Hunting down poor repro reasons

Is pasture enough when it comes to managing energy deficits of high-performing cows? Anne Lee reports.

A mating benchmarking project that used data from cow collars, blood tests and pasture quality information has highlighted to the team at Lincoln University Dairy Farm (LUDF) that there may be some shortcomings with their pure pasture system when it comes to transition and mating.

A mating benchmarking project that used data from cow collars, blood tests and pasture quality information has highlighted to the team at Lincoln University Dairy Farm (LUDF) that there may be some shortcomings with their pure pasture system when it comes to transition and mating.

Traditionally 100% pasture for early spring, transition feeding for cows after calving will this year include baleage in an effort to improve early rumination.

During the mating period, especially through weeks four to six, the benchmarking project raises the question: is pasture enough when it comes to managing energy deficits of high-performing cows?

The farm’s consultant Jeremy Savage from MRB concedes that while the benchmarking project has collected a lot of data it hasn’t been a study set up with scientific protocols.

“More science needs to be done before we’d be confident in making any change to diets and bringing in supplements on the basis of improving reproductive performance,” Jeremy says.

But there’s enough data to warrant further investigation and analysis of options for adjusting the feeding regime and it’s certainly been worth asking the question, he says.

The reproduction benchmarking project carried out at LUDF over the past year has used data from Allflex cow collars coupled with blood test information, pasture quality samples and pregnancy scanning to take a close look at what’s happening within the herd.

A detailed comparison has been made with Alderbrook farm – a 659-cow, 200-hectare farm share-milked by Liam and Lauren Kelly and owned by Marv and Jane Pangborn.

Cows were wintered at Alderbrook in the study season.

Liam and Lauren have consistently been able to achieve empty rates of 7-10% from 10 weeks mating while the otherwise high-performing LUDF has been plagued by empty rates of 16-20%.

The Kellys feed a mix of grain, palm kernel and proliq through the spring period.

Both LUDF and Alderbrook use Allflex collars – last season was the first for LUDF while Liam and Lauren invested in the collar technology three seasons ago.

The collar information has allowed detailed analysis of rumination and activity data along with cycling rates both pre-mating and during the extended 12.3-week mating period in 2022 on both farms.

Each farm used the heat detection alerts to determine which cows were put up for mating.

Jeremy says the data collected has given the project team, including Waimate veterinarian Ryan Luckman, insights into where the problems LUDF has been experiencing with high empty rates are occurring and what the reasons could be.

Analysis over the years has suggested LUDF’s problems may have been in holding early pregnancies and conception rate drops after the first cycle of artificial insemination (AI).

Conception rate comparisons show that Alderbrook’s conception rates remained about 60% after the first round of mating, from week three, and there was generally little difference between conception rates of first and second lactation cows.

LUDF’s conception rates, on the other hand, dropped away in weeks four and five to between 39-45%, rising again briefly in week six to 60% before falling away again.

NEFA showing energy deficit

Blood tests have provided another clue into what’s going on.

They were taken from calving through until Christmas with a focus on non-esterified fatty acid (NEFA) levels. High NEFA levels in blood show an animal has been mobilising body fat and is an indication it has been in an energy deficit – so the energy it’s getting from feed intake is less than the energy expended in maintenance, activity and producing milk.

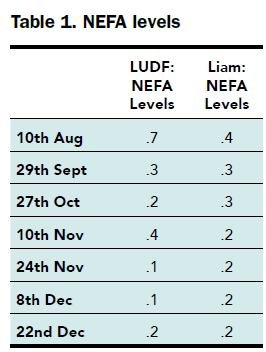

Table one shows LUDF’s NEFA levels were higher immediately post calving, while Alderbrook’s levels were significantly lower.

LUDF’s levels dropped but rose again in November at the same time as conception rates dropped off.

That rise shows an energy pinch and it’s something the farm team has noted in previous seasons at the same time in each season, Jeremy says.

