Forecasting global movements

The fertiliser supply chain has a complex array of supply and demand dynamics. Where are they at now and what could it mean for price?

Words Anne Lee

When it comes to factors affecting price, fertiliser has more than most farm inputs: war and unrest, major exporting countries’ government-imposed import and export regulations, shipping issues, global agricultural policies and exchange rate are all at play.

Some will mean increases in supply, some decreases, while other factors could also have an impact on demand.

The complex web of interactions means reading the market signals and forecasting pricing can be tough and unexpected volatility is still the watchword for the major fertiliser processors.

Ravensdown Chief Operating Officer Mike Whitty said in late February his sense of the market forces suggested prices remain similar on current levels unless China lifts its export ban on manufactured phosphate and urea and begins feeding supply back into the international market. Then there could be a slight weakening.

“If demand spikes in the Northern hemisphere as they go into their season – in particular in Brazil because of the sheer volume they pick up, we could see prices follow those demand spikes, but outside of that we would expect to see a situation where there’s likely to be more weakness than prices trending the other way.

“Now the big question that is still sitting there though, is what happens in the Middle East.”

China is a major producer of both nitrogen and phosphate products, but over their spring season the Government has imposed export restrictions so prices to their own domestic farmers would remain lower.

There was an expectation the ban would be lifted once they had gone through their main growing season, but it was likely it would be reapplied next season creating cyclical volatility in international prices.

India too is a significant agricultural country due to its size and farm production relies heavily on subsidised fertiliser. “They are trying to be more self-sufficient with fertiliser, but that’s not going to be the case for processed products such as diammonium phosphate (DAP),” Mike says.

“They go to tender on a regular basis for big volumes and that then pulls volume out of the market. Between China and India there’s a 30% variation on the free on board (FOB) price of urea depending on who is in the market, if the export ban is in place and how they’re tendering. That adds a lot of volatility and I’d expect that to continue.”

Last year saw an example of both countries’ influence with the Indian government cutting the fertiliser subsidy by 30% on processed phosphates such as DAP. That dropped demand from Indian farmers and saw prices come back slightly on previous price hikes. But the drop in supply from China’s export ban resulted in prices increasing 50% and has kept them at these levels.

At current prices of about NZ$1300/tonne they’re still well below the highs of 2022 when DAP was sitting at about NZ$1800/t. Likewise, urea had gone from NZ$1400/t (US$900/t FOB) to sitting just below NZ$900/t (US$400/t FOB).

The other big piece of the equation is the New Zealand dollar value relative to the United States currency. It has fallen about 5% over the last year and is 20% below values of three years ago. “A lower dollar is good from a farmer point of view in terms of export returns, but it’s not good for imported farm inputs.”

