Northland dairy farmers are getting together with graziers to better-prepare young stock. By Delwyn Dickey.

Winters in Northland are usually fairly mild. And while pasture growth slows it doesn’t tend to stop altogether.

This sees autumn calving becoming a more popular option for northern farmers so young animals aren’t then going straight into a dry summer and poor-quality grass.

Dealing with the northern summer was just one of the things that came up in discussions at a recent SMASH field day held on Brian and Rachael Cook’s farm near Kerikeri, in the Bay of Islands. The field day was aimed at advising dairy farmers and graziers on the importance of hitting target weights for young heifers in Northland, along with how to build and maintain good relations between the two groups

Like most farmers new to grazing, Brian and Rachael have been learning the ropes and have got to grips with the needs of the “softer” dairy heifers they are raising, compared to their own hardy beef stock.

The farm they have been leasing for the last few years has 110 hectares of pasture with a lot of kikuyu on it. They are running 100 head of their own beef cattle and 20 beef/dairy cross cows.

Keen polocross players, they also have 16 horses, which are also part of the pasture rotation – especially in winter, which Brian reckons is good for both the horses and cattle as they aren’t affected by the same parasites. They each mop up the parasites of the other species as they eat.

They couple got into grazing young heifers after talking to a local farmer who wanted somewhere to graze his 80 autumn calved heifers. The numbers seemed a good fit for their land and they agreed to take them on.

“This was a way to stock the farm without buying all the stock ourselves, and keep the cash flowing until our own beef animals start to come through,” Brian says.

While the stocking rate was about right it was still a struggle that first winter.

The Cooks’ south facing land is a little cooler in winter so the grass doesn’t grow quite as much. The upside is it also doesn’t dry out as much in the summer so once spring arrives, they have better-quality pasture than many.

The second year the couple made a change to the contract so the youngsters came on to the place at 90kg or more. If they come on under 100kg the owner is asked to supply meal to get them cranking at the start.

The meal does the trick although with the very wet winter this year the youngsters didn’t take off as much as expected. While they are piling on the weight now, they were behind target.

Regularly weighed at drenching sees Brian now comfortable with the heifers putting on 0.3kg per day through winter as they haven’t been able to achieve more than that. Once spring arrives the R2’s are putting on more than 1kg a day before settling back to about 0.8kg a day.

Being a vet has made taking care of the health of the young animals easier for Brian, and also gave the owner confidence in the couple as first-time graziers.

Though there is nothing in the contract about what treatments should be used Brain is very particular including with drenches, with animals drenched as soon as they come on to the property.

“You don’t want someone else choosing drenches that aren’t as effective as what you use,” he says. “Any worms they bring on to your farm stay on your farm even when the stock has changed. If drench resistance comes onto your farm, it’s your farm’s problem.”

He has worked with Wormwise, to check the drench they’re using is working – and to date there is no sign of resistance or drench failure.

While comfortable with how the venture is going, Brian has been surprised at the difference between the two types of livestock.

“The dairy heifers need more care and attention than the beefies. They need to stay on the better pasture, we need to keep them growing constantly and they need more attention – particularly over winter.”

Brian reckons having the beefies also makes managing the heifers easier, as they found out this exceptionally wet winter, which slowed pasture growth. The heifers were able to get the premium pasture.

“The beefies can go on the rougher pasture and still do well, and they can handle a period of slow or no growth,” he says. “They’re a hardier animal, designed to forage better than dairy. They get minimal supplement feeding compared to the dairy heifers.”

With ambitions to breed beef stock in the future, the couple intend to continue as graziers as they head toward that goal.

A handshake and good communication are key

Peter Giesbers has been sending his heifers off-farm in the Kaikohe and Ohaihau areas, for 18 years and reckons he’s never signed a contract, instead having a verbal agreement and a handshake. The success of this comes down to good communication, he says.

