Gains grow in the detail

Simple, repeatable systems are proving to be a winning formula for North Otago couple Peter and Emma Smit. They spoke at a recent Pasture Summit field days to find out just what those systems entail and how the Smits achieve top-performing financial returns. Words Anne Lee, Photos Holly Lee.

Peter Smit is a master of the understatement and as economical in highlighting his own successes as he is with his on-farm costs.

When the numbers do the talking for him though, there’s no denying that the high operating profit points to exceptional management and execution of the plan on the 313ha effective North Otago farm, Papakaio Dairies, owned by Peter and his wife Emma.

The couple were hosts of the South Island Pasture Summit event earlier this year, and a humble Peter shared some of the simple but very effective and efficient systems they use to achieve financial returns well ahead of the top 20% average for Canterbury.

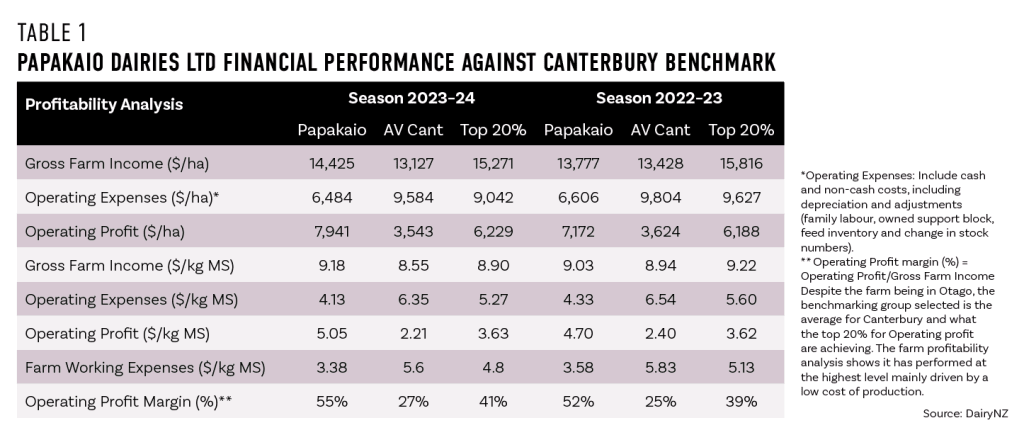

At $7,941/ha, their operating profit in the 2023–24 season was more than $1,500/ha higher than the average for the top 20% performers in the region on DairyBase. (See Table 1. Financial performance against Canterbury DairyBase benchmark.)

“Everyone is out there a lot – they’re out there getting cows out of the breaks, moving K-Line, etc. and they’re looking three or four paddocks ahead – they have a good understanding of what’s coming.” – Peter Smit, North Otago

But gross farm income was about $800 behind the same high-performing cohort, indicating Peter and Emma’s great results were driven by significantly lower costs.

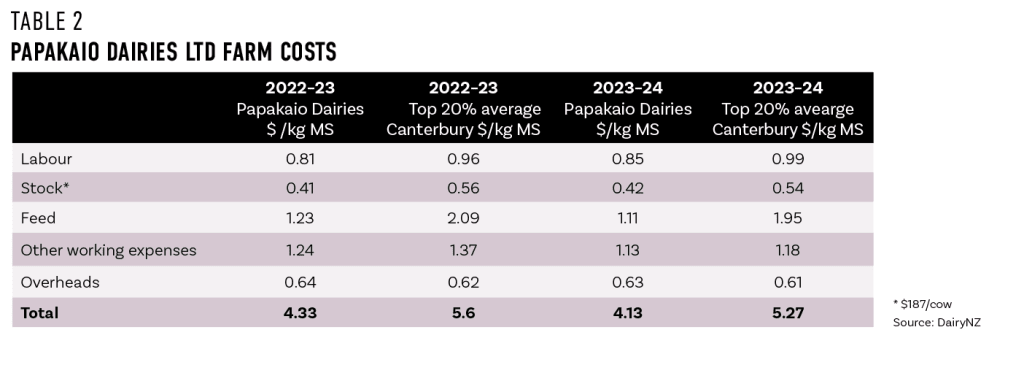

A detailed DairyNZ analysis put operating expenses at $4.13/kg milksolids (MS) and farm working expenses at an exceptionally low $3.38/kg MS. That’s $1.14/kg MS less than the average for the top 20%. Operating expenses take into account adjustments such as depreciation and wages of management, making it a more suitable metric for comparisons between farms.