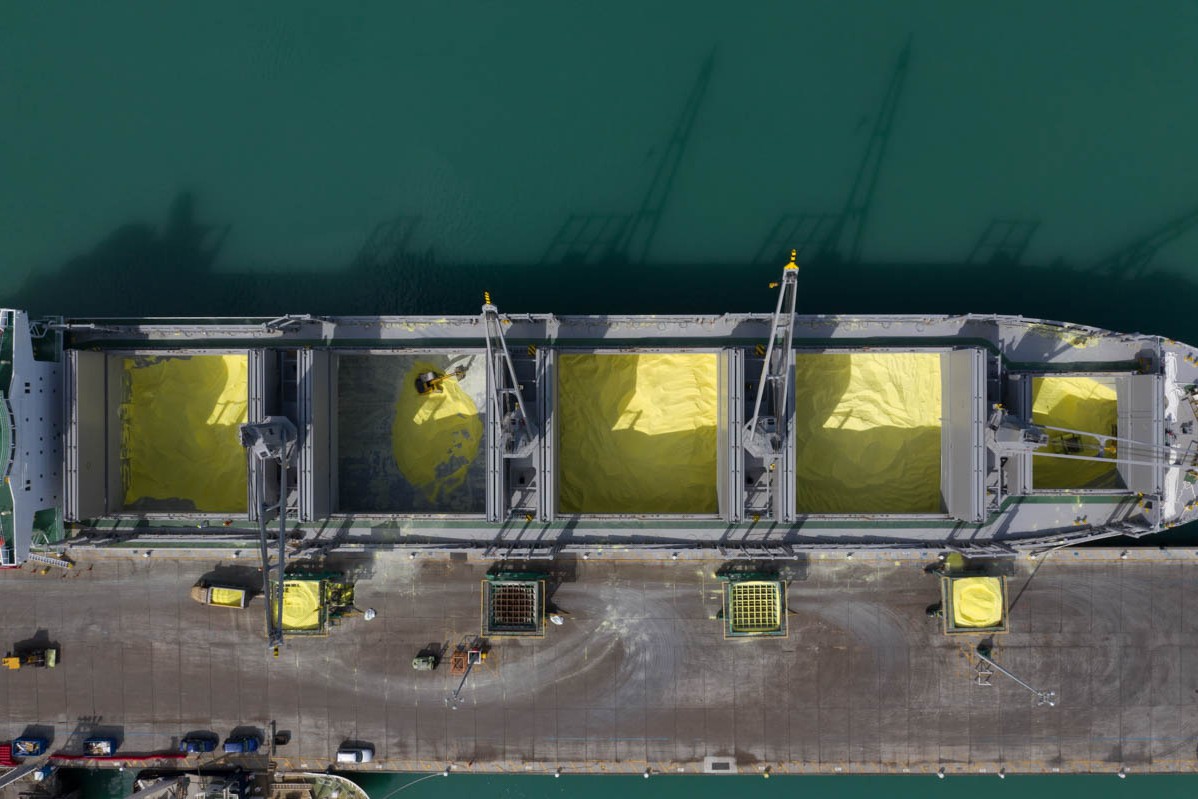

Mike says ideally the co-op would only buy at times when prices for products such as urea and processed phosphate were at cyclical lows, but it’s not possible to physically store all that product onshore and there is the risk of further depreciation where global dynamics change.

In terms of rock phosphate for superphosphate manufacture in New Zealand, a greater proportion of imports are now coming from Togo in West Africa rather than Morocco and Western Sahara which had been the focus of a long-running land dispute.

Ravensdown is also sourcing phosphate rock from Queensland, Australia and had used suppliers in China and Vietnam at times. The diversification away from Moroccan-sourced rock had helped reduce costs of the raw product.

Moroccan phosphate has always been touted as high quality, but the shift towards other sources hadn’t caused major increases in manufacturing expenses. The Australian rock from the Centrex-owned Ardmore mine is high quality and while that mine is still in a development phase, expectations that it will soon be producing about 600,000t/year building to 800,000t bode well for New Zealand in terms of a close-to-home supply source.

Mike says global shipping has not recovered to pre-Covid levels in terms of delivery times and capacity with ongoing conflicts still taking their toll. “Pre-Covid we were probably in the 90’s if you want to use a scale out of 100 – it was pretty much a given that product turned up when you expected it. But it’s sitting around the 50’s and 60’s now. It’s better than Covid times, but it’s certainly not back up to where it was.”

That means close management of supply chains, assessing and reassessing supply chain performance and factoring in lead times on delivery dates. “It’s why having multiple suppliers is important as well,” he says.

The Russian Ukraine war initially had a big impact on fertiliser supply out of Russia, but that country had pivoted successfully to supplying countries it is more aligned with so that its exports are likely to be back up to 100% of what they were pre-war.

That’s meant a re-jigging of who is sending what to who and has helped ease some of the supply constraints particularly around products such as potash and urea and to some extent phosphates.

The Israel Hamas conflict in Gaza is creating disruptions for some countries, but hasn’t had any major impacts for New Zealand fertiliser imports to date even with the disruptions in the Red Sea because NZ supplies largely come in bulk shipments which don’t use those routes.

“But like everyone we are watching that carefully. There are a lot of factors at play still in global supply and demand so yes, volatility is still a risk although, dare I say, it’s looking a little less so than we’ve seen in the past two years.”