Long-time dairy farmer and Dairy NZ Climate Change Ambassador George Moss believes it is up to the individual and the choices made as farmers as to how GreenHouse Gas reduction targets are met. By Claire Ashton.

George Moss is wearing the standard black attire of any New Zealand farmer; black jandals, black shorts, and a black tee shirt when we meet on an early autumn afternoon at one of the two Tokoroa dairy operations farmed in partnership with his wife Sharon on Old Taupo Road.

George Moss is wearing the standard black attire of any New Zealand farmer; black jandals, black shorts, and a black tee shirt when we meet on an early autumn afternoon at one of the two Tokoroa dairy operations farmed in partnership with his wife Sharon on Old Taupo Road.

The black tee shirt was given to him by Dairy NZ as George is a ‘Dairy NZ Climate Change Ambassador’ and what differentiates him from perhaps the average or even high-performing farmer is his willingness to look at climate change mitigation, both personally and professionally, a journey he feels he has committed to for the past five years. Climate change is real for George onfarm and he fully believes humans impact and accelerate climate change. He has real concern for humanity’s future on the planet.

‘“An individual’s and a nation’s carbon footprint is strongly correlated to their wealth, both as a nation and as farmers we are privileged, and as such we have a responsibility to do our share. However it seems, all agree that something needs to be done, but we all think the other guy should do it”.

“The reality is that reducing a carbon footprint usually requires decisions that can impact on lifestyles and incomes.”

Some may take umbrage with equating wealth with responsibility, and George is aware that when he comments on the fiscal nature of the climate equation, it can ruffle feathers.

“The whole GreenHouse Gas footprint as related back to the individual and their choices is quite complex. While we can solve other issues such as nitrogen and phosphorus at a catchment scale (although not easily), the GHG problem is far more complex in that NZ Inc makes up 0.17% of the global footprint and as individuals our contributions are miniscule.”

“But that does not diminish our collective responsibility to the next generations – hence the benefits of doing the right thing are not measurable or transparent.”

George feels He Wake Eke Noa (HWEN) is a far more nuanced system than the ETS, and hopes it will be effective at maximising NZ Inc’s opportunities of various gas pools.

“Being a collaborative effort between primary industries, iwi groups and government, there are trade-offs and perfection is hard to achieve but it will create a mechanism that will see GHGs reduced to the best effect. But the government, if not convinced, has the power to still decline HWEN and put agriculture into the ETS.”

“A good way to look at these emissions is to consider them as part of a pool; we have a pool of methane, we have a pool of nitrous oxide and we have a pool of carbon and on a national basis we must make reductions across all of them and use the remaining to best effect,” he says.

Methane is a very potent short-lived gas, and despite its shorter longevity, it has a significant impact, and as such it is treated differently to nitrous oxide and carbon – a significant win for ruminant farmers.

A good analogy George uses is that if you think of a kitchen with an old Aga and you also have a gas cooker, and you’re cooking away, and someone comes in and says, ‘woah this is way too hot,’ the quickest way to reduce that temperature is to turn the gas cooker off or down.

Even if you stop putting the coal or wood into the Aga, it is going to carry on for a long time and the only way to drop the temperature is to put cold pots of water on it. So think of the Aga as carbon and nitrous oxide, your gas cooker as methane.

Onfarm George has measured methane on Overseer for the 20/21 year as producing around 68% of their total GHG footprint, nitrous oxide 21% and CO2 10%.

“Methane is the achilles heel of ruminant farmers globally and current potential mitigations will be hard to implement in our pastoral context.”

New Zealand farmers need to reduce methane by 10% by 2030, and George thinks it would be preferable to chip away at that percentage, using the time available to best effect, rather than wait until the last few years to tackle it. As for the 24-46% reduction of methane by 2050 George says all Kiwi farmers are hoping some innovative science comes around to help maintain production.

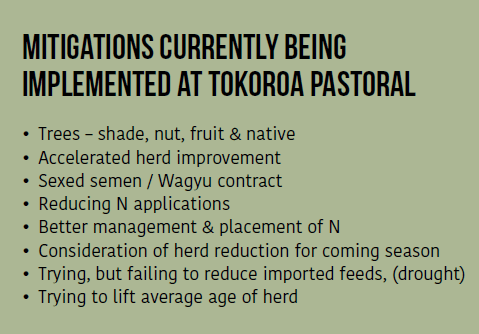

Modelling reduction mitigations

Five GHG mitigation options have been modelled on George’s Tokoroa Pasture farm on Overseer. These included removing all imported supplements from the farm system, reducing N fertiliser and removing imported supplements, rearing fewer replacements and planting sidelings in pine trees. Results are shown in Table 1. The only model that reduced GHG emissions and remained profitable was to rear fewer replacements.

Currently the farm rears 32% replacements of which 22% enter the herd and 10% are sold. This scenario is based on 15% heifers reared and both reduced N loss and emissions and increased profitability.

To make the heifer model work George says he has to lift reproductive performance by getting more heifers in calf, have less wastage in the form of empties and a tighter calving spread.

Where he would like to be operating is at a high production level with a short lactation window, ending up with a herd very efficient at converting grass to milksolids.

Certain breeding programmes and farmer preferences have focused on a variety of breeding traits which in the long term have led farmers away from that top performing cow who is an efficient convertor, he says.

“We need to implement a longer-term 10-year strategy that will make the farm more efficient in reducing GHG

or resource use. Breeding and herd improvement will be a big part of it, with the goal being to create high levels of production within a shorter lactation period, because we are having drier autumns.

“While we would like to not import feed, that is affected by the weather and dry periods derail us. We are also planting more trees, in the hope that carbon sequestered in smaller woodlots will be able to be counted under HWEN; we are reducing N and managing our applications better, and thinking about lowering our stocking rate, and concentrating on longer living cows doing higher per cow production.”

George considers genetics are the most powerful tool the industry has, to sire daughters that emit less methane and the advantage of genetics is that any gains made are permanent and incremental.

Science, education and willingness are key, with the first thing being accepting responsibility and shifting your mindset, he says.

“The climate is changing faster than we are adapting our systems.”

In international trading, which is primarily where our production goes, George says there is a wider expectation in the marketplace that we do our bit for reducing GHG emissions per kilo of milksolids. It is his belief that by 2030 every food product will have a GHG footprint attached to it.

“As a sector the challenge for New Zealand farmers is that we need to make absolute reductions but at the same time we need to keep our footprint per unit of product low and improving. ”

“By watching and following the researchers and science, it would actually help destress what is a challenging problem – rather than letting the anarchy of emotion rule us.”

George is astute at looking at the big picture of agriculture in NZ, both globally and throughout history – and not just with regards to farming – but that is another conversation.

As dusk brings with it the chilly Autumn air, George remains in jandals, shorts and T-shirt. He hasn’t donned anything warmer – preparedness for global warming, or just a fully acclimatised farmer?