Taking on a long lease for a family farm at the top of the South Island after years working overseas means a couple are free to make decisions. Story and photos by Anne Hardie.

Leasing the family farm near the northern tip of Golden Bay has given Ellie Miller and Pax Leetch the opportunity to do things their way.

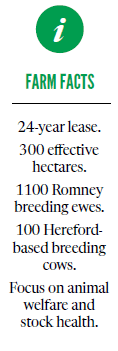

The Miller family farm, Nguroa, lies near the Kaihoka Lakes in Golden Bay and bounds several kilometres of bluff-edged coastline, culminating in the sheer sides of Lunar Rock above a patch of beach. Sand-blasted hills encircle patches of wetlands and about 220 hectares of mostly regenerating bush on steeper slopes and 10ha of radiata pine trees. That leaves 300 effective hectares of the 520ha to run 2269 stock units made up of 1100 Romney ewes, 100 beef-breeding cows and replacements.

Six years ago the couple approached Ellie’s parents, Peter and Marjorie, about leasing the farm. Peter and Marjorie were in their mid-70s at the time and still working on their farm. They were reluctant to give that up. Both generations still live on the farm and Ellie’s parents buy some of the weaned calves to finish on a productive block they still farm near Collingwood.

Pax says Peter and Marjorie were hard workers and put their life into Nguroa. They took on a well-cared for, productive farm.

“It has been fantastic leasing,” Pax says. “Being free to make the decisions we see fit…it’s very freeing.”

The farm is in a family trust. Ellie’s siblings wanted the farm to stay in the family, but didn’t want to farm it themselves. A farm consultant worked out a fair lease agreement, basing it on the Federated Farmers lease contract, which Ellie says is nice and simple. They pay $22/su and have a 24-year lease divided into three-year terms with seven rights of renewal.

Pax says they were keen to have surety that works better for the farm. They will come out of the 24-year lease with stock and plant, so will need to establish a nest egg somewhere else by then.

He says sometimes leasing is to the detriment of the land because lessors want to wash their hands of obligations to that property because they’re not running it. Lessees are always looking at the next thing.

“So no-one is looking at the property like they own it.”

This way, they have a decent timespan to invest in the farm themselves. Such as a reticulated water system that’s waiting on the sideline to be installed when they have time. Peter and Marjorie will pay for the tank but Pax and Ellie will pay for the pipe, troughs and installation to get water to paddocks instead of relying on streams.

Pax says the water system will be a game-changer for them as they will be able to graze all paddocks more efficiently.

Animal welfare governs

On the farm, animal welfare governs the business, from stock numbers to the way they handle the stock. When they began leasing the farm, Ellie and Pax dropped ewe numbers by 100 and began selling calves at weaning to take pressure out of the system.

They now have more feed through winter to feed stock and into spring when the wind cranks up. It stops the spring flush and it helps to make their goal more achievable: to run a simple, profitable operation well, purely on grass.

The ewe flock has 40 years of Wairere Romney breeding and the couple sees no reason to introduce new genetics. They tail 150–155% following an intensive lambing beat, which is part of their animal welfare philosophy. Their goal is for 10% or less wastage, and they are close to that most years.

“We wouldn’t be getting that lambing percentage if we weren’t doing that,” Pax says.

He thinks they are adding about 10% to the lambing percentage.

The mixed-age ewes usually scan 180–185%, while the two-tooths scan 160–170% and they don’t want any higher. This year, scanning results were down and Ellie and Pax suspect there was subclinical facial eczema in many of the ewes as they saw clinical signs in the lambs. It’s not usually a problem, probably due to the coastal winds keeping the spore count down. This year they enjoyed a calm autumn and they think they paid the price for that with facial eczema. At scanning, the ewes dropped to 165% and the two-tooths were 148%.

Hoggets weighing over 42kg in autumn go to the ram which is about half of the hogget mob. For the past three years they have lambed the heavier hoggets and this year they scanned 92%. In the past, other classes of stock were prioritised over the hoggets through winter.

Pax says they now do a better job of their hoggets since they began running half of them with the rams. If they get a hard year and the hoggets are compromised, they will give hogget-lambing a miss.

Hoggets are mated to the Romney rams along with the maternal mob of ewes. A terminal mob of ewes is mated with Suffolk-Texel rams. After the first cycle, everything goes to the terminal rams and the black faces make them easily recognisable.

From scanning, the mixed-age and two-tooth ewes run as one mob and are rotationally grazed around the farm until they are set stocked for lambing. Triplet mobs get the better paddocks and they split the others into a mixed-age twin mob, mixed-age single mob, two-tooth twins and two-tooth singles.

Bluffs and bush give shelter

Lambing begins from September 5 and the hills, bluffs and bush provide good shelter.

From all the mobs, they pick up a lot of lambs, but after mothering-on most of them they end up with about 15 that Marjorie rears.

Stock rotations begin again a couple of weeks after tailing.

Pax and Ellie are disappointed with lamb growth rates. They have enough feed through lambing, but don’t have that spring flush of feed to get the lambs growing. The farm is not suitable for crops to help finish them. About 10% of lambs go prime at weaning before Christmas and the couple wants to lift that. They don’t want to carry store lambs through the next winter, but they can be hard to quit.

