Despite a late start and bumps along the way, the O’Malleys have achieved

farm ownership in their target West Coast district. By Anne Hardie.

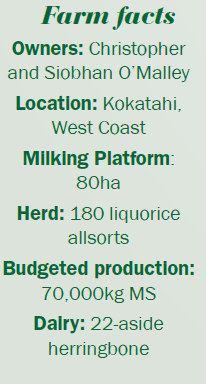

EVERY FENCE POST, TREE, CLOD OF dirt and shed on Christopher and Siobhan O’Malley’s 80-hectare farm near Hokitika belongs to them after successfully reaching their goal of farm ownership. The city-born couple who were late starters on a career path in the dairy industry have got there through scrimping, saving and selling, with no financial help.

The thermometer goal chart on their fridge shows the gradual climb in savings that was needed to get them over the line with the bank for financing their farm purchase. Their three kids knew the importance of that thermometer and helped colour it in as it grew toward a target of $300,000 cash in the bank to bolster the equity built up in a liquorice-allsorts herd of cows.

When they first began to dream about farm ownership – and Christopher confesses they are big dreamers – the idea of spending millions of dollars was beyond their comprehension and even beyond their conversation. So they forced themselves to talk about big numbers to build their awareness and confidence.

“We just struggled to even talk about big numbers because our life experiences didn’t have numbers of that scale,” Siobhan says. “We started to talk about a $3 million farm even when we only had $20,000 in equity so we weren’t intimidated.”

“If you are too scared to talk about it, you can’t do it,” Christopher adds.

The O’Malleys are well known in the industry after winning the Sharefarmer of the

Year title in the 2017 New Zealand Dairy Industry Awards and also for their innovation. Siobhan is a co-founder of the Meat the Need charity where farmers donate livestock and more recently milk to be processed, packed and delivered to city missions and food banks around the country.

More recently she has teamed up with Merino farmer, Paul Ensor, and sales and marketing powerhouse, Harriet Bell, to produce a merino-hemp yarn called Hemprino. It has meant travelling to China on an Agmardt grant to complete research and development with a yarn manufacturer to combine the two fibres for the startup.

Both began careers far removed from dairying. Siobhan followed her passion when she left school and gained a degree in Classics, including Latin, and though she says it taught her to think and analyse things, job pathways were scarce. Consequently, she added teaching qualifications and became a secondary school teacher.

“I was told to study what I enjoy and a career would sort itself out – which is a misleading statement in Classics.”

Christopher headed into adventure tourism and spent several years having a wonderful time in places such as the Abel Tasman National Park, guiding kayak trips and then Ireland when they spent time there on their big OE. But it wasn’t leading to a career.

Returning from Ireland in 2009, Christopher got a job as “the boy” for his brother, Ant, who had a lower-order sharemilking contract on a Canterbury farm. He had some inkling about dairying – or at least milking – after spending holidays on his grandparents’ small dairy farm at Kokatahi inland from Hokitika where they milked 40 cows. His grandparents had a ballot farm just a stone’s throw from where Christopher and Siobhan now live on their own farm and he says it is a bit like returning to his turangawaewae.

“I feel like I’m where I should be.”

Pushing for progression

Starting later hasn’t held them back in the industry and Siobhan says it was in some ways a gift because it meant they had no preconceived ideas about dairying and they followed their own path.

Progressing their career in dairying has meant moving constantly, often between regions and Siobhan says those working in the industry sacrifice their connections with communities when they move to other farm jobs and it isn’t easy. It is one of the reasons they aspired to farm ownership where they could have a permanent home for their children, Finnian, 10, Aisling, 8, and Ruairi, 6. Siobhan has an Irish background from generations back and the Irish names are a family tradition.

“I was lucky enough to find someone with an Irish surname!”

Between that first Canterbury job and farm ownership, they have had five sharemilking contracts between Canterbury, North Otago and the West Coast. Along the way they entered the Dairy Industry Awards three times which culminated with winning the national title. The first time they entered in 2013, they were variable-order sharemilkers in the West Coast’s Grey Valley. That first entry was all about finding out about the awards and using it as a learning experience. They won a couple of prizes and learnt a lot.

When they entered again in 2015 when they were variable-order sharemilkers in North Otago, they admit their entry was a train wreck. They were trying to juggle their entry and all that entailed at the same time they were looking for a new job before the farm they were on was sold. Travelling to job interviews around the South Island took precedence over the awards.

They moved on and in 2017 as herd-owning sharemilkers and with three young children, they spent months working on their entry after the kids were in bed and were confident by the time they presented their business to the judges.

“It became a bit of an obsession,” Siobhan admits. “But through that process we thought there was no bloody way we were going to be able to buy a farm.”

Back in 2013 when they were lower-order sharemilkers they discussed the goal of buying a farm on the West Coast, but their accountant initially laughed at their idea of the timeline to get there. But they hadn’t given up on the idea.

Then they won the sharefarmer of the year award and were offered some opportunities to become equity partners. But when they sat down and worked through it, they realised they just didn’t have the money to do it and they didn’t want to be a long-term minority player in a partnership.

Disenchanted about their goal for farm ownership and burnt out from years of chasing the goal, they quit the industry.

A new direction took them to Motueka for something completely different – managing a small hop garden and beef operation. It was an interesting

interlude and they learnt about a different industry, but it wasn’t what they were after.

In 2019 when they were still working with hops, they went to the West Coast to be judges for the regional awards and returned home fizzing. It made them acknowledge their love for dairy farming and they wanted to get back into it. Not just anywhere though – they wanted to be on the West Coast where they could settle into a long-term community. And they wanted to chase that goal again of farm ownership and this time make it happen.

