaela Gibson and Alvaro Wehrle Martinez. The project is focusing on growth of young animals (Michaela’s PhD project) and the effect of diet (Alvaro’s PhD project).

Follow their FB page: Massey heifer fracture research group.