He’s gained national and international industry awards and Jack Raharuhi sees his career as all about working with people. By Anne Hardie.

Jack Raharuhi has no desire to buy a farm and milk a couple of hundred cows with no staff. He would be lost without people and his career in the dairy industry is all about people management.

Jack Raharuhi has no desire to buy a farm and milk a couple of hundred cows with no staff. He would be lost without people and his career in the dairy industry is all about people management.

At 30, he has spent half his life working on corporate dairy farms and has charged up the ranks to the role of business manager at Pamu Farms of New Zealand’s $65 million Cape Foulwind farming operation. That encompasses three dairy farms milking more than 3000 cows, two support blocks, a machinery business and an 1800-hectare livestock block that is moving from deer to dairy support in a bid to reduce winter cropping and create a bobby-free business.

He oversees 24 full-time staff and four on fixed terms, from school leavers joining as farm assistants to farm managers in charge of large herds and he has learned a thing or two about people. He admits he is a “real over-communicator” who enjoys people.

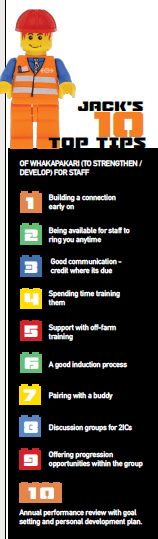

It has probably helped him over the years with his success in the Ahuwhenua Young Maori farmer of the Year, Dairy Industry Awards and then Zanda McDonald Award where he rubbed shoulders with leaders in the industry and has “taken all the gold nuggets” from them to add to his knowledge. About 90% of his role now is managing people and he says it is all about communication and keeping staff excited about their role in the business and where they are heading. He talks to the entire team and not just farm managers about KPIs, greenhouse gas emissions and the long-term goals of the business.

It is usually informal conversations as they drive around the farm and it is all part of making staff feel a connection to the business and being interested in the role they play. At the same time, he asks about families and life outside of the farm to create bonds that help staff feel connected.

“It’s building that connection early on and saying they can ring any time. Someone won’t ring you if you haven’t got that connection early on.”

Staff go the extra mile if they feel they are supported and their leadership shows empathy, though Jack warns there needs to be a balance between being an empathic leader and professionalism. Otherwise, some individuals will take advantage of an empathetic leader, he says. Finding that balance depends on the individual personalities of staff members, he says.

The industry is changing and Jack says communication is becoming more important than ever to attract staff, retain them and keep them interested. In particular, staff under about 23-years-old are needier than they were 10 years ago and seek more communication.

“They love to be acknowledged and praised and they love to feel a part of something. They love to chat about things in their personal lives. Staff are bringing a lot more to work than they used to.

“I think they’re getting a lot softer. They want to be paid more to work less and lack a career drive. It’s just a job.”

He finds staff older than 30 tend to have grown up with a focus on career, mortgage and family. But when it is just a job and the labour market offers plenty of good-paying jobs, it’s easy to move on pretty quickly.

“You need a bit of stability and a bit of longevity in the business and the generation coming through doesn’t want to settle,” he says.

“The dairy industry is screaming out for staff so dairy farming is a good way to hop around if you are a young guy. You can get a job on the phone with a house and good salary and do it for six months and then head somewhere else.”

It takes time training people, so Jack says employers have to cater to what prospective employees want to make them want to stay. That includes making them feel part of something special.

“It’s not just financially. It’s stability, a good home, good working conditions and working facilities. It comes back to lots of little things, like firewood, Christmas functions and presents for the kids and putting on a lunch for all the staff every couple of months.”

The Cape Foulwind farms have 24 homes for staff – which means 24 tenancy agreements – that are part of employment agreements on top of salaries. Jack says labour shortage and rising inflation has lifted wages considerably. In the past, the corporate paid a base salary plus a bonus, but he says it was a hard sales pitch trying to describe what that bonus would look like when it was connected to aspects such as production and mating performance. Now, farm assistants get paid between $55,000 and $63,000 a year, plus a house if they want it. The 2ICs are paid about $75,000 plus a house and farm managers between $85,000 and $105,000 depending on herd size and experience, plus a house.

“There was a lot of debate about the bonus and a lot of people said they just wanted to get paid a figure, so we scrapped the bonus scheme this year and now their pay is highly competitive against the rest of the industry and no bonus scheme.”

Jack says attracting and retaining staff is critical for the business, which is why it employs a cook through the hectic August and September period to cook a hot meal for all the teams to eat at the end of the morning milkings.

Rosters have changed in the past few years and Jack says there will have to be more changes in future to attract and retain staff. Through the year, rosters on the Cape Foulwind dairy farms vary between four days on and two off, five days on and two off, plus six days on and three off.

The herds are milked twice a day through the season and each farm splits the herds so there can be three herds being brought in for milking in the morning and afternoon. For staff, that can mean a 3.30am start to get the cows in and a long day through to about 5.30pm, with two to three hours off in the middle of the day.

Big days, Jack says, but decent days off and a lot better than when he started in the dairy industry at 12 days on and two days off. It used to add up to 160 to 170 hours a fortnight and, he says, that is just not acceptable now.

“It was normal back then and you just had to crack on. When you are young, you have a bit more energy. But you get to your days off and you’re buggered. When you’re young you have a social life too and you can get quite fatigued.”

