Dairy farmer, former rural banker and Lincoln University farm management lecturer Marvin Pangborn shares his family’s story of dairy farm development and what’s amounted to almost $1.7 million worth of upgrades to improve environmental outcomes on their Canterbury farms. He’s done so in the hope of shedding light on what’s been behind dairying development in the region and importantly the efforts that are well underway to meet ever-increasing environmental regulations.

Alderbrook Farms started as a 50/50 sharemilking partnership in 1987 with 450 cows on 200 hectares of border dyke irrigated land on the north bank of the Rakaia river.

Over the past 30 years, two farms were bought and converted to dairy farming and support land leased and developed.

The farms now total more than 500ha, carry 1200 cows plus 300 replacements and produce 6,400,000 litres of milk or 590,000kg milksolids (MS).

These farms will employ seven people this season. Before irrigation and conversion to dairying, the farms produced a few thousand lambs and partially supported two families.

There are many negative comments from the general public about the removal of trees on farms – but, their removal is a necessary to allow the more efficient systems to be installed.

Before the 1980s, dairy farming was a minor agricultural industry in Canterbury, occupying about 20,000 ha.

Most farms were near cities and provided ‘town milk’ but by the 2016-17 season the area used for dairy farming had grown to more than 271,102ha.

While the reasons for growth were many, the main influence was the lower profitability in the sheep and cropping industries. Concurrently, advances in irrigation technologies allowed more land to be irrigated.

Dairy farms established in the 1980s and 1990s were primarily based on either flood irrigation from nearby rivers or spray irrigation from wells with the water applied by ‘Roto-rainers’.

Although relatively cheap to operate, these systems would apply 50-100mm of water at each irrigation event.

The industry and regulators at the time did not perceive potential problems with pollution from dairying or nitrogen leaching from these systems.

During these years, no consents were required to establish a dairy farm and consents to spread effluent on land were not required if herds were under 400 cows.

There was no requirement to store effluent – it could be spread after each milking.

Although irrigation consents stated an average rate of abstraction, there was generally no limitation on the total amount of water that could be used and often there were no flowmeters to record usage.

Weather forecasts of rain events were far less accurate than today, so irrigation often occurred without a knowledge of soil moisture requirements.

Under this regulatory environment, with dairy farming offering a much higher return than alternative farming, the industry developed very quickly.

However, by the turn of the century, concerns were being expressed about the allocation of both surface water and ground water and the effects of these abstractions on the water resource. Additionally, scientists identified that the concentration of nitrogen in the urine of cattle was very high and the ‘light soils’ of Canterbury had the potential to leach this nitrogen to underground waterways. Most farms did not fence stock from waterways.

From the early 2000s, Environment Canterbury (Ecan) acted to exert more control over irrigated agricultural development.

A moratorium was placed on new irrigation takes in sensitive areas. Many water consents were recalled and in conjunction with farmers, Ecan established annual volume limits.

Livestock on dairy farms were to be fenced away from waterways and flowmeters to measure water usage became mandatory.

Later, all dairy farms needed effluent consents and large storage facilities so effluent did not have to be applied in wet weather. Soil moisture measuring devices were encouraged.

Now nearly all fulltime farming operations regardless of system need a consent to farm from the regional council.

Along with this consent, the farmer must prepare a Farm Environment Plan (FEP) and nutrient budget using the Overseer modelling tool.

These plans are audited for compliance after the first year, with further audits based on performance.

In the Selwyn-Waihora zone (where Alderbrook is located), if the FEP plan audit is considered to reflect Good Management Practice (GMP), the farm may receive an ‘A’ and will not be audited again for three years.

If GMP is not quite attained the farm will receive a ‘B’ and be audited in two years and if a “C”, it is audited annually.

Preparation of documentation for Alderbrook farm’s audit took more than 40 hours and cost $10,000 in fees to consultants, the auditor and Ecan.

In addition, farmers in the Selwyn-Waihora zone are required to reduce nitrogen leaching by 30% by 2022 from the 2009-12 baseline leaching as predicted by ‘Overseer’.

Like other farms in the district, Alderbrook Farm has invested in infrastructure to reach this target.

Before the onset of the consent requirement, Alderbrook Farm began to make changes.

In the late 1990s, cattle were fenced from waterways. In the early 2000s, soil moisture meters and flowmeters were installed.

Since, then there have been many system upgrades including replacing border dykes with pivots and solid set systems, water storage and effluent storage.

To accommodate the new, more environmentally friendly systems, shelterbelts have been removed, tracks moved and the farms re-fenced.

There are many negative comments from the general public about the removal of trees on farms – but, their removal is a necessary to allow the more efficient systems to be installed.

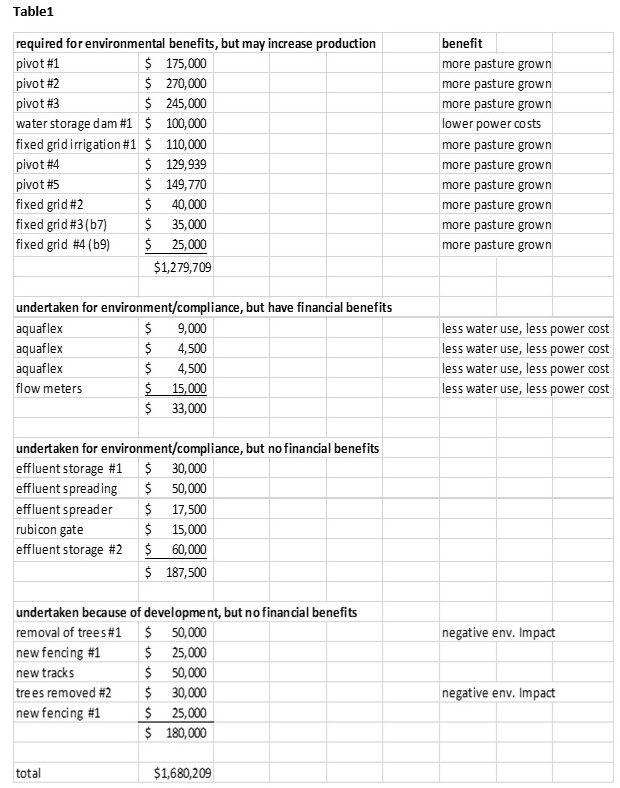

The table outlines the improvements made and their costs which total nearly $1.7m.

In the current season a further $300,000 will be spent on improved irrigation technology.

To be fair, some of these costs improve business efficiency.

For instance, replacing border dyke flood irrigation with pivots will not only reduce water usage and nitrogen leaching, but in nearly all cases increase the production of pasture.

In the past season, the former border dyke land used 60% less water under pivots than in the past. The installation of moisture meters allows farmers to time irrigation events to the actual need of the plants for water, thus saving power costs.

In the table, improvements have been categorised as to whether they have benefits besides improving the environment or were just for environmental reasons.

Pleasingly, most of them have economic benefits in addition to helping the environment.

However, what are not often accounted for are the other costs that accompany the changes. For instance, replacing border dykes with pivots, usually means re-fencing the paddocks and often the construction of new cow tracks.

What needs to be understood by non-farmers is that most Canterbury farms were developed under what was ‘good practice’ at the time. Rural communities have grown and prospered due to the installation of irrigation and the intensification of all agricultural systems.

The ‘negative externalities’ of the irrigation of the Canterbury Plains and the growth of the dairy industry were not foreseen by government, councils, communities and farmers. In most cases, farmers are making progress to reduce their environmental effects, but as this report shows progress takes time and involves a large degree of capital investment. Unfortunately for farmers, there is no end in sight to achieve what appears to be a moving target.