The few graziers he’s had during that time have continued to raise his animals every year for five or more years and there has been plenty of trust on both sides.

He has been sending about 60 animals each year to his latest grazier whose whole business consists of raising dairy heifers across several smaller 100ha to 200ha farms.

Kikuyu is a problem, he reckons. While one grazier he knows has none as he spot-sprays it out, most do have it. His grazier has a high stocking rate which probably helps keep it in check – but the downside is it’s more of a struggle when dry or wet.

There is a dip in the animals’ weight gain in winter and summer but final targets are generally met, he says.

The grazier is very proactive about animal health with Peter paying for the vet. He’s happy with that as it’s in everyone’s best interest to keep the animals healthy, Peter reckons.

The grazier does the drenching and any other treatments, and Peter pays for the supplies. Should an animal get injured or become very sick it is sent back to the owner.

Peter has an annual contract and pays a set fee of $12 per animal per week, which doesn’t change throughout the year. He’s happy with the condition of the animals although there are weight checks in winter and again in summer. While there is some variation, they hit their targets in the end, he says.

“So the grazier is winning at the start when the animals are small and they have good pasture, and it gets a bit tougher when the animals are bigger and pasture growth struggles.”

His grazier does silage for feed over the summer, at no cost to Peter, and has managed to do that through most dry summers.

Droughts are becoming more common in the north and in those situations, they share the cost of any extra palm kernel, with Peter paying for cartage and the grazier feeding it out.

His grazier has a good name in the business, Peter reckons, which counts for a lot. He has heard of others telling owners to take animals home in a drought which is one of the worst things a grazier can do, he says, and will see them lose customers in the future.

“To take your money when the going’s good and then bail when the weather turns bad – that’s bad news and not on,” he says.

There is more work involved with young animals up to a year old, and while some graziers will ask for a premium to take on the younger animals, Peter’s grazier only accepts R2s.

Peter is keen on autumn calving, as once they are off the meal and into spring growth the animals don’t have that check early in their life, as spring calves do from poor pasture in the northern summers.

To avoid his cows mating when the pasture has slowed down in winter, he starts mating on May 23.

Matching graziers and farmers

Having worked as the Northern Service Manager for New Zealand Grazing for more than 10 years Ruth Marriott is an old hand at connecting dairy farmers with graziers.

While only taking on R1s and R2s is the preferred option for more than half the 20-odd Northland graziers Ruth has on her books, should a farmer want someone to take on their weaners she will likely have someone who is up for the job.

“Farmers in Waikato are more inclined to send the weaners off farm as soon as they can as their pasture is too valuable – they need it for their cows,” she says. “In Northland farmers seem to be more comfortable growing on the weaners and then sending them off farm as R1s.”

A farmer may contact the business looking to send 50 weaners out for 18 months, and Ruth will find them a grazier that will do that.

A grazier may say they have room for 200 head. Ruth will find perhaps four mobs of 50 animals and the grower only has to deal with her rather than 4 different owners. Ruth holds all the info on the animals including mating dates.

The capacity of the graziers goes from 35 animals, although that’s unusually small, she says, right up to 500 animals. Most graziers also run their own stock, be that beefies, sheep, or bulls.

Like Rachael and Brian, most of the graziers tend to use the grazing for cash flow.

“They get paid every month so this pays the bills, and they run their own animals that they may only get one or two cheques in a year for,” Ruth says.

Unlike Peter’s handshake arrangement, a written contract is always signed.

Ruth agrees the weather is a huge challenge in Northland with consistently dry summers, and this year saw a very wet winter.

Because the big summer dry is usual, it is expected to be covered in the normal contract. Only when it’s more serious – usually a government-declared drought – will they start applying drought subsidies, or going into negotiation on what’s going to work for everybody.

The wet winter this year saw some farms experience more than 1000mm of rain in four months and saw them go to farmers to discuss how to help these growers out, she says.