That becomes a health and safety issue onfarm and brings inefficiencies due to tired staff and they have learnt to work smarter and become more efficient.

“The workforce is changing really fast. We are going to struggle to find people who will get up at three in the morning – unless it is an old-schooler.”

Technology continues to improve and robotics is an option for the future. Flexible milking times is another option and Pamu has been using 3in2 and 10in7 on Canterbury farms. Jack says once-a-day milking in larger herds could lead to a 30% drop in production, so he is not keen on reducing milkings to that level.

Another option is splitting the team into shifts, with a morning shift on the early milking and an afternoon shift taking over for the later milking. All options will have to be considered to attract staff and retain them.

Part of the team

A buddy system helps new farm assistants find their feet when they join the team at Pamu’s Cape Foulwind dairy farms and Jack Raharuhi says the most important thing you can give them is time. For the first three to four weeks of their employment, new farm assistants with no dairying experience will stick with their buddy to learn the basics around the farm and gain some confidence.

“Someone coming in with no experience needs to enjoy the fundamentals first. They need the basics like meeting and fitting in with the team, riding the motorbike and learning to be punctual.

“In terms of teaching them, it depends on their personality and you pair them with someone who suits. We’ll put a young fella with the wise old bugger of the farm. And if you can’t pair them with anyone who suits, then you’ve hired the wrong person because they don’t fit with the team.”

After a few weeks with their buddy, the new farm assistant will be given minor tasks to carry out unsupervised and Jack says management will slowly loosen the leash over time as the new assistant gains confidence.

The induction process sets the scene for the employee in terms of what is expected in their role on the farm, including health and safety with the high-vis, personal locator beacon and radio whenever they are out on the farm. Importantly, they learn they are working as part of a team.

“We want people to enjoy work and who they work with. But we are also a high-performing business and we do expect tasks and quality of work to be to the best of their ability. We don’t want to scare them off on their first day, though.”

Occasionally, there is a manager who loves power and Jack says you have to manage that with new staff. Much of it is about personalities, understanding people and communication.

Employees are encouraged to work through the Primary ITO New Zealand Apprenticeship in Agriculture for dairy farming and Jack says they wrap a lot of support around the trainees to help them achieve their qualifications. Employees new to the industry get one-on-one assistance with information for the course to help them on their way.

In the past, Jack has held monthly apprentice workshops which was useful for getting all the apprentices together and taking them through the performances of the Cape Foulwind farms, then relating it back to their course. Now that he has moved up to the role of business manager, he no longer has the time to run the workshops, though he still tries to take the time to talk with the apprentices about their studies to maintain relationships.

He also ran discussion groups for 2ICs in the past to help them prepare for farm management roles because, he says, they too often go into farm management roles unprepared. It was also a good way of working out the potential of individuals. Discussion groups may start up again in the future, though next time he would select a few 2ICs who are focused on their next move. In the meantime, he works with individuals to make sure they know what is happening within the farm business and why, as they prepare for farm manager responsibilities.

“The 2ICs get dropped in the deep end as farm managers and you have to make sure they have all the support so they float. We wrap a lot of support around them.”

One of the advantages of a corporate operation is the opportunity to move employees into new roles on other farms when they are ready. Jack says there comes a time when 2ICs want to move up into a farm manager’s role and if they cannot do that within the business, they will leave.

“If you have a really good 2IC working with a farm manager, they’ll start to butt heads. They’ll try to suggest something better than what the farm manager is saying and the farm manager will refuse to do it because they don’t want it to be the 2IC’s idea.”

The alternative is to try and stimulate the 2IC by giving them more responsibilities, so you don’t lose them. Jack says losing a good staff member such as a good 2IC is like losing your investment.

He has lost good 2ICs that he has coached and mentored over the years who have sought job opportunities elsewhere, but sometimes they come back when a farm manager’s role becomes available. It comes back to communication, relationships and trying to be an employer of choice, he says.

On corporate dairy farms where a team works together over time, Jack says it usually causes disruption when a new farm manager is brought in from outside, rather than moving a 2IC up from the team. Part of that is due to the role of 2IC.

“The 2IC role is quite interesting. They’re the sounding board for all the farm assistants. The team is onside. If you’re willing to bring a new farm manager in, you will typically see a high turnover of the team.”

Sometimes that has to happen to bring fresh ideas on to the farm, especially if performance has been struggling.

“If you aren’t promoting internally, it usually means you want to change things.”

At farm manager level, those who can operate independently make Jack’s job easier. But, he says, it is important to maintain a good relationship with them.

“One thing I’ve learnt is to never assume anything and also keep a finger on the pulse because at some point things won’t go to plan. They have to stay responsible and you don’t want them to take advantage of you.

“Farm managers need to live and breathe it. If they aren’t engaged, they need to look for another job.”

Every year, each employee has a performance review which includes their personal development plan as well as goal setting. Jack says it is not just about their job, because other factors influence their work.

“An older dude may say he wants to build a shed on his block and a dairy assistant wants to be a manager. It’s personal and career goals – their career helps them with their personal goals.”

For Jack, his career path has been within corporate dairy farming and the people management of larger operations. It is a career with multiple opportunities in an industry that is constantly changing and he finds that exciting, albeit challenging.

“There’s some days you want to walk off the place because things go wrong and then you get days when the sun is shining, the vat is full and everyone is smiling.”