That rise shows an energy pinch and it’s something the farm team has noted in previous seasons at the same time in each season, Jeremy says.

It’s also commonly observed on farms feeding only pasture at that time as seed heads in grasses start to emerge, he says.

Pasture analysis shows that while LUDF farm manager Peter Hancox and the farm team are able to maintain high pasture quality, holding it above 12 megajoules of metabolisable energy (MJME)/kg drymatter (DM) over that time, neutral detergent fibre (NDF) levels rise.

That corresponds with an increase in rumination levels above 500 minutes per day and the likely outcome is a drop in voluntary intake with maximum intake linked to NDF% of the diet, Jeremy says.

Ryan’s analysis of the rumination data on both farms and from an extended data set of Vet111 clients shows LUDF sitting in the lower quartile from calving to early lactation and positioned mid-way during the springer period.

Target rumination is 500 minutes per day. Alderbrook is among the top 2% of performers in Ryan’s data group when it comes to rumination and is consistently significantly higher than LUDF. All cows will drop rumination rates on the day they calve and immediately post calving as they recover.

The aim is to see them return to increasing energy intakes as indicated by rising rumination rates so they get to a positive energy balance as soon as possible.

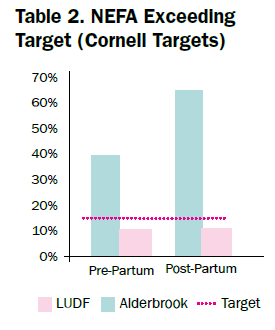

The NEFA blood test results grouped into pre and post calving show 40% of LUDF cows had NEFA levels over the target pre-calving and 65% of the herd was over the target post-calving indicating a large proportion of cows are in an energy deficit.

Alderbrook stayed within the target for both periods. Table two shows the difference in diets between LUDF and Alderbrook. Over the November pinch period Liam feeds:

Alderbrook stayed within the target for both periods. Table two shows the difference in diets between LUDF and Alderbrook. Over the November pinch period Liam feeds:

Grain 0.2kg DM

Palm kernel 1.5kg DM

Proliq 0.4kg DM

Total 2.1kg DM

If LUDF used a high-energy supplement over the same period, when growth rates are increasing and pasture supply is already likely to be ahead of demand, pasture substitution would occur.

That would mean wasted grass or require additional supplement to be made.

Balancing cost versus substitution

Jeremy estimates the cost of supplement to be $35/cow for the period if an equal mix of grain, palm kernel and dried distillers grain (DDG) was used. That’s a total cost of $18,935. If the net cost to replace a not-in-calf cow with a cull value of $700 is $1300/cow, recovering the $18,935 feed cost would require the herd’s empty rate to improve by 2.6%.

The cost of intervention – scanning and treating phantom cows with progesterone (PG) – totalled $2487.

700 cows scanned @ $3/scan

43 cows PG @ $9/treatment

While the phantom cow treatment would seem more cost-effective if collars are already being worn by cows than bringing in additional feed, Jeremy says more analysis on other effects of additional feeding would have to be done before any definitive advice. Likewise, the addition of bought-in, concentrated feed over the period would be a departure from a grass-only system and is likely to incur other costs associated with changing the system.

“There may be other ways to achieve an improvement in quality such as the timing of nitrogen applications,” Jeremy says.

What’s apparent though is more data and information, when analysed with a systems lens, can provide clues to where actions could be focused.

Key points for LUDF’s big drop in empty rate

LUDF empty rate dropped from 20% to 12% in 2022 mating.

- Mating period 12.3 weeks, an increase from 10 weeks.

- Ultra short gestation bulls used for the last two weeks.

- Collars used to identify cows for mating.

- Collars used to identify premating heats, heat activity and inactivity.

- Inactive cows scanned after the first round of mating.

- PG administered to inactive cows identified as empty, AI three days later.

- A 3.3% improvement in not-in-calf (NIC) rate attributed to longer mating period.

- A 5.4% improvement in NIC rate attributed to interventions using collar information.