Irish farmers face N limits

Ireland has strengthened nitrogen rules. Anne Lee explains them and how the system works.

IRISH DAIRY FARMERS HAVE been urged strongly to get on board with new nitrogen (N) regulations as the country strives to improve water quality or face even tighter limits from the European Commission.

The new rules are included in what is now the fifth update of the Nitrate Action Programme for Ireland.

Included in the wide range of actions, aimed at lowering nitrate and phosphorus in water bodies across the country, are updated values for the amount of N each cow is deemed to excrete.

That’s important because there are strict limits on the amount of organic N (largely from cow urine) allowable for each farm.

The total organic N limit is set at 170kg N/ha.

However, close to 7000 Irish dairy farms or just over 40% operate under derogation rules that allow them to have organic nitrogen rates of up 250kg N/ha, providing they adhere to a number of conditions.

one of the forms of Low-emission slurry

spreader (LESS).

Previously, each cow’s excretion rate was set at 89kg N/cow allowing a stocking rate of 1.91 cows/ha if not under derogation and up to 2.8 cows/ ha if the farm has derogation status.

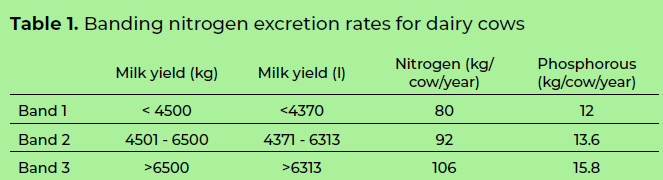

But Irish research has shown nitrogen excretion rises with milk yield and in the latest Nitrate Action Programme, a new system has been introduced where herds are assigned to one of three yield bands. (see table one.)

Lower-yielding herds – below production levels of 4370 litres/cow/ year – have been assigned 80kg N/ cow/year.

About two thirds of the country’s herds are estimated to sit in band two, and for them the nitrogen excretion rate has been lifted to 92kg N/cow.

At a farm limit of 170kg N/ha/year that would require a drop in stocking rate from 1.91 cows/ha to 1.84 cows/ ha.

Higher yielding herds – producing more than 6313litres/cow/year – have been hit even harder with a new nitrogen excretion rate of 106kg N/ cow/year.

It means higher-yielding cows operating outside of derogation with the 170 kg N/ha/year limit must drop their stocking rate to 1.6 cows/ha.

Farmers determine which band they’re in based on the average of their previous three years’ production or they can elect to use their previous year’s production alone.

The production data comes from their milk processor. That’s then aligned with their official recorded cow numbers to give their per-head yields.

If farmers don’t engage in the scheme they will be assigned to the highest-yielding band by default.

Derogation farmers, too, will face stocking rate reductions but for them the big risk comes if declining water quality trends aren’t reversing.

The EC has declared that where there’s risk of nitrate pollution or water quality is continuing to decline then derogation organic N limits in those areas will fall from a maximum of 250 kg N/ha to 220 kg N/ha.

Stocking rate on a mid-band farm operating at 2.7 cows/ha would have to fall to 2.4 cows/ha to meet that limit. The restrictions could significantly impact farmer earnings with material drops in milk income.

In a recent Teagasc (Irish equivalent of DairyNZ) webinar Department of Agriculture, Food and Marine (DAFM) nitrates and biodiversity inspector Ted Massey explained there were only three other areas with derogations from the European Commission.

They are the Netherlands, the Flanders area of Belgium and Denmark. All other member states had given up on seeking derogation or had been refused, he said.

The Dutch derogation clearly sets out a trajectory for transitioning out of derogation by 2025.

In March last year the Irish secured an extension to 2025 but based on water quality trends and the increase in cow numbers the commission has required Irish regulators to undertake water quality reviews every two years.

This year the data from 2021 and 2022 will be reviewed and where there’s a worsening trend or waters are deemed polluted the maximum organic N load will drop to 220 kg N/ ha from 2024.

Ted told webinar viewers there is a risk that a significant area or all of the country could move to 220 kg N/ha.

It’s critical all farmers work together to help stabilise and reverse the trends in water quality if there’s to be a chance of securing an extension of derogation in 2025, he said.

Data from 2021 showed that compared with 2017 annual chemical fertiliser use has risen 30-40 tonnes.

The national herd has increased by 12% and has become increasingly concentrated in the south east of the country.

While the latest 2022 water quality data had not been released at the time of the webinar earlier this year, the 2021 data showed close to half of Ireland’s rivers had unsatisfactory nitrate levels and two in five were showing an increasing trend.

Almost 30% of rivers had unsatisfactory levels of phosphate (P) with a quarter showing an increasing trend. Almost half of the country’s rivers were deemed to have less than “good” ecological status.

While the numbers are sobering and don’t bode well for the continuation of derogation and higher stocking rates, experts are still optimistic that if other sectors do their part and all farmers engage and adhere to the requirements of the Nitrate Action Programme, water quality can be improved.

Other changes to slurry

Most Irish farmers still house their cows for some proportion of the year resulting in significant volumes of effluent collection.

It’s typically scraped from the housed areas and yards rather than

washed down to help reduce the volume collected.

The resulting slurry is stored in large ponds or lagoons and is spread on paddocks as weather permits.

There are strict rules on the volume of storage required and the calendar period when it can be spread.

Ireland is split into soil management zones with Zone A’s slurry spreading period opening on January 12 followed by Zone B later in January and Zone C not beginning until February. Under the new Nitrate Action Programme the closed period has been extended with the closing date now October 1 – two weeks earlier than the previous data of October 15.

As with the nitrate derogation there are exceptions but this requires farmers being able to prove their land is suitable for spreading slurry up to October 15. Ministerial approval is required – so that bar is high.

The closed period for spreading of chemical fertiliser has also been extended in each zone.

Changes have been made to the rules around how slurry is spread in an effort to limit the potential loss of nitrogen and nutrients.

All farmers with grassland stocking rates of 150kg N/ha or greater must use low-emission slurry spreading (LESS) equipment this year.

Derogation farmers have already been working under this requirement.

Next year the rule applies to all farmers above 120kg N/ha and from 2025 the stocking rate trigger drops to any farmers above 100kg N/ha.

LESS equipment deposits the slurry at ground level through equipment such as a travelling shoe, travelling hose or shallow injection.

In the past tankers have been used with splash plates that spread the slurry widely from the back of the tanker. The LESS methods reduce nitrous oxide emission losses and leave less slurry on top of the pasture enabling more efficient use of the nutrients in the slurry.

Soiled water

The Irish call the wash down water, which contains effluent from the farm dairy and yard, soiled water.

Rules relating to the storage and spreading of soiled water have been strengthened too.

Farmers can no longer spread soiled water from December 10 to the end of December and from next year this extends to the full four weeks of December.

In 2025 the same rule will also come into force for winter milking farmers.

The requirements will add further capital cost to farmers with additional storage required.

This year they will need to have three weeks of storage for soiled water and from next year that will be extended to four weeks of storage.