Growing the beef pie

Advancing beef-on-dairy will create win–win opportunities for dairy and beef farmers to improve returns and make emissions savings for the pastoral sector. Words Anne Lee.

Focus on the bull not the breed when it comes to using beef genetics over your dairy herd, and be on the lookout for the ‘curve benders’. They’re the bulls that can produce beef-on-dairy cross calves with relatively low birthweights that go on to out-perform others in terms of carcase weight.

“They’re marketing the beef-on-dairy as an advantage in terms of its lower carbon footprint. There’s a real opportunity for New Zealand around that.” – Dr Jason Archer, Beef + Lamb New Zealand Head of Genetics

of Genetics Dr Jason Archer.

They were just two messages from a beef-on-dairy workshop at this year’s South Island Dairy Event (SIDE), held in Timaru earlier this year.

Beef + Lamb New Zealand (B+LNZ) Head of Genetics Dr Jason Archer says New Zealand sits in a unique position globally in that the relativity of our dairy and beef populations is the reverse of other nations.

“We’ve got a big dairy industry compared to a small beef industry, whereas if you look at Australia and the US particularly, they’ve got big beef industries and relatively smaller dairy industries. So, they have a lot less of a problem and with significant feedlot finishing, a lot easier system to fit their surplus dairy calves into,” he says.

“But an opportunity is just another way of flipping around a problem, right?”

Given that reasoning, the size of the opportunity for New Zealand is a big one, he says. He concedes that there’s just not enough suitable land in this country to rear every surplus dairy calf to finishing status, but there is room for a significant proportion.

Both the dairy and beef sectors have started on the journey but they are already playing catch-up with other countries.

Ireland has taken a zero bobby calf approach and have so far managed to reduce their numbers to 15,000/year out of a dairy cow population of about 1.6 million. Culling required due to TB regulations and other issues mean they are close to bottoming out at that number.

Jason says the impetus really grew in Ireland when the milk processing co-ops declared that all calves must be reared to eight weeks old.

If farmers want to sell the calf before eight weeks, they need to ensure there is a market for it and that’s driven the focus on using better beef bulls to produce calves the market wants.

Ireland exports about 200,000 calves to Europe each year and with them goes their greenhouse gas emissions. Any interruption to that market would mean the emissions remain in Ireland and the industry there is concerned that would incur penalties.

“They aren’t worried about being able to finish them – they know they have the capacity to do it, but it’s the emissions that would come with them that causes the concern,” Jason says.

Each beef animal’s greenhouse gas emission efficiency can be calculated at the point of slaughter. Every calf that goes to slaughter has a known birth date and the weight at slaughter is measured so a greenhouse gas emission efficiency value can be calculated, he says.

In the United Kingdom, supermarkets have already turned the beef on dairy product into a big win in terms of sustainability. They are actively marketing low carbon emission beef.

“And essentially when you dig into what’s behind that claim, it’s that they are doing beef on dairy,” explains Jason. “They’re marketing the beef on dairy as an advantage in terms of its lower carbon footprint. There’s a real opportunity for New Zealand around that.”

New Zealand’s pastoral industry has to take a partnership approach to build the beef on dairy sector and while the journey is under way, more education is needed and actions must come from farmers – both beef and dairy – and from the meat processing sector.

“They aren’t worried about being able to finish them – they know they have the capacity to do it, but it’s the emissions that would come with them that causes the concern.” – Jason Archer,

Beef + Lamb New Zealand, Head of Genetics

There has already been significant work done on identifying beef bulls to use over the dairy herd through the Dairy Beef Progeny Test programme, and efforts have ramped up over the last two years to raise awareness of it so that dairy farmers will use it for bull selection.

The Dairy Beef Progeny Test programme has been running for close to 10 years. In recent times it has been funded 50/50 by LIC and B+LNZ, but from the current cohort onwards it will be funded by B+LNZ. Dairy farmers contribute to the organisation through the levies they pay when animals go to the meat processor.

In the beginning, the Dairy Beef Progeny Test aimed to demonstrate that beef estimated breeding values (EBVs) do in fact predict performance of calves born from a dairy cow. Attention was on calving ease and weight gain. Once that was achieved, the focus then changed.

