Anne Lee

As farmers work their way through how they can limit nutrient losses to water they’re now having to come to grips with limiting greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions to air.

The good news is though – in many cases the two can go hand-in-hand and there need be no major impact on profitability.

DairyNZ senior scientist Dr Dawn Dalley and AgResearch farm systems and environment scientist Dr Robyn Dynes told the South Island Dairy Event (SIDE) that while GHG reduction targets haven’t yet been set for farmers they need to start understanding what drives their emissions and what they can realistically do to lower them.

The Government has signed up to the Paris Agreement on Climate Change committing to 30% reductions on 2005 levels by 2030 and 50% reductions on 1990 levels by 2050.

It is possible to reduce nutrient losses and GHG emissions and be highly profitable but they warned farmers to work through the effects of any system changes carefully to ensure they achieved the outcomes they wanted without creating unexpected consequences.

Cutting nutrient losses by building stand-off pads, for instance, could help reduce nitrate losses but if that meant a significant increase in the amount of stored effluent, methane emissions could go up.

‘Pollution swapping is a risk so it’s important to take both the losses to water and air into account when you’re thinking about how you’re going to achieve loss limits.’

“Pollution swapping is a risk so it’s important to take both the losses to water and air into account when you’re thinking about how you’re going to achieve loss limits,” Robyn said.

Having a good understanding of loss limits and timelines was essential as was having an understanding of the options available, Dawn said.

“Those options have to be assessed against the overall farm performance and efficiency and have to be tailored to meet the goals of continued business viability as well as meeting nutrient and GHG loss expectations,” Dawn said.

Farmers can see their farm’s estimated emissions in their Overseer files, represented as tonnes of carbon dioxide (CO2) per hectare.

The average New Zealand dairy farm emits 11.5 tonnes of CO2 equivalents/ha with fertiliser and transport included in that figure.

About 80% comes from methane.

Methane emission reduction options centre on reducing feed inputs, adjusting stocking rates and reducing replacement rates.

To reduce nitrate leaching farmers should look first at how they could lower their nitrogen surplus.

Farm gate nitrogen surplus is the difference between nitrogen inputs (mostly fertiliser nitrogen and nitrogen brought in as supplementary feed) and nitrogen outputs (mostly milk or exported feed).

Lowering nitrogen fertiliser use, improving the timing of application to when plants can take it up most efficiently and reducing the amount of brought-in feed can reduce nitrogen surplus.

Nitrogen use efficiency is the ratio of nitrogen exported from the farm per unit of nitrogen inputs.

Improving it through higher genetic merit cows, for instance, can help but on its own better nitrogen use efficiency may not always lead to less nitrogen leached.

Other ways to improve nitrogen use efficiency include cutting back replacement rates, better timing of nitrogen fertiliser and better pasture and feed utilisation.

• Improve the efficiency of

converting N to product

• Reduce N inputs

• Reduce milking cow numbers in

autumn

• Capture surplus N and redistribute

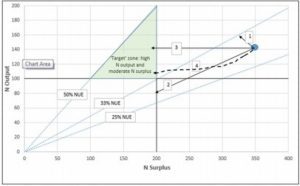

Figure 1 shows the top left triangle as the optimum or target zone – high nitrogen output and a moderate nitrogen surplus.

If the farm is operating at high nitrogen surplus and high nitrogen output increasing nitrogen use efficiency alone (1) won’t move it into the target zone.

Reducing nitrogen inputs by cutting fertiliser and/or cutting the amount of brought-in feed without any increase in nitrogen use efficiency would take it in direction two.

It’s only through a combination of options one and two that the farm moves into the target zone.

In practice achieving such a big increase in nitrogen use efficiency would be hard to achieve and the trajectory is more likely to be four – with some loss of production. But lower costs of production may hold profitability.

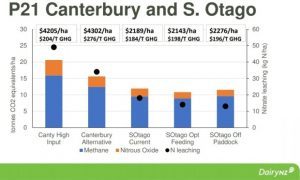

Profitability analysis from the Pastoral 21 studies found profitability could be maintained with system changes to reduce nitrogen leaching and that in most cases GHG emissions also dropped. (Figure 2)

The off-paddock system had an increase in GHG emissions due to increased effluent volumes stored.

Go to www.dairynz.co.nz/media/5787573/otago-site-summary.pdf to see a summary of the Otago system differences.

The Canterbury high-input system had a stocking rate of five cows/ha, used 350kg N/ha fertiliser and fed 700kg drymatter (DM)/cow of brought-in supplement.

The Canterbury alternative system ran 3.5c/ha, used 150kg N/ha fertiliser and fed 50kg DM/cow supplement.

Dawn suggested farmers began looking at additional metrics to assess their profitability in light of nutrient and potential emissions restrictions, particularly when they were assessing systems changes.