Anne Lee

Think of it like compounding interest, LIC stalwart Jack Hooper says when he explains how a good culling and breeding policy works.

“If you can keep removing the bottom end and shifting your average up, half of that gain is going to be passed to the next generation – it’s compounding effect,” he says.

Jack officially retired last year from LIC after 45 years on the job but now, as an occasional contractor to the co-operative, he’s still sharing his insights and providing advice to farmers around the country.

He’s worked alongside Lincoln University Dairy Farm’s (LUDF) management team for more than 15 years as they’ve successfully sought to build a herd capable of efficiently turning pasture into profit.

The process, he says has been double-ended.

Not only is the aim to feed high breeding worth (BW) replacements into the herd to lift its genetic potential you’re also pruning out the tail end using production worth (PW) as the guide.

“PW is the cornerstone measure for cow performance when selecting voluntary culls because it’s a measure of their lifetime productivity and efficiency,” Jack says.

The index is calculated initially using parentage production value information on protein, milkfat, yield, liveweight and now somatic cell count with the animal’s actual herd test information added in over time.

PW has been the starting point for LUDF’s culling decisions over the years with the first concerted effort to shift the herd make-up coming from the late Adrian van Bysterveldt in about 2005.

A number of the herd had been inherited from the university’s previous dairy farm and those animals were predominately Holstein Friesians.

Crossbred animals had been bought in too and Adrian had seen those cows producing well and remaining in the herd longer under the farm’s system.

He’d called on Jack’s input and together Jack and Adrian determined, from the herd’s performance data, that a F10-F12* cow was most suited to the system.

“Those cows were efficient at turning grass into profit and gave us the benefits of hybrid vigour,” Jack says.

To achieve that, F9 or higher cows were bred to high BW Crossbred and F8 or below bred to high BW Friesian.

With the breeding policy set, and a clearer understanding of what type of cow and herd the farm was aiming for, the culling policy could be set too.

Older low PW, F16 cows were more likely to be culled to move them out of the herd as higher BW, F10-12 heifers came in the herd.

LUDF farm manager Peter Hancox says of course empty rate is going to be a huge driver of how quickly a herd make-up can be shifted and culling used as a tool to both change cow type and take out lower performing, problem prone animals so efficiency and profitability can be improved.

The farm has never used induction and several years ago shortened its mating period to 10 weeks.

Its empty rate through to 2005, using 12 weeks mating had ranged from 16 -20%.

Culling empty cows and the change in herd make-up, a strong focus on improving six-week in-calf rates by hitting key body condition score (BCS) targets and achieving good heifer growth rates all helped to bring empty rate down to sit between 12-14%.

Over more recent years, empty rates have fluctuated from 15-18% with the latest pregnancy test results indicating a 16% empty rate for the 2019 mating.

Two shifts in farm policy since 2011 have created significant culling opportunities.

The first was to a sharper focus on growing and utilising more pasture, reducing bought-in supplement and matching stocking rate more closely to expected pasture production.

Cow numbers were dropped from 670 peak milked to 632 for the 2011/12 season with low PW, higher somatic cell count (SCC) and repeat mastitis offenders culled.

The result was a lift in average BW of the herd at the time to 114 and PW to 141 along with a lift in average production per cow from 395kg MS to 471kg MS and despite fewer cows more total milk production for the farm.

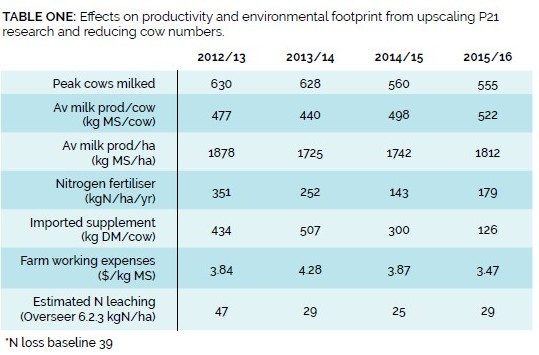

In 2014 another cut to cow numbers came when the farm’s management team decided to upscale the Pastoral21 research carried out at the Lincoln University Research Dairy Farm in an effort to push productivity and profitability further but reduce nitrogen loss.

The farm went from wintering 650 cows to wintering 580 and peak milking 555-560.

PW was again the go-to measure when coming up with a list of possible culls on top of empty cows. SCC, age, lameness, udders and mastitis incidence were also considered with fields such as SCC, age and calving date readily put in as fields on the culling report Peter pulls out of MINDA.

Again, the resulting lift in average production and higher number of more efficient converters of pasture into milk and profit meant productivity and profit were improved but importantly nitrogen loss as modelled by Overseer was reduced, thanks to less bought in feed and fewer cows.

Around the same time, Peter says a policy decision was made to try and rid the herd of the costly wasting disease, Johne’s Disease.

The whole herd is tested annually via a milk test taken from a sample from the third herd test each season.

In the first year, testing revealed 18 suspect, positive and high positive animals and following blood testing of those animals, 15 were confirmed as positive and culled.

The number testing positive and being culled each year has dropped steadily and in the last two seasons no animals have shown clinical signs.

“It’s a non-negotiable, if they’re positive they’re gone with the rest of the culls in early April,” Peter says.

Because of the nature of the disease and difficulties with the test picking up the disease in young animals it takes frequent testing and several years before the herd can confidently be declared disease free.

The need to buy in in-calf heifers after a poor synchrony mating programme result in 2018 has put the herd at risk of a new disease source.

“We’d hoped we would have culled it out within five or six years but I think it could take eight.

“It’s not a quick fix that’s for sure but it’s worth it,” Peter says.

Having clear culling priorities, using the culling guide and then being committed to the decisions is a must, he says.

“Empties and Johne’s positives are non-negotiables, then we run the culling guide after we’ve done the third herd test sorting the list on PW but looking at age, calving date and somatic cells.

“Last year we tested and found a couple of Staph. aureus cows. This season the bulk somatic cell count has been under 150,000 (cells/ml) and mastitis hasn’t been a problem.

“Through the season I ask the staff to note down any cows they think we shouldn’t be milking and the reason so they’ll get looked at too.

“This year we’ve got enough replacements coming through to voluntarily cull close to 40 – it could actually be hard to find 40 in the herd these days.

“It can be pretty hard to cull a high BW in-calf cow and that’s why you need a culling policy that you stick to.”

Jack agrees and says it’s important that the culling policy contributes to the overall herd improvement plan which is itself supporting and is consistent with the farm plan.

“Look at what’s top of the priority list when it comes to contributing to the profitability of the herd,” Jack says.

“SCC for instance or tight calving, each trait will have different values to each individual but PW is still going to be the foundation for sorting that initial list.”

They always rear more calves than final replacements needed and make a selection based on growth rates at weaning once DNA parentage results are back.

The calves reared are high BW with a portion of them from AI’d heifers and the rest from high BW cows.

Excess calves from the selection at weaning usually have a ready market but Peter says it’s been harder to sell culled high BW, in-calf cows as budget cows.

“We tried cutting our replacement numbers right back – as part of the aim to reduce overall footprint, but we ended up having to buy in animals and with Mycoplasma bovis and our aim to get Johne’s out of the herd we’ve gone back up to rearing 25% replacements,” Peter says.

Rearing enough replacements to give choices when it comes to culling is imperative, both Jack and Peter agree.

“If you have no choices you have no control and its important to be in control of decisions about herd improvement otherwise, you’re treading water,” Jack says.