A closer look at the costs shows that labour, stock and feed costs are where the biggest differences lie and that the gains come from simple plans on a well-laid-out farm where an experienced, long-standing farm team knows what has to be done and when, all while enjoying their work. (See Table 2. Farm costs.)

Farm manager Brad Cory has been with Peter and Emma for the past nine seasons, joining them when they were contract milking the farm, owned then by Peter’s parents Corrie and Donna Smit.

Corrie and Donna had bought the farm in 2015, while Peter was completing his Agricultural Science degree at Lincoln University, and employed a contract milker until Peter returned to the farm in the 2016–17 season. He too was employed as a contract milker and was joined by Emma the following season.

In 2021 the couple took ownership of Papakaio Dairies and now lease a 110ha dryland support block from Peter’s parents. They’re also in partnership with Peter’s parents and his brother Steven and his partner Tineke in a 320ha irrigated property, Otewai, where youngstock from each couple’s farms are reared and cows wintered. Each party pays a commercial rate on their use of the block and in total close to 3,000 cattle are wintered there.

Keeping it simple

Peter says over the past nine years there’s been significant redevelopment at Papakaio Dairies, with conversion of about 130ha under border dyke irrigation to pivots, the flattening of the borders and re-fencing

of the entire farm along with other upgrades to lanes and infrastructure.

It’s all been done with the aim of creating efficiency and enabling simple, low-cost systems.

Peter’s parents’ first season was the $3.90/kg MS milk price year and it’s that kind of challenge that sharpens the pencil, setting the scene for what has been a continued focus on low-cost systems. As Pasture Summit secretary and Darfield dairy farmer Al Rayne notes – simple systems are easier to manage and easier to manage well.

Over time, the Smits have made improvements to the pastures, the irrigation, the farm layout, the tracks, the fencing and the capability of the people, Al says. The simplicity of the system, coupled with the improvements, has brought about a honed operation.

And it’s the ability to get it right, doing those simple things really well every time with a “rinse and repeat” approach, that in turn brings profitable rewards, Al says.Pasture management is a prime example.

“We’ve re-fenced the farm so we have 100m-wide paddocks – that’s the luxury of having a square farm with no drains,” Peter says. “Every post is 12.5m apart. It makes it pretty simple.”

For instance, if cows have been allocated 24 posts for the grazing period but haven’t quite met the strictly monitored post-grazing residual of 1,500kg drymatter (DM)/ha, the next day they’re allocated 22 or 23 posts, Peter explains.

Everyone in the team can assess, monitor and adjust because they know what they’re aiming for.

Residuals drive pasture management decisions rather than any formal measurement of pasture covers or growth rates, but that’s not to say Peter and the team are ignoring those factors. Cows move paddock to paddock based on the next highest cover, with assessment of the total drymatter on offer done by eye.

Peter says everyone has plenty of experience now, thanks to low staff turnover, and allocation discussions based on residuals are part of the everyday focus on farm.

“Everyone is out there a lot – they’re out there getting cows out of the breaks, moving K-Line, etc. and they’re looking three or four paddocks ahead – they have a good understanding of what’s coming.

“We are a pasture first system and we’re definitely focused on high utilisation of high-quality pasture, but we also want to fully feed our cows so we use some supplement in the shoulders as needed,” he says.

Stocking rate

Stocking rate is key to achieving that goal of well-fed cows while keeping costs down. It’s comparatively low for Canterbury/North Otago, set at 3.2–3.3 cows/ha over the past seven seasons, down from 3.5 cows/ha from 2016–2018. Over the past two seasons cow numbers have been maintained close to 1,000 with bought-in feed totalling 450–600kg DM/cow/year.

They feed about 200t of PROLIQ or 1kg/cow/day through the milking season as well as about 200t of palm kernel in the spring and about 120t in autumn along with a small amount of silage.

Asked if he is tempted in a higher payout year to use supplements such as dried distillers grain (DDG) to pump up production and the income line, or if he ever considered pushing stocking rate so that it was harder to make mistakes with grazing management, Peter says the temptation can be there, but he knows it will just bring more work and complicate the operation. More cows mean more costs, he says.

“And there’s a big difference milking 1,000 cows versus milking 1,100 (through the 50-bail rotary platform). Those two extra rounds mean another 20 minutes of milking and that means cups on at 4.10am rather than 4.30am, and I know I’d rather be getting up closer to 4am than 3.30am.”

“I’d rather mate the yearlings and do one herd for five weeks than be up there picking cows from the whole (1,000-cow) herd.” – Peter Smit, North Otago

The incremental gains make a difference – 20 minutes a day, twice a day adds up over a year. Putting in an automatic vat wash has saved 10 minutes a day – another incremental gain.