Two years ago and back on the Coast with a sharemilking contract, they had a herd of 400 cows and $100,000 in the bank which wasn’t enough to buy a farm and they had spied the farm they wanted just by the Kokatahi-Kowhitirangi School. West Coast farms were sitting on the market for a long time after years of Westland Milk Products’ low payouts before Yili bought the former cooperative.

The bank required them to have $300,000 in savings and in the past two years they have managed to add another $200,000 and the thermometer goal chart shows that progress.

Last year Siobhan took on a full-time teaching position at the local secondary school so they would have a history of regular off-farm income to help tick the boxes with the bank. To buy the farm, they sold more than 200 cows and took the leftovers with them, confident that feeding them right and looking after them will produce results in the vat.

“We knew if we fed them well we could do well because we knew our skill set,” Siobhan says.

Counter cyclical with cows

Throughout their dairying career, they have been making equity gains by buying the cheapest herds, then looking after them so they could resell the herd when prices peaked. Christopher says banks don’t grade cows, so whether it is a top BW cow or one with three teats, it is all the same to the bank when it comes to equity and for sharemilkers striving to buy their first farm, it is all about equity.

“We had 400 cows including some empties and sold the best. That left us with old girls, three titters, unwanted and a smattering of half-recorded cows which left us with a ragtag crew to take us through this year. But the bank value is the same as the cows we just sold, so that’s your equity.”

Twice in the past they have sold A2 cows from herds they have purchased and replaced them with other lines of cows at a lower price so they could put money in the bank. The first time they sold A2 cows was during the 2015-16 season which was their first year as 50:50 sharemilkers and the payout plummeted to $3.80/kg milksolids (MS).

Siobhan says they still have post-traumatic stress from that year and many sharemilkers were lost from the industry. They traded about $200,000 in stock that year and between trading and milk

production they ended up with a profit of $10,000 for the year instead of debt.

They have always paid low prices for their cows. The first herd they put together was cheap at an average of $1175 per cow and their latest herd of fully recorded cows cost them on average $1050 per head landed. They bought the herd in late May when herds are traditionally cheapest because people are desperate to find a new home for them. In a poor year, cow prices are up to about $1500 and in a top year they can be up to $2200. Buying cheap has enabled them to carry less debt and make the most gain.

When they sell cows, they sell them before Christmas when most buyers are wanting certainty about their herd for the following season and will pay a premium to secure cows. The 200 they sold to buy the farm were sold before Christmas but stayed in the herd through to the end of the season. They had previously bought them in May, so there was a good margin when sold, even if they did not get the highest price in the market. Christopher says you have to be prepared to take a risk when you don’t buy your herd until May. But buying herds late in the season has worked for them.

“We’re counter-cyclical investors.”

“It sounds risky, but it’s downside mitigation,” Siobhan says. “We would pay up to $1500 for a cow and once paid $1600 which was outrageous for us. As herd owner/sharemilkers we were obsessed with cow prices and what buyers were looking at for breed and BW and PW.”

“You are always thinking about selling your herd, because you have to sell,” Christopher adds.

They also synchronised their heifers last year, used sexed semen and calved slightly earlier than their neighbours so they could sell the cows to a wider market of buyers.

Reaping rewards of perseverance

Getting to the finish line, they moved on to their own farm on June 1 and Christopher says he is immensely proud about farm ownership.

“You can sometimes shoot for the stars and miss,” he reflects. “You work really hard to get there and if you are always going to be sharemilking, you never have that security and that is what we were after.”

“That’s why people choose equity partnerships,” Siobhan says. “It allows them to choose a piece of a farm and settle there. But that would have started to annoy us and we would rather be milking on a small farm for ourselves. That was just our personality. We really wanted this.

“We’ve been sprinting and really focused on this for a really long time. So it’s nice to go on to the next thing which is to pay it off.”

The Kokatahi-Kowhitirangi School is right next door to their farm and the kids know this is home and they won’t be moving any time soon.

“There’s a sense of relief,” Christopher says. “Not just for us, but also the kids. Now they have a home that is theirs. Because you are really renting homes when sharemilking.”

The kids knew the goal as Siobhan and Christopher talked about it openly in front of them, including the money they needed to save to make it happen. It has meant living frugally to keep debt down and save pennies – apart from one year when they splurged on a holiday to Australia.

“Five years ago they knew Dad had to milk the cows to put milk in the vat for the tanker to come for Fonterra to take milk and pay us so we could go to Australia.”

West Coast of opportunity

Apart from family history and community, the Coast was the logical region to buy a farm. Land prices between $20,000 to $25,000 per hectare are half Canterbury prices, yet the farms produce more than half the production per hectare of those Canterbury farms which makes for better cash flow.

“We had to learn how to farm in the climate and how to manage the animals and land in this climate

and so we were sharemilking here before we bought,” Christopher says.

Before buying the farm they also talked with the farm’s owner and neighbouring farmer who had lived there for 50 years and was able to provide information that will help them through their first season.

This spring, they are milking 180 cows in their very own dairy – a 22-aside herringbone. Young stock are grazed off and most of the cows were also grazed off through winter. They are budgeting on 70,000kg milksolids (MS) and plan to feed about 400kg DM of palm kernel to the cows, mostly through spring to Christmas. Then they will reassess and may cull some cows rather than buy-in more feed.

They will focus on keeping a lid on costs and any surplus will be used to “smash the debt”.

Siobhan continues to be involved with Meat the Need on a voluntary basis and the Hemprino brand as a business venture. If that wasn’t enough, the pair also want to be involved in the direction of the dairy industry. This year Siobhan starts a new role with Muka Tangata: Workforce Development Council for food and fibre sector and Christopher is chair of the West Coast Focus Farm Trust.