Modelling raises hackles

Recent weather events challenge some of the forecasting in a recent bank climate change report. By Karen Trebilcock.

The Westpac NZ Agribusiness Climate Change Report, from Lincoln University’s Agribusiness & Economics Research Unit, has already proved it might be ready for the bin only months after its release in late 2022.

The Westpac NZ Agribusiness Climate Change Report, from Lincoln University’s Agribusiness & Economics Research Unit, has already proved it might be ready for the bin only months after its release in late 2022.

As climate change-fuelled cyclone after cyclone pounded the North Island and for the third summer in a row a drought was declared in parts of Otago and Southland, it forecast the north and east of the country may become drier, and the south of the country may become wetter.

It also said trees planted on marginal land would improve soil and water quality and create “natural flood management”.

While local vegetable prices soared due to the country’s wild weather, it stated one of the opportunities created by the country transitioning to low GHG agriculture was “higher market prices resulting from climate-related disruption in global markets”.

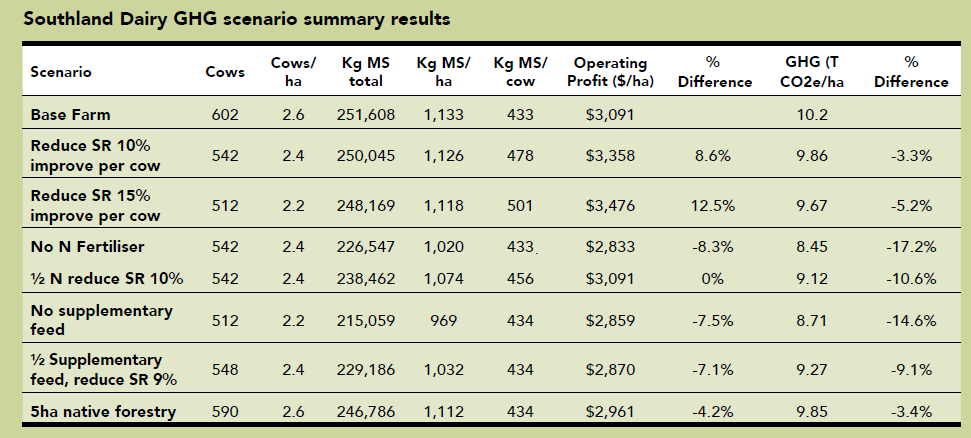

However, it was the report’s modelling of a Southland dairy farm’s GHG emissions by agricultural economist Phil Journeaux which has raised the hackles of those in the south.

Using Farmax software, he found reducing the stocking rate by 10% (from 2.6 to 2.4 cows/ha) and improving per-cow production cut GHG by 3.3% and increased profit by 8.6% with cows producing 478kg milksolids (MS) instead of 433kg MS.

Using no nitrogen, or no supplements, decreased GHG more but also significantly lowered profit by as much as 8.3%.

However, it said at lower stocking rates, maintaining pasture quality became harder and improvements needed to be made to current grazing management.

“While reduction in stocking rates is a key component of reducing GHG emissions, it has to be accompanied by an improvement in per-animal productivity in order to reduce/enhance the impact on farm profitability.”

Phil acknowledged the modelling didn’t account for situations seen in the last three summers in Southland where cows were fed less than half their diet in pasture with the rest made up of supplements such as grain and bought-in balage due to dry or drought conditions.

With no rain in the forecast, and if supplements were not able to be fed due to GHG regulations, southern farmers said they would be forced to dry off cows early in summer instead of in May.

“In my modelling I was assuming a normal year, so the elimination of nitrogen and bought-in supplement was being compared to this normal, not to a drought situation,” Phil said.

Southland Federated Farmers dairy chair Bart Luijten said it was important for southern dairy farmers to be able to use supplements whether it was for dry periods, snow days or cold and wet springs.

“We need the ability to use imported feed when our grass is not growing at the rate we need it to,” Bart said.

“The last thing we want to do is to starve our cows to meet our greenhouse gas emissions obligations.”

Southland dairy farmers were already excellent at per-cow productivity with a higher per-cow and per-hectare production than in many other regions. If they could improve it further they would be doing it now, he said, whether it lowered GHG emissions or not.

“I kind of hope we will get some technologies soon that reduce our greenhouse gas emissions so such drastic measures as destocking or reducing fertiliser or stopping imported feed won’t be needed.”

Imported feed and grass grown onfarm then harvested and stored should be treated the same.

“Sure, we can lower our stocking rate, but that just means we have to make more balage or silage or hay to keep grass quality, and that all burns diesel so what’s the sense in that? It’s a bit contradictory.”

Southern dairy consultant Howard de Klerk said he was tired of hearing how useless farmers were and that they couldn’t manage pastures and feeding supplements at the same time.

“In my experience, farmers have adapted way faster than their industry leaders and scientists.

“Our farmers are business people. They know the focus should always be on harvesting as much pasture as possible and then using supplements to improve production per cow.

“This has proved more profitable while also lowering GHG/kg MS but industry leaders continually ridicule this system.

“Obviously the amount of GHG produced per cow is more in a higher-producing cow compared with a lower-producing cow but the GHG produced per kg MS is significantly lower.

“It’s the same as per-hectare. The more grass a hectare grows the more GHG will be produced per hectare.