Reducing cow numbers has helped a West Coast couple cope with changing weather patterns. By Anne Hardie.

Dan and Kate King always thought they would need a 200-cow farm to be viable, but they have been able to reduce their herd to 155 at peak milking while increasing per-cow production to take the pressure off the environment, cows and people.

It is part of their solution to adapting to wetter springs, prolonged dry summers and the unpredictability of the weather which are the new normal on their 73-hectare effective dairy farm just north of Reefton on the West Coast. In early February this year, more than 200mm of rain was dumped on the farm in a 24-hour period. Then March was particularly dry and they were irrigating a month later than usual. Such is the fickleness of the climate now.

The Kings made that much-sought-after step into farm ownership in 2014 on the eve of Westland Milk Products’ $4.95/kg milksolids (MS) payout. A severe drought gripped the region in their first summer and their cows survived on 100% supplements for six weeks. But they survived.

The Kings made that much-sought-after step into farm ownership in 2014 on the eve of Westland Milk Products’ $4.95/kg milksolids (MS) payout. A severe drought gripped the region in their first summer and their cows survived on 100% supplements for six weeks. But they survived.

Being naturally prudent, working with conservative budgets and selling their cows at the peak of the market to buy the farm meant they weren’t mortgaged to the hilt and they were reasonably comfortable financially. To the point they bought a pivot going into their second year to irrigate 27ha and ensure they would have some grass during the next drought. They barely used the pivot for two years, though they have since had four seasons where it has just about paid for itself.

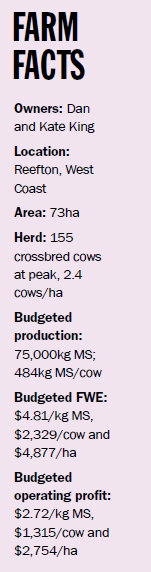

Drier summers have followed wetter springs and the Kings realised they needed to farm for the extremes. When they bought the farm it was 66ha and they were peak-milking 210 cows at 3.2 cows/ha. Since buying the farm they bought a 15ha block around the house and then last year they sold the house and 7.7ha so they could build a new house on the farm. This year they wintered 160 cows, which gives them 155 Friesian-cross cows for peak milking. Adding young stock up to nine months of age on a 4ha block gives them a stocking rate of 2.4 cows per hectare on 73ha.

With fewer cows, they are now focusing on increasing production per cow which will also dilute costs. This season they are budgeting on a total production of 75,000kg milksolids (MS) which is 484kg MS/cow and 1,014kg MS/ha. Their three-year average is 467kg MS/cow and 1,031kg MS/ha.

On the other side of the budget, costs keep climbing for farmers, but farm working expenses (FWE) in Dan and Kate’s 2022-23 budget is only 8% higher than it was two years ago. A recent analysis by consultants AgFirst showed FWE across the industry had risen by 36%. Last year they budgeted on FWE of $4.45/kg MS and costs across the industry soared, so the actual figure was $4.70/kg MS. This season they are budgeting on $4.81/kg MS which will work out at $2329 per cow and $4,877/ha.

Higher payouts have offset increasing expenses and last season they were well ahead of their budgeted operating profit of $2517/ha with an actual $3187/ha. This season’s budgeted operating profit is $2754/ha.

Dan and Kate say higher cow numbers would result in higher FWE and in a good year without extreme weather events would also produce a higher profit. But they want their business and farm system to have more resilience and fewer cows is part of their plan to achieve that goal.

“When we had higher stocking rates, you only needed a bit of a drought or wet spells and the wheels fell off,” Kate says. “By dropping cow numbers you may miss a bit of production when conditions are good, but you have a bit more resilience in your farm system.”

