The proposed annual cap on N application will be difficult for some farmers and may not have the desired effect, as Anne Lee reports.

The government’s national 190kg/ ha/year cap on nitrogen has rung alarm bells in the rural sector – not necessarily because of the number itself but because it heralds a much-feared shift towards input controls.

It’s in stark opposition to the essence of the effects-based Resource Management Act where output limits are set on the effects an activity has – for instance, the amount of nitrogen potentially leached – leaving farmers to innovate, manage their inputs, or adjust their systems to achieve the output limit.

Both the Minister for the Environment David Parker and Minister of Agriculture Damien O’Connor warned farmers last year when they attended meetings about the proposed Essential Fresh Water Package they should be careful about their opposition to proposed output limits such as dissolved inorganic nitrogen (DIN).

The alternative, they warned, would be input controls and no one wanted to see that, O’Connor said.

But, despite the cap not being part of the proposal, the input control has found its way in while the DIN limit is to get more investigation.

Nitrate toxicity levels were tightened for fresh water bodies so that 95% of fish species cannot be affected by nitrogen levels rather than the previous limit of 80%.

That’s likely to translate into nitrate toxicity level well below the 3.8g/m3 level DairyNZ submitted, and may mean even tougher reductions in nitrate leaching limits for regions where farmers are already working towards significant cuts.

The nitrogen fertiliser limit in itself has been viewed as missing the mark when it comes to improving water quality standards.

Ravensdown predicts it will affect about 30% of farmers around the country with most of them in Canterbury.

Nitrogen leaching into underground aquifers is the issue in that region, with the major source being cow urine.

And while lowering nitrogen applications will reduce pasture growth and potentially cow numbers, farmers can simply replace nitrogen with supplementary feed to maintain stocking rate.

Some higher users of nitrogen have also shown well-timed, strategic applications coupled with well managed irrigation can mean less nitrogen is lost to groundwater than from those applying less in a poorer-managed system.

The cap could be seen as a nod to Greenpeace’s call for an outright ban on synthetic nitrogen fertiliser.

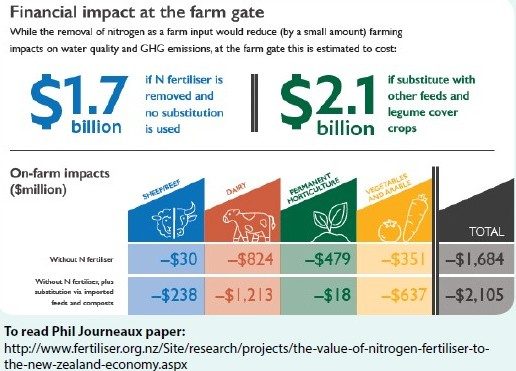

AgFirst agribusiness consultant and analyst Phil Journeaux’s November 2019 study into the value of nitrogen fertiliser to the New Zealand economy found the removal of nitrogen fertiliser would cause $19.8 billion drop in output, a cut in GDP of $6.7b, and a cost to dairy farmers of $824m.

If dairy farmers bought feed in or imported composts to replace nitrogen fertiliser inputs the cost rose to $1.2 billion at the farm gate.

Ravensdown’s general manager of innovation and strategy, Mike Manning, says precision and efficiency are the watchwords farmers think about now when it comes to fertiliser.

Putting on exactly what’s needed in the right place at the right time is a win:win:win for farmers because it not only means they get a better feed response to any application, they also save money and achieve better environmental outcomes.

Farmers have made their own moves towards using less nitrogen over recent years but that’s been driven by efforts to reduce its effects and has been but one tool in a multi-factorial tool box within the farm system.

“A cap is a blunt instrument and they’re often ineffective. There’s a risk they’re seen as a target not a limit, or it’s potentially simply replaced with other inputs, which means the end goal of reducing outputs isn’t achieved,” Manning says.

There’s been a strong uptake of coated urea technology as a means to get both the best plant response for nitrogen applied and minimise losses to the atmosphere through volatilisation, he says.

The urease inhibitor coating slows down the conversion of nitrogen from the dissolving urea particles to ammonia gas.

“We’ve also seen a lot more farmers using best practice when it comes to more precision.

“They’re not applying nitrogen in gateways, on effluent areas, around troughs – if there’s enough nutrient there then it makes sense not to waste money putting fertiliser on and it reduces potential losses to the environment.”

Manning says innovation and technology are bringing new efficiencies and, in the future, it may be that farmers “dial up” the coating for their particular situation such as a greater amount of the inhibitor coating on urea through the summer.

Already the co-operative has developed technologies to allow specific trace element coatings to be added to products such as superphosphate, including molybdenum, cobalt, and copper.

“They’re customised for a farmer’s specific needs on specific soils and they’re adjusted depending on the rate of the main fertiliser going on.

“For instance, if they’re putting on a low rate of superphosphate then there will be a higher rate of the trace element in the coating to achieve the desired rate of the trace element.

If a higher rate of superphosphate is going on then the rate in the coating will be lower.”

Nutrient input caps stifle these kinds of innovation, and overseas experience of input caps shows they often don’t achieve the environmental outcomes needed, Manning says.