Farm dam safety is subject to regulations being assembled by government and councils, upsetting farmers. Story: Glenys Christian Photos: Alex Wallace

Kaipara Flats sheep and beef farmer, Simon Withers, was surprised to get a letter from Auckland Council last year about new dam monitoring regulations. It was the first the retired accountant had heard of the proposals and he was immediately concerned they heralded yet another set of compliance requirements foisted on farmers.

It was also of concern that the council had clearly flown over his farm because included with the letter was a copy of a photo of the dam taken from the air.

“It will set the Groundswell movement off again,” he says.

The dam photographed is one of 15 on his farm north of Auckland, which he believes attention had been drawn to because of a long-reach excavator being used to clean it out.

“That made it more obvious,” he says.

The dam safety regulations, once passed into law, will be monitored by local authorities using a registered engineer whose fees will be payable by farmers around the country.

In the letter he received Simon was asked for details of the capacity of all the dams on his farm as well as a description of what they were used for. But he argues that as they were there before he bought the farms he has no way of knowing when they were built, their height and the amount of water they contain.

Included was a formula of how to calculate capacity and he was also asked if the dams allowed fish passage. But he believes gathering such information would involve costly engineering fees.

He was brought up on a dairy farm out of Paparoa, on the west coast of lower Northland. “I had a bent for figures but I always liked farming,” he says.

So after completing a Bachelor of Agricultural Science at Massey University he bought into an accountancy practice in Warkworth, only recently retiring after 51 years as a chartered accountant.

In the late 1970s he bought his first farm of 28 hectares in Warkworth where he ran heifers, eventually selling that to become eight lifestyle blocks. With a desire to farm on a larger scale in the 1980s he bought 65ha at Kaipara Flats, west of Warkworth.

“It was good land with a reliable rainfall,” he says.

“But it had had no fertiliser for over 20 years. There were broken buildings and fences and plenty of old trees and weeds.”

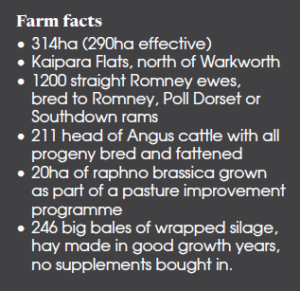

He improved it over the next 15 years, while fattening heifers and steers, before “taking the plunge” and buying three separate blocks and selling the first farm. While one was steep and undeveloped the other had about 50ha of good flat land which needed to be drained and cleared of macrocarpa. So over the past 40 years he’s built up a good-quality fattening farm of 314ha of which 290 is effective, fencing off bush stands on the way through

He now runs 1200 straight Romney ewes, mainly from Wairere, along with 12 Romney and eight Poll Dorset and Southdown rams. Lambing is later than usual for the area in late July or early August with averages of about 140%.

About 270 replacements are kept with the rest going to Affco from late November then monthly through to June or July at about 18kg.

He also runs 211 head of Angus cattle, including 90 heifers with all progeny fattened. While calving used to be in August, that’s now moved to September. The only stock bought in are 37 two-year-old steers from the Peria Saleyards in Northland as weaners and 13 rising two-year-old heifers.

With kikuyu through all his flats he’s embarked on a pasture improvement programme, spraying out twice then growing short-rotation ryegrass for a couple of years. For the past two years he’s trialed Raphano brassica.

“It’s the only thing that’s as green as the kikuyu,” he says.

While the economics might be marginal, the 20ha he’s growing has certainly helped fatten his lambs.

“It doesn’t grow too high and if it’s sown at the end of October or the start of November the lambs can be on it by mid-January for quite a long period.”

He’s tried chicory but that crop failed through lack of rain, and while plantain did quite well there were issues with weeds such as black nightshade.

Wrapped silage is made with 246 bales being taken off this year. Hay is made in the years where there’s good grass growth for the bulls, but none was made last spring and summer. No supplements are bought in.

About 20 tonnes of nitrogen is applied on the flats where the summer crops will be sown. Maintenance fertiliser of 60t a year of sulphurised super 10 goes on with molybdenum added for the first time last year. Lime goes on every three years and soil testing is carried out every two years. The pH levels range from 5.9 on the hills to 6.4 and Olsen P levels of 35 to 79.

Wrote to the council

Simon initially ignored the letter about dam monitoring but then wrote to the council. Its reply drew his attention yet again to the upcoming safety regulations saying he and other farmers would be given a two-year period during which there would need to be engagement to monitor dams covered by the legislation.