“We struggle a bit with store lambs because we’re not big numbers and if we’re dry, then Nelson is dry too. We need to piggyback with someone else to move them,” Pax says.

Those lambs that do head to the works prime get a premium through Alliance’s special-raising claims that require lambs to be free of antibiotics and raised solely on pasture.

Pax confesses he’s a bit of an idealist. He doesn’t like to use antibiotics if it can be avoided, isn’t keen on drench and prefers not to spray.

“I’d like to farm without them, but we aren’t able to do that in our current system.”

Pax and Ellie have opted to sell calves at weaning so they no longer have the cost of buying in balage to winter weaned calves, and it enables them to feed stock better through winter and spring.

Initially, they sold the weaned calves through the yards at Brightwater, nearly three hours drive away. But it didn’t sit well with them. Half came back over the Takaka Hill to buyers and they didn’t feel good about leaving their stock in saleyards.

“We didn’t enjoy having them in the saleyards at all,” Ellie says. “Once they leave here you don’t have control over their welfare any more.”

They now sell the weaned calves at an agreed market value within Golden Bay, with some going to Ellie’s parents for their block near Collingwood, a few to Pax’s parents and the rest to another farmer down the coast.

The Hereford-based cows have Angus genes through them as well, plus a bit of Shorthorn from the past, and are divided into two herds at mating. The A herd is run with Hereford bulls and the B herd and heifers run with Angus bulls.

Copper deficiency in the herd became obvious when 7–8% of cows were empty and some were gaining an orange hue to their coats. Initially they were given two injections of copper a year but liver tests at the works showed they were still deficient and they’re now given three injections a year. This year the farm reached 98% in calf and the couple hopes they have the deficiency covered.

Fertiliser ‘part of the arsenal’

A few years ago Pax and Ellie had concerns about the animal health on the farm, such as bad feet in the ewes and mastitis in the cows. Culling has helped, but improvements have also been made through changes in their fertiliser regime.

A few years ago Pax and Ellie had concerns about the animal health on the farm, such as bad feet in the ewes and mastitis in the cows. Culling has helped, but improvements have also been made through changes in their fertiliser regime.

For the last two years they’ve been following the Albrecht-Kinsey approach to fertiliser, and feel they are seeing better animal health as a result.

Though the sandy country gets hit hard through summer with drying winds, the farm usually gets good grass growth through autumn which sets it up for winter. Being coastal, the farm usually continues to grow some grass through winter as well.

About 40% of the farm is covered in regenerating bush.

Pax says the Beef + Lamb NZ greenhouse gas calculator shows the farm is sequestering more than it’s emitting. Yet through the New Zealand Emissions Trading Scheme their 220ha of regenerating bush will not count. He says tunnel-visioned government regulations focusing on just carbon could make farmers financially better off by razing some bush areas and planting pines. Pax and Ellie have no intention of doing that, but Pax says regulations for greenhouse gas emissions need to have a holistic approach that looks at the wider picture.

Keeping things quiet

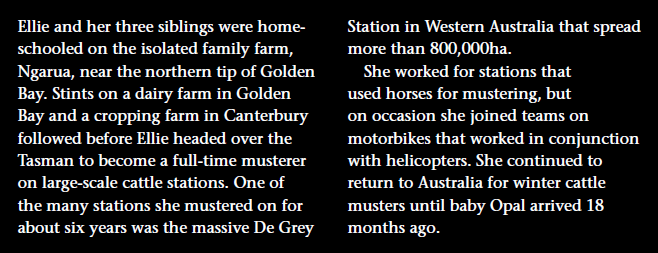

Cattle work on Nguroa is usually carried out on horseback, partly because of Ellie’s passion and background with horses, but also to handle stock with as little stress as possible. This keeps the cows quiet in the paddocks so calves can be tagged at birth and paired with their mothers.

Cattle work on Nguroa is usually carried out on horseback, partly because of Ellie’s passion and background with horses, but also to handle stock with as little stress as possible. This keeps the cows quiet in the paddocks so calves can be tagged at birth and paired with their mothers.

In Australia, cattle were sometimes worked from outside the yard and Ellie says it often meant using minimal movement to move beasts in the required direction. They use the same stock handling principles with their sheep in the yards – moving them through the race quietly to avoid them crashing into gates and piling up.

Ellie met Pax in 2013 when he was working for her parents on Nguroa. He’d grown up on a small farm in Golden Bay, been a cadet at Smedley Station and had worked as a shepherd. After coming back from overseas he worked as a fencer and then spent three winters on a revegetation project for a Mongolian gold mine. In 2012 he found his niche at Nguroa.

Since giving up her full-time mustering stints over the Tasman and feeling a little homesick for the lifestyle, Ellie has been starting horses for clients through summer, starting one horse a month. The horses get exposure to stock work and hill country through their first month of riding. She loves the work and it provides another income stream for the farm.

One day each week they have a casual employee, Josh van der Stap, help out with jobs on the farm, which is usually fencing. Sand and salt blasts take a toll on fences and in exposed areas the fences only last about 10 years before they succumb to rust. Old fence posts are half-buried by sand that’s blown over the farm through the decades.