“It became more about identifying some good sires across multiple breeds that actually do the job and then hopefully getting some of those sires disseminated out and used in industry,” says Jason.

“And that has happened. This year we’re taking a slightly different approach and so we’ve got some different farms involved – Taranaki Dairy Trust, a farm in North Otago and a Massey University Farm – so we’ve got it spread across more regions, a bigger variety of cows.”

The vision for the programme is to test more bulls and have other companies also testing bulls using the same evaluation process so that information can be fed into a common platform.

Farmers can access the programme data to help make their selection for beef semen by going to the B+LNZ website, as well as looking for Dairy Beef Progeny Tested bulls in the bull catalogues put out by the breeding companies.

Progeny testing results show there can be significant variation between bulls within breeds and between breeds, so it’s the bull not the breed that matters, Jason says.

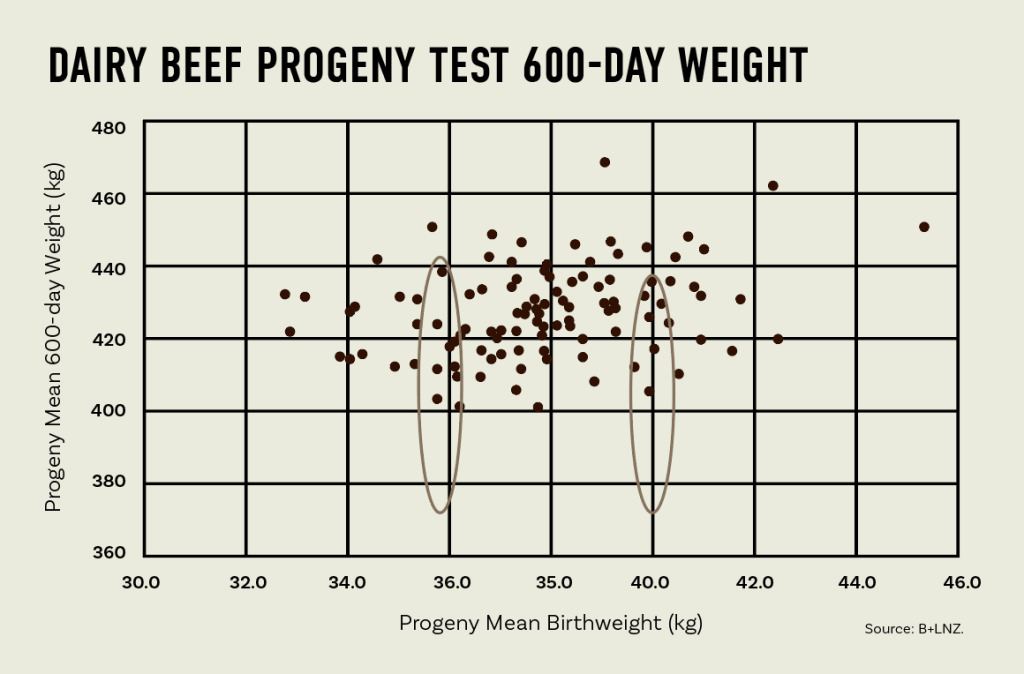

Data collected so far shows that for a given birthweight (BW) there can be a wide variation in 600-day weight which represents a typical age for slaughter.

If we look at the calves with a 36kg BW, we find there’s a range of about 50kg at that 600-day point.

“There’s a huge variation and a huge opportunity in selecting the right bull, because in that case it hasn’t meant any changes for you on farm – the calves are the same birthweight, but you’ve got some that are doing a lot better than others and will be more profitable right through the whole value chain.”

In real terms, that 600-day difference in carcase weight is worth about $175/head from the average animal at a $7/kg schedule average.

“We need to be collecting information right through the value chain over the life of those animals,” continues Jason. “Marbling is a good example of that because there’s a premium being paid for that.

“We need to be collecting information right through the value chain over the life of those animals,” continues Jason. “Marbling is a good example of that because there’s a premium being paid for that.