The council wanted information about his dams well ahead of time, saying any dam more than one metre high and containing 40,000m3 or 4m high and containing 20,000m3 of water would need to be monitored annually, which Simon says would just incur more engineering fees.

“It’s just another regulation they are trying to load on farmers,” he says.

“It’s almost impossible for the farmer to tell what the cubic capacity is, where the dam height is measured and how the water it holds is calculated.

“Water is hugely important to be able to farm properly and animals rely on it.”

While he was told when he bought the farm he would have no worries about water after 10 years he says he noticed the summers getting warmer.

“So I built a good quality dam in the front paddock,” he says.

Water is pumped from there to a header tank, and gravity fed to 24 paddocks.

“It took three months to build and was finished in January. And that summer the stream went dry, meaning I wouldn’t have had water for my stock. There have been a number of years since where I’ve patted myself on the back for that.”

The dams already on the farm have been cleaned and dug out to improve both quantity and quality of the water.

“They’re generally cleaned every few years of weed and rubbish,” he says.

Simon believes farmers are being targeted once again by the proposed regulations.

He knows of one other local farmer who received a letter similar to the one he did, and has passed on his concerns by writing to National Party leader, Christopher Luxon.

“This will add flames to the Groundswell movement.”

He attended the Groundswell Howl of Protest in Orewa last year with his farm manager, Josh Jackson, and his two huntaways.

“All the dogs there were barking furiously when instructed,” he says.

“It was fantastic. Even the dogs were protesting.”

‘It caused some angst’

Federated Farmers’ national policy manager, Nick Clark, says a number of the farmers who received the letters about upcoming dam safety regulations from Auckland Council were not happy.

“They felt they were intrusive,” he says.

“It caused some angst.”

Farmers with a number of dams on their farms believed they would have to supply details for all their dams, rather than just the large ones exceeding the threshold to be set by the new regulations. Auckland Council was the only one so far to write to farmers about the new regulations, which saw the matter referred to its rural advisory group which meets regularly to discuss issues impacting the agricultural sector.

Clark, who is the federation’s representative on a technical working group set up to give guidance on the dam regulations, says there is no ballpark figure as to how many dams around the country they might capture. Regional councils would know the number of dams they had consented in recent years but not those predating their establishment. And he says there is no mention of fish traps in the draft regulations.

Auckland Council’s manager, proactive compliance, Adrian Wilson, says it sent letters to 177 properties in July 2021 regarding dams on their land.

“What dam owners will be required to do to comply with the regulations will depend on the dam’s height, capacity, and potential for downstream impacts,” he says.

The new regulations would apply to any dams four metres or higher with a volume of more than 20,000m3 or eight Olympic-sized swimming pools, or greater, or 1m or higher with a volume of more than 40,000m3 or 16 Olympic-sized swimming pools, or greater.

Landowners will also be given information on how to measure and calculate the size of their dams.

“It is our opinion that the majority of those who received letters will not have to do anything to comply, as small stock watering ponds and other small farm dams are most common and are unlikely to exceed the above criteria,” he says.

But the council had a duty to ensure property owners were aware of the changes to legislation and so had sent the letter to a small cross-section of members of the federation.

The Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE) says in July and August 2019 it consulted the public on a proposed regulatory framework and following feedback policy decisions were agreed in March last year.

It’s drafting the regulations and expects to finalise those in the first half of this year. There’s then a two-year period until they come into force giving dam owners time to check whether their dam is big enough to be included in the regulations. During that time MBIE says it will support dam owners to check whether their dam will be included and, if they do, how to meet their obligations, with more resources being made available over the rest of this year.

Farmers will have a further three months to classify the potential impact of the dam’s failure on people, property and the environment. That will confirm whether a dam has a medium or high potential impact with owners having one year to complete a dam safety assurance plan for high potential impact dams and two years for medium potential impact dams.

The intent of the regulations is that small or remote dams are either excluded from the regulatory framework or most of the ongoing obligations. Structures such as stock drinking ponds, irrigation races, weirs and small ‘turkey nest’ dams would not be included in the regulations and MBIE expects most agricultural dams would face no or few regulatory requirements. It will produce a tool which should be available by the middle of the year to help dam owners calculate their size and whether it is big enough to be included in the regulations.