Dan says lower cow numbers enable them to carry higher pasture covers. During wet spells the cows squash some of that grass beneath them which helps to reduce soil damage. Climate change and weather extremes that may inflict on dairy farms means cows will need to be fully fed so they are content and not trashing the ground, with shelter such as trees for protection, Kate says. She does not discount the possibility of dropping cow numbers even further, while ensuring they have plenty of balage in the system to keep cows fully fed.

In the past they have liberally used palm kernel. Last season (2021-22) they doubled their use of palm kernel in their budget due to a lack of works space for culls going into winter, a wet winter and spring and higher forecast milk prices. They brought 371 tonnes of palm kernel on to the farm which worked out as a profitable decision due to the final payout and pasture challenges through summer and early autumn.

This season they had 40t left over and contracted a further 100t which was fed out through winter. They have replaced some of the palm kernel on their budget with hay to reduce costs. At about $100 a large bale, they can buy in a lot of hay compared with palm kernel which had risen to $505/t landed.

The hay was fed to the springers on grass to fill them up and keep them contented. The milking herd will still average 2kg palm kernel per cow per day unless they are mowing in front of the herd and don’t need it, or feed is tight and they will feed up to 4kg if needed. On top of imported supplements, they make 180-or-so bales of balage from genuine surplus which is set aside for the milking herd. When grass growth rates are really high, they carry out pasture monitoring every four to five days. Surplus is managed by taking regular, light cuts of balage. The main focus is to feed more grass into the cows.

“If we have enough grass, we’ll try to feed them just grass and mow in front so we can offer them 22kg pasture per cow per day,” Dan says. “We’ve done it before sporadically and we generally have to top through spring anyway because you can’t control it without taking a big hit on production. So we’ll try and be proactive and mow in front and try to keep it in better quality.”

They plan to begin pre-grazing mowing early, before pasture quality deteriorates. Regular feed budgeting is carried out throughout the year with the spring rotation planner used when appropriate. Pasture cover is then assessed every seven days using a C-Dax pasture meter and that data is used to update the feed budget. That information is then used to manage supplementary feeding levels, harvesting and cropping decisions. Cows are milked twice-a-day from the beginning of the season and transition to 3-in-2 milkings when they average 1.8kg MS/cow/day, then once-a-day at about 1.5kg MS/cow. That way they can adapt to whatever the season throws at them.

Wet springs have made fertiliser applications challenging and Dan says they plan to be more proactive so they can pounce when weather and ground conditions enable them to spread. The changing climate has reduced the opportunities to get fertiliser on through spring. He says they need to be on their toes to grab those opportunities because it is too easy to miss them.

In the pasture itself, they are searching for the right mix for their system but have not found it yet. They trialed bought mixes but found many include annuals that then leave the pasture sparse, or sunflowers which the cows find unpalatable. Last year was wet and that highlighted the need to have the right weather conditions when sowing to avoid weeds grabbing an opportunity to take off. Last year nightshade was a problem and they could not spray a diverse pasture mix without wiping out some of the species. When they sowed their 6ha winter swede crop with 50% swede and 50% of a diverse pasture mix that was designed to grow with a winter crop, they felt short changed. They weighed some of the resulting crop and worked out they grew about 10t of swede and about 1t of the diverse mix and that left them thinking they might as well have stuck with just swedes. They had added the diverse mix with a kale crop as well and Kate says they could not justify spending the extra money on the diverse mix if it did not pull its weight in the crop.

“We believe in diversity, but we need to design our own mix,” she says.

One of the reasons for trialing diverse pasture mixes with both their winter and summer crops is to reduce cultivation and spraying to achieve best environmental practice, but it is definitely a work in progress. When they tried direct drilling for their diverse-mix winter crop, the results showed they grew 11t/ha. This season’s winter swede crop was a full cultivation HT swede that was precision planted and resulted in 20t/ha.

Planting shelter around the farm has become another priority on the farm, with animal welfare in mind. Alongside the yard into the dairy they planted pittosporums four years ago to provide some shelter for the cows as they wait for milking and those trees are already doing their job.