“Again, think about the bull not the breed because the data shows significant variation within breeds too. It’s pretty well understood that Angus tend to be different to Hereford and have higher marbling levels, but you can actually find some really good marbling Hereford bulls too.”

Equally you can find poor marbling Angus bulls.

If farmers are going to buy natural service pools, Jason strongly suggests buying recorded bulls.

“Every beef-on-dairy calf is sold an average of 2.8 times in its life, so at the point of sale we want people to be able to easily and simply identify the animals with the good beef genetics.” – Ben Watson. GENEZ

This year B+LNZ have launched the nProve website which enables farmers to select beef-on-dairy sires by inputting the emphasis they want on calving EBVs that include calving ease and gestation length, finishing EBVs that include weight gain and carcase EBVs.

Because of breed society differences, the selections happen within breeds rather than between breeds. Jason suggests focusing on a small number of EBVs.

“If you look at a typical report of bull EBVs, there are about 50-something pieces of information on that, but there are probably only about five or six from a beef on dairy perspective that you really need to be looking at.”

He also cautions dairy farmers to remember the information and acronyms in ‘beef language’, so BW means birthweight, not breeding worth.

GENEZ General Manager Ben Watson told attendees at SIDE that creating markets for surplus calves does require dairy farmers to be more proactive about beef bull selection, with more thought going into traits beyond gestation length and calving ease.

Rearers and finishers are looking for animals that will grow quickly, finish faster at good carcase weights and with good meat characteristics such as marbling.

GENEZ is a specialist beef-on-dairy genetics company targeted at dairy farmers and offers elite beef semen selected to meet the needs of dairy farmers, beef rearers and finishers.

He says the company was born out of his family’s dairy farming business’ knowledge and interest in genetics. He and his wife Stacey are equity partners in the Watson family’s three dairy farms in the Waikato and King Country, milking about 1,500 cows. Ben explains they stream the herds with the home, Stoney Creek herd, the top breeding worth (BW) herd in New Zealand a few years ago and third for production worth (PW). The operation has a high percentage of Jersey and crossbred genetics and he says they identified that created some risk to them in terms of non-replacement calves if there was a shift further away from bobby calves.

The family had already been focused on beef-on-dairy with his grandfather and father building a bull beef business as early as the 1970s, prior to conversion to dairying in 1987. When talking with dairy farmers, Ben says their top concerns are that beef bulls will cause calving problems and that they will spend money producing a beef calf but won’t be rewarded for that.

“We’ve literally got to the stage now with selecting beef bulls for use with dairy where there’s very reliable information on that – so if you select bulls with the data we have available now, you’re probably going to have fewer calving issues than you would with a straight Friesian bull.”

There are good bulls for use over dairy in every breed and bulls you would want to avoid, so the adage that it’s the bull not the breed is a critical one, he says.

Finding the curve benders when it comes to lower birthweights but exceptional growth rates and high carcase weights at 400 or 600 days is a good aim. About 70% of the beef animals slaughtered in New Zealand start their life on a dairy farm, says Ben.

“I think there’s an opportunity if we gear up on the genetics – so our surplus dairy calves have the right characteristics – that we could rear 500,000 to 1 million animals to slaughter, preferably in that eight-to-20-month timeframe.

“This eight-month early slaughter manufacturing beef system has a carbon footprint unmatched anywhere in the world, but would need to be rewarded per kilogram as the first four months of life are the most expensive and the lower carcase weight gives fewer kilograms to dilute that.

“This kind of system is going to give the pastoral sector some obvious advantages around wintering and around emissions reductions. Every beef-on-dairy calf is sold an average of 2.8 times in its life, so at the

point of sale we want people to be able to easily and simply identify the animals with the good beef genetics, and that’s why we sell a tag that’s linked with the EID tag and can be with the animal for

its lifetime.”

In the future, meat on a supermarket shelf or tissue from calves born from semen the company supplies could be genomically tested. The traceable capability allows data to be collected throughout the animals’ lifetime and creates a marketable story and point of difference that rearers, finishers and processing companies can use.