The owner is charged for animal health and the grower paid for animal health, so it is up to the grower to make sure the animals are well looked after, she says. This includes drenching although there is no stipulation on what drench will be used.

Overall Ruth finds the contracts work well. The LIC mature live weights for the animals go into the system, and that works as a target for where the animals need to be according to weight for age.

But the tougher northern conditions can see animals coming into the system 40 to 50kg behind target on average. Should that lower weight be similar across a herd coming in Ruth says they drop the target for the grower to meet so they would still get their bonus. They put an optimum line in as to where they should be grown.

“We don’t take the bonus off the grower as it’s not their fault the animals have been stunted,” she says.

While acknowledging Northland farmers experience tough conditions Ruth is less inclined to blame kikuyu grass – for lower weights.

Its not about kikuyu, she says, it’s about management and not being over stocked.

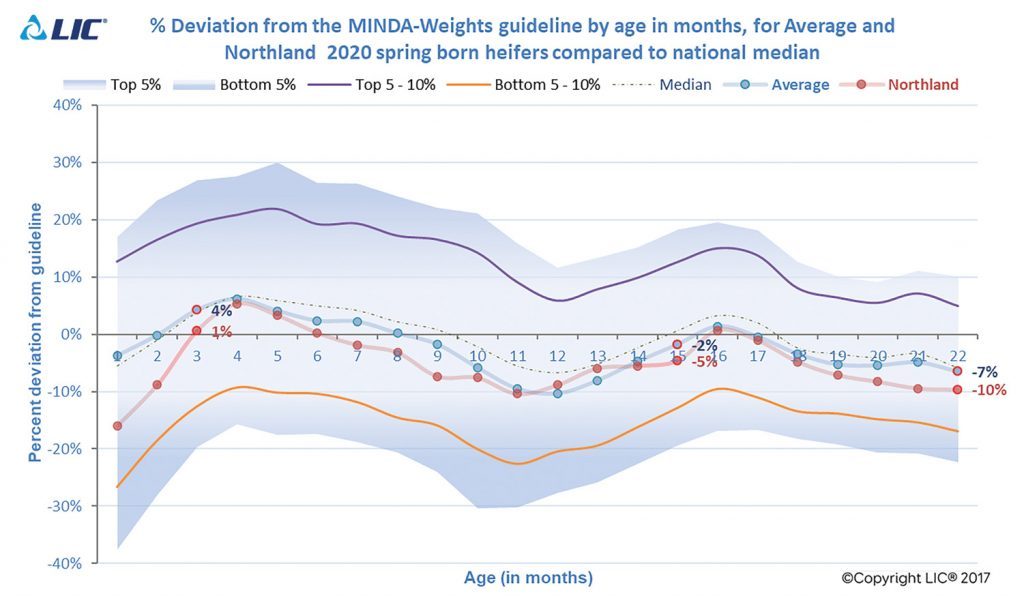

Heifer weights in Northland are consistently lower than other areas.

“If everyone carried a little less stock they’d make more money. Especially when you’re on a weight gain contract – the bigger you grow them the more money you get. It makes more sense to have less animals and grow them better.

“The dairy farmer gets a more productive animal, the grower gets paid better for it. Less stress on the land, less stress on the animal.”

It’s not Ruth’s job to tell graziers how many animals to carry, but her advice if they’re not hitting targets is to carry a few less and have an easier time.

Constant weight gain the target – but difficult

LIC Animal Performance Manager Steve Forsman says as constant a weight gain as possible is best with Northland having the worst results for this in the country. This is a reflection of tougher farming conditions in the north, he reckons.

The reasons for northern farmers to keep pushing to meet those targets in their heifers are important, he says.

He points to research done several years ago by Dr Rhiannon Hancock with the school of Agriculture and Environment at Massey University which showed being underweight before their first calving can have long-term effects on a heifer’s ability to get into calf throughout her lifetime, as well as reducing the amount of milk she will produce.