Keeping it simple is paying off for the Bartons in West Otago, Lynda Gray reports. Photos by Chris Sullivan.

Two-time West Otago two-tooth competition winners Sam and Liz Barton are driving production to cancel out cost creep.

“Most of our costs are fixed and to cut any would potentially mean that our production and profit would take a hit so we’re concentrating on output,” Sam says.

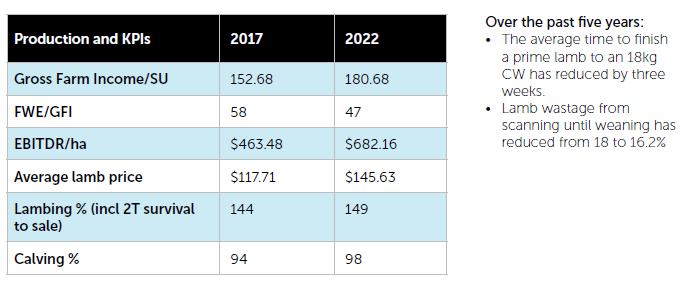

Their production focus and a keep it simple stupid (KISS) management philosophy appears to be paying off judging by their key performance indicators.

Sam is quick to point out that the almost $30 gross farm income per stock unit and $220 EBITDR/ha improvement over the last five years is reflective of the 20% increase in lamb prices. But over the same time the Bartons have managed to further push production through breeding and feeding changes which have transpired to an increase in lambing performance, and reduction in lamb wastage and the average time to slaughter.

They first won the two tooth competition in 2019. Although proud of their success they told Country-Wide (May 2019) there was a lot of unfinished business and scope to further improve sheep flock performance.

Reducing lamb wastage from scanning to weaning was high on the list and they’ve managed to knock that back from 18% to 16% by tightening up body condition score (BCS) targets and treating potential iodine deficiency with a Flexidine injection.

The Bartons had always condition scored ewes at weaning and preferentially fed the lighter ones in the lead up to mating. However, in 2019 they raised the BCS cut-off for preferential feeding which has resulted in better condition ewes at mating and a higher rate of conception.

“We’re comfortable with wastage at 16% but whether that’s sustainable I’m not sure because it’s largely dependent on the weather at lambing. We don’t want to fall below 140% lambing (survival to sale) and over the last six years we have averaged 144%, ranging from 141 to 151%.”

On the feeding front, the introduction of Cleancrop leafy turnip last year for finishing lambs has been a significant production boosting move.

There were two main drivers for growing it: the washout of spring cultivated established permanent pasture two times over the past five years, and Intensive Winter Grazing regulation (subsequently amended) requiring new crops to be in the ground by October 1.

The crop is direct drilled into eaten out crop paddocks by October 20 and at the end of March is cultivated and sown in permanent pasture for lambing in spring.

Last season Perendale crypts got three grazings, and the top tier achieved live weight growth of 583 grams per day – about twice as much as what was possible on pasture.

The crop cost $14,500 to establish ($675/ha) so from a strictly cost-benefit analysis it doesn’t add up. But Sam says it stacks up well from an overall system perspective.

“It gives us feed security for dry years as well as the opportunity to add extra weight to other classes of livestock on the pasture that would otherwise be grazed by lambs. It’s also pushing feed forward until the end of April and therefore reducing the need for nitrogen on pasture.”

Although the Bartons are taking an increased output approach to help cancel out the effect of cost creep, they’re also minimising unnecessary expense where possible. The direct drilling of crops to save on tractor hours is one example; a more strategic approach to nitrogen application is another.

“We tend to view nitrogen as an ‘ambulance at the bottom of the cliff’ type action, but at the same time know it helps establish crops, especially those that are direct drilled.”

They used to apply 180kg/ha DAP across the farm in mid-March, for maintenance and to boost pre-winter covers, but that’s not needed with the introduction of the leafy turnip which has reduced the grazing pressure on the wider system, pushing pasture covers till the end of autumn. Also, the Bartons were keen to move away from DAP due to the negative effect on pH.

Now 300kg/ha of Superplus along with potassium and selenium prills are applied in January. Although the change isn’t saving any money, the deferred payment until March is a help. Another advantage is safer ground conditions on the steeper hill country for bulky application in summer.

The Bartons are also keeping an eye on shearing expenses, given the May announcement of the 7% increase in shearing costs for crossbred sheep, although they believe the increase is justified. They’ve skipped the increase in the meantime by shearing all the ewes before July 1. The ewes are belly crutched in the autumn, and shorn pre-lamb. Only the replacement ewe lambs are shorn.