Upgrading the effluent system so it is now spread via pivot instead of a travelling irrigator saves hours a week as well as helping with peace of mind and allowing better use of nutrients in the liquid green gold.

Peter says as paddocks have been renovated new pastures have been sown in diploids with medium- and large-leaf clovers included and sown to an optimum depth to get good establishment.

Paddocks are undersown in a tetraploid hybrid such as Mohaka if they’ve suffered from pugging or grass grub damage.

Winter and spring

Fodder beet is grown on 8ha of the milking platform with half of that used in late April and May to transition cows for wintering. The other half is used for 200 early calving cows, wintered on the platform.

Peter says the wintering block for 600 of their cows and 200 of his brother’s is dryland, so having crop on the irrigated platform gives “some wiggle room” with more consistent yields there. The wintering support block is sown in 25ha of fodder beet with about 75ha in grass which is cut for silage through the summer.

Cows are fed 9kg DM/cow/day fodder beet and about 4.5kg DM/cow/day of silage. Once they have finished the fodder beet, they move to grass, spending about two weeks there until they are moved back to the milking platform in small groups as they approach calving.

Cows are fed 9kg DM/cow/day fodder beet and about 4.5kg DM/cow/day of silage. Once they have finished the fodder beet, they move to grass, spending about two weeks there until they are moved back to the milking platform in small groups as they approach calving.

That makes early spring management on the dairy farm simpler and enables better pasture management and protection of soils. Peter and Emma’s remaining 200 cows are wintered on another property, also on fodder beet.

The spring rotation planner is used as a guide for the first grazing round in spring, although Peter says they are generally on a slightly faster round at the start, lengthening it to be closer to the spring rotation planner as they approach the end of the first round, about 18–22 September. Palm kernel is fed in troughs in the paddock to help meet demand in early spring. They start the second grazing round at about a 30-day rotation but speed up to 23 days towards the end of it and go into the third round, heading towards balance date at a 17–18-day round.

Peter says the aim is to maximise intakes, and pre-graze mowing has helped this, particularly as pasture grasses go into heading mode. Last spring was a good growing season and he pre-graze mowed the whole round from 28 October to keep quality and intakes up. He mowed another round going into summer and says from there it was just the odd paddock.

“We are going quite fast through that third round. We sacrifice yield for quality as we approach heading date. With a low stocking rate, we know a pasture surplus is not far away.”

Any re-grassing is done following balance date, with new grass back in the round prior to Christmas. The aim is not to make silage on the platform but it is used as a tool to manage surplus when required.

As they head into autumn, the round is slowed to about 30 days in April and 35 days in May. It had been 40 days through April and 50 in May, but Peter’s aim now is to go into winter with a lower cover and fewer long paddocks so cows aren’t having to eat low-quality, rank, yellowing grass in spring when their energy needs are highest. The fact cows are now coming home in small groups for calving means smaller areas are required early, giving pastures more time to get going.

