The outbreak of foot and mouth disease in Indonesia has raised alert levels in New Zealand. By Anne Hardie.

Biosecurity measures at the border will hopefully continue to keep foot and mouth disease (FMD) out of New Zealand, but farmers also need to be on the front foot with their own biosecurity practices. Because sometimes, like Covid-19, the problem can be in the country and circulating before we know it.

That means keeping a diary of all visitors to the farm and if you have staff or family returning from countries that have FMD and they have been around animals, they should not have contact with animals in NZ for a week. That’s not just Indonesia which has the latest outbreak, but numerous parts of the globe including countries in Asia, Africa, the Middle East and South America.

An estimated 77% of the global livestock population live in countries with FMD, so it gives some idea of its prevalence and the airways are busy again with travellers.

Ministry for Primary Industries chief veterinary officer, Dr Mary van Andel, says biosecurity practices on farms are an insurance so that if the disease gets into the country, it doesn’t spread or at least spreads slowly.

“We would hope we would find the first case of FMD in New Zealand, but we could never be sure.”

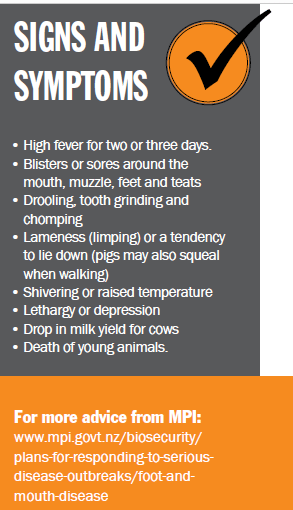

It is one of the reasons farmers need to know the signs of FMD and raise the alarm to get it checked out as soon as they are suspicious. Dr van Andel acknowledges farmers will be fearful of doing that, but every day delayed is another day where farms can get infected.

Traceability is key and since Mycoplasma bovis there has been a marked improvement in NAIT recording on NZ farms which, she says, will be essential for tracing animals if there is a FMD outbreak. It is not perfect yet though and she says some people find it difficult to comply with the NAIT scheme, for whatever reason.

Farmers’ own biosecurity measures for a potential outbreak of FMD – or any other diseases that may slip into NZ – should start with a simple onfarm biosecurity plan that is updated regularly and familiar to all staff.

The visitor diary should record anyone coming onto the property so that should an infection arise, it is easy to trace people movements for the weeks leading up to its discovery.

Dr van Andel says every farm should have a policy all the time that no dirty boots are brought on to the farm because of the potential to introduce diseases from other properties. The same applies to equipment and machinery used on different properties and there should be a ‘clean slate’ policy between properties.

All employees should know the rules and she says everyone should be respectful to other farmers’ biosecurity when going to a property.

One of the most dangerous ways of spreading the disease is through animals and meat products imported from countries with FMD. Feeding food waste that includes meat products (swill) to pigs, whether it is your own pigs or supplying it to someone else’s pigs, is high-risk if the disease gets here. Any food waste needs to be heated to 100C for an hour to destroy disease-causing bacteria and viruses.

If a FMD case is suspected, MPI will immediately enforce restrictions to stop all movement on and off the property. Tests take only a matter of hours to determine whether the disease has breached the border or it is a false alarm.

“We don’t need to wait for results to lock down that farm to make sure there is no further spread.”

If it is a positive result, there will be a national halt to livestock movement as MPI traces movements to and from the infected farm. The length of time will depend on the spread of the disease.

One of the problems with the disease is that animals can shed the virus before they have clinical signs and it can take anywhere between three to 14 days for clinical signs to show up.

That reinforces the need to be prepared and have biosecurity measures in place on the farm – in case the worst-case scenario happens.

Make sure you:

purchase stock from reputable suppliers

purchase stock from reputable suppliers- keep a simple on-farm biosecurity plan handy and update it regularly

- consider vaccines for local diseases

- have easily identified farm animals (tagged or marked)

- minimise contact between your stock and other animals (for example, on neighbouring properties)

- record new stock entering the farm

- quarantine new stock away from existing stock until you’re sure they are healthy – at least for one week but preferably two

- check feed labels to make sure they are suitable for the stock

- manage the potential contamination of people, vehicles and equipment entering and moving throughout the farm. For example, ask visitors to clean their footwear before walking around the farm and as they leave

- follow routine best practice biosecurity measures such as disinfecting farm equipment and maintaining intact boundary fences where possible

- consider developing a detailed farm health plan with your vet.

Don’t:

- feed ruminant protein to ruminants (such as cattle, sheep, lambs, goats, deer, alpacas and llamas)

- feed pigs food that could contain (or have contacted) meat, unless it has been cooked for 1 hour at 100 degrees Celsius

- let overseas visitors near stock for a week after they were last near animals or infected places overseas

- let overseas visitors bring contaminated shoes or clothes onto your farm.