“We believe that with the high quality genetics we’re using and the high ME feed it’s not necessary to shear the terminal lambs to increase growth rate.”

In another move to contain farm expenses all the herbicides needed for the 2023 growing season have been bought in advance. Also bought and in storage are pipe, fittings, tanks and troughs for water scheme developments across the farm.

On the breeding side, Perendales replaced Romney as the preferred maternal sires in 2020. The Bartons shopped locally from Richard and Kerry France of Hazeldale whose rams meet the physical and genetic checklist.

“Given that they’re relatively close neighbours, I felt there was a good chance that their genetics would transfer successfully, and it’s proved to be the case.”

As well as being in the top 20% for SIL maternal, survivability and growth traits they have a good spring of rib, heavy bone, a medium-type wool and a clean head and ears.

The hybrid vigour is apparent in the offspring; they’re definitely more of a challenge to handle than the Romney sired progeny. Sam says they’re open minded about whether Perendale sires will be used for the long term.

“Our plan is to review the Perendale influence after five to seven years. We can always go back to Romney to inject hybrid vigour again, but we’ll never go along the composite line for a maternal flock.”

In another breed change Kelso terminals from Meadowslea Genetics replaced the Sufftex rams from 2020.

“It’s early days but the lambs have been outstanding so here’s hoping that continues.”

Keeping notes

Monitoring and measuring is second nature to progressive farmers such as the Bartons. Their efforts at recording key data were acknowledged in the winning of the agri-science category of the 2020 Otago Ballance Farm Environmental Awards.

Interestingly, Sam takes the old school pen and paper approach to recording all the data. He has a stack of 23 hard-backed farm diaries spanning his entire farming career, the page in each recording key data and points of relevance.

He’s deliberately steered clear of online farm management software and platforms.

“I don’t think they give enough scope to add in thoughts and comments and I believe we spend too much time looking at our phones these days, it’s not great for our children.”

He’ll often add in his diary entries a note about something that went well or not so well.

His most recent note to self was to never, ever buy store lambs late in the season. This year, encouraged by the surplus growth, they bought for the first time ever 450 stores in the first week of April. Soon after a dry period kicked in at the crucial pre-tup feeding time causing a lot of stress. They ate about 1000kg drymatter a day over the 52 days – the equivalent of 216 bales of balage. After grazing kale for 23 days the lambs were taken off at 42kg LW-plus and killed out at 16.5kg.

“It was very disappointing. We took a hit, and it wasn’t good for our mindset. Luckily May and June was very kind to us, so we got ourselves out of jail.”

Benchmarking performance

Sam and Liz have in effect benchmarked their own farming performance by entering farming competitions, winning this year’s West Otago two-tooth competition and best ewe hogget flock. A particular highlight was the acknowledgment by one of the judges of their passion and energy to succeed.

“We were a bit taken aback and it was a special moment to hear them say that,” Sam says.

They were first time entrants in the 2020 Otago Ballance Farm Environmental Awards and won the livestock, quality water and agri-science categories. They were encouraged by their equity partners Phil and Jenny McGimpsey and are glad they did.

“Our goal was to win the livestock award, the other two awards were a nice surprise. The judging was a great process to go through and we learnt so much and made some great connections.”

The connections have included an invitation to join the ‘Growing Future Champions of Good Practice’, a NZ Farm Environment pilot programme to be trialled throughout the Otago region over the coming year. The intention of the programme is to mentor young farmers with input from rural professionals and experienced successful farmers on how to develop their business within a best practice framework.

Another project is ‘What’s possible together’, a Ballance Agri-Nutrients backed ‘farmers-leading-farmers’ initiative in which the Bartons along with other motivated farmers throughout the country will implement and showcase management and tools for driving farm performance and environmental sustainability.

“There’s a lot of negativity about environmental regulations, especially from the older generation. But our view is not to fear them, and we want to prove that our farm can be both environmentally sustainable and profitable.”

The Barton and McGimpsey equity partnership Montana Pastoral continues to work well. In a recent restructure the Bartons bought stock and plant, while retaining a 20% share in land and buildings. The buying of stock and plant has taken the pressure off without compromising on-farm performance, Sam says.

“A big focus is to continue growing our equity but not at the expense of our lifestyle.”

It’s about finding the right balance, which is difficult given their full-on stage of juggling the farm, community commitments and a young family. Sam is president of the Heriot Collie club and a member of the Eastern Southland LandSAR with Liz providing the crucial behind-the-scenes support.

Sam likes the thinking of an older and successful farmer who once said balance is eight hours’ work, eight hours’ play and eight hours’ sleep.

“It’s a good guideline and something we’re trying to do as a family.”