Mating

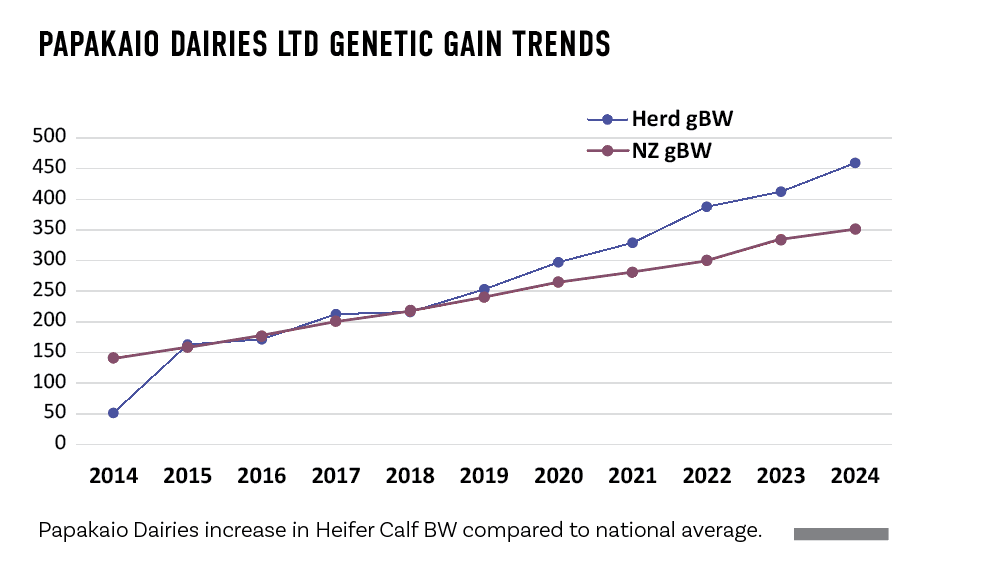

Over the last three seasons, Peter has been focusing on improving the genetic merit of the herd with the aim to improve efficiency of converting grass into milk and improving per cow production so that methane efficiency also improves. If a cow can turn more of that grass into milk on top of what it needs for maintenance than another cow, then she’s able to produce more milk per kg of methane emitted, he says.

Their emissions profile, based on Fonterra’s Farm Insights Report, is 9.5kg CO2e/kg MS compared with a benchmark of 10.3. Their methane emissions from cows and replacements make up 6kg CO2e/kg MS compared with the benchmark of 6.4.

The six-week in-calf rate has steadily improved and sits at 78% – well above the regional Canterbury average of 70.3% and 2% better than the top quartile.

Peter says cows are in good condition coming back from wintering and recover well from calving. An early calving herd is easier to get back in calf, and as the six-week in-calf rate begins to improve, it keeps getting easier. Incremental gains will keep building on themselves. The key to good results from mating is ensuring you’re mating cows that are actually on heat. “If in doubt, don’t put her up,” he says.

They don’t record pre-mating heats but do write the date the cow is mated on her back along with tail-painting her to identify returning cows.

Big genetic gain improvements have come from only using artificial insemination (AI) on the top Breeding Worth (BW) cows.

“We started out by putting the bottom BW cows to Hereford and then we increased that to the bottom 20% and then bottom 25%,” explains Peter. “Then we realised, if we mated our yearlings we could run a separate herd in the cows with the bull and not use a beef straw at all. So, for the last three seasons we’ve had a herd we don’t breed from and those cows run with a Jersey bull from day one of mating.”

That means Peter is having to pick from fewer cows each day for AI.

“I’d rather mate the yearlings and do one herd for five weeks than be up there picking cows from the whole (1,000-cow) herd.”

At calving, the springers mated to the bull are run in separate groups to those mated to AI to help with calf identification.

Yearlings are mated using a single prostaglandin (PG) injection with a 10-day mating period. This works well with using sexed semen as it maximises the number of sexed straws they can use.

“We have a set number of straws per day for our allocation and for us that’s seven straws a day, so in total we use 70 sexed straws for 230 yearlings.”

An LIC analysis shows that the overall mating policy resulted in 75% of the farm’s replacement heifer calves born in 2024 coming from the top 50% BW cows, and 41% were from the top 25% of BW cows.

Peter was disappointed that 7% of replacements came from the bottom quartile but says that’s probably because they haven’t selectively mated the yearlings and closer attention needs to be paid to calves coming from those heifers and whether they should be reared as replacements.

He uses Alpha-nominated semen from LIC – using one bull each day from a team he has selected including a mix of genomic and daughter-proven bulls. They’re mainly crossbred but he does select the occasional Friesian and Jersey straw to get a bit of hybrid vigour.

“I use the RAS list and order the animals from highest to lowest BW and then put in a few things like only show animals that are positive for fertility, udder overall score more than 0.5, and dairy conformation score more than 0.5; then I sort through the bulls it spits out – it’s not actually that many. I look through their lineage and their pedigree and if they have dams that have good maternal lines and good numbers of lactations, consistent lactations – I’m definitely more likely to pick those bulls.”

Peter says he’s happy to use some genomically selected bulls because he’s chasing genetic gain, and while it may give more variability, the bell curve has a higher upper quartile.

Peter herd tests four times a year because the data is important for his culling and selection criteria to lift genetic gain. The top quartile BW cows are producing 55kg MS/cow more over the season than the bottom quartile.

He’s also invested in scales so he can measure liveweights to inform the Production Worth and BW information.

“If we keep a focus on our costs, do a lot of the repairs and maintenance ourselves – like servicing our own pivots, servicing our own cup removers, teat sealing heifers – we can make all those small gains add up.

“Having simple, repeatable systems that our team really understands means they get very good at executing those systems.

“Then focusing on the breeding means we can make gains every year and they add up over time too. I think we’re just starting to see those come through in our cows now and we’re getting the results for better spring management. It does take time and you do have to be consistent, although there will always be some seasonal variability.

“But there’s no need to complicate things – the more complex, the harder it is to get right.”