Part of the lane has been enlarged as an emergency standoff area during wet weather and they have planted pittosporums along its length that they have grown themselves. That is because they found it hard to find trees to buy – and it is cheaper.

Around the boundary of the farm and alongside every paddock they have begun planting Balsam poplars and Italian alders to help moderate the wind speed during cold, wet weather and also provide shade during the heat of summer. They chose those two varieties for their deep rooting systems which will help them survive droughts and stop them competing with grass. During winter they double fenced the boundary and planted Balsam poplars every 15m.

Health and safety is taken seriously onfarm. No-one visits without being inducted, signing in and confirming an induction process has been followed. Posters and protocols are displayed on the outside of the dairy, with contacts so visitors can contact Kate or Dan at any time. If they have not seen visitors leave the farm, the visitor – usually a contractor or relief milker – has to text or phone them to say they have left the property. Kate says it is essential that visitors let farmers know when they leave in case they have an accident or medical emergency at the back of a farm where they may lay for hours before anyone finds them. The sign-in book and a chemical information sheet is kept in a letterbox beside the dairy. That way, emergency services know what chemicals they may be tackling if there is a fire. Kate says they picked up many of their ideas off their peers and continuing to network is one of their methods of learning new farming and business ideas. They will be open to all ideas about balancing their budget in a changing environment and working out the best stocking rate for the extreme weather periods.

Financial resilience the key

Dan and Kate King had been a couple just over a year when they took up a 23% lower-order sharemilking contract with their newly combined goals firmly set on farm ownership.

Dan had grown up on a family dairy farm in South Westland where he learnt early on about business. As a school kid, he bought his pet calves, paid for the meal, leased the adult cow to his parents and he would own its calves.

“Seeing the way animals could multiply got me interested in farming,” he says. “But Mum and Dad tried to talk me out of it because they had been through all the challenges dairy farming can throw at you.”

Undeterred, he left school to work in the dairy industry and one of his bosses allowed him to graze 50 weaned calves he had bought as part of his contract. In return for free grazing, his boss milked them through their first year in milk. That same boss then bought a 200-cow farm and Dan was offered a manager’s position. As an incentive, Dan was able to swap the in-calf heifers for a 5% share in the farm. Kate, on the other hand, grew up in town and after failing maths at school two years in a row, headed to Telford at 17 because she had always loved being on the farms of family friends. Dan was at Telford a year earlier for a Diploma in Rural Business. Unknowingly, they followed each other around the South Island through their careers. In between, Kate – the girl who had failed school maths – headed to Lincoln University and completed a Bachelor of Commerce (Agriculture).

Kate was working on the West Coast when she met Dan who was still managing the farm near Gore. A year later they took up an offer of a lower-order share milking role on a 500-cow farm on the Coast. At the end of the three-year contract the farm owner bought a neighbouring farm, giving Kate and Dan the opportunity to sign up a three-year 50:50 sharemilking contract on the increased herd of 870 cows. That first year they owned 150 cows and leased the remaining cows. Through $6, $7 and $8 payouts over three years, they were able to pay off considerable debt and buy all of the leased cows.

“We had good timing and the cashflow was extremely good for us,” Dan says.

Eventually they owned about 800 cows and sold 500 fully recorded cows to buy the 66ha farm near Reefton which has increased to 73ha.

“We thought going from 870 cows to 200 cows would be a walk in the park,” Kate laughs. Their eldest child, Sam, was two and Kate was pregnant with their daughter, Lizzie, when they accepted they needed a relief milker to help them out. When Lizzie was three and payout dropped to $3.80, it went back to just the two of them on the farm.

They now have one casual employee who works six mornings a week through August and September and then every second weekend through the season. For the past three years they have not carried an overdraft and rather than use higher payouts to pay off more of their loan, they have chosen to build a cash buffer. If things get tough, Kate says they can always get an overdraft then, rather than rely on it now.