Grazing cows in winter on fodder beet has been shown to significantly reduce nitrogen losses onfarm. Story and photos by Karen Trebilcock.

Fodder beet has been shown to reduce nitrogen losses during winter and early spring, a DairyNZ-funded trial at the Southern Dairy Hub has found.

Fodder beet has been shown to reduce nitrogen losses during winter and early spring, a DairyNZ-funded trial at the Southern Dairy Hub has found.

Research has shown the grazing of brassicas during the 10 weeks of winter when cows are dry is when large nitrogen losses can occur from soils in the south.

Dung and urine deposited as winter crops are grazed, and the soil then left bare until sowing in October or November, causes nitrogen to leach into waterways instead of being used by a growing plant.

As well, winter and early spring is when there is the most rain, making the problem worse.

Researchers Ross Monaghan and Chris Smith, both of AgResearch, spent three years sampling porous ceramic cups, which collect leachate, after winter crops on the research farm near Invercargill had been grazed or harvested.

“It was thousands of samples that were analysed,” Ross, a senior scientist, said.

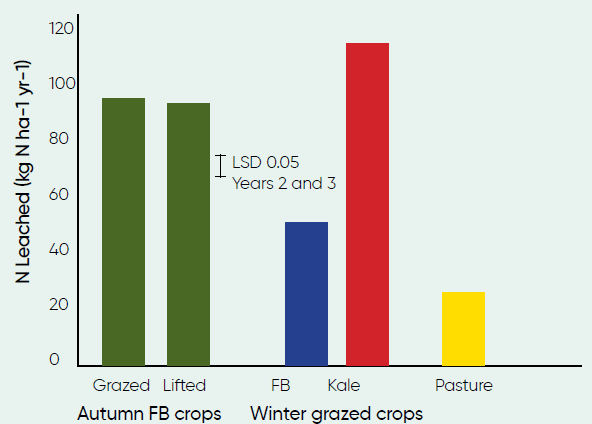

Compared with wintering on kale, it was found cows on fodder beet would cause about 50% less leaching of nitrogen into waterways. Earlier trial work had shown cows eating fodder beet have less nitrogen in their urine than cows on more protein-rich feeds such as grass or kale.

The lower nitrogen, or crude protein content, of fodder beet, contributed to the lower losses.

“Our work supported the hypothesis of cows eating less nitrogen per cow per day resulted in less nitrogen in their urine.”

Another factor was the less land required to winter on as fodder beet crops grow more drymatter per hectare than kale.

As well, Ross said, the soils in the fodder beet paddocks were more compacted due to the higher stocking density which may have caused the nitrogen to become a gas rather than be leached into the soil profile.

All the leaching did not occur in the winter as the crop was fed. The research found winter-deposited urinary N took 12 to 16 months to leach below the 600mm depth of the ceramic cups, peaking the following autumn and winter.

Compared with the hub’s total N loss for the year, if only fodder beet was used for the 10 weeks of winter, it would contribute 33% of the farm’s loss. If kale was grown as the winter feed, it would account for 50% of the farm’s N loss to water.

“This highlights the large contribution of winter crop grazing to N leaching losses from these types of dairy production systems.”

Ross said no roots were found to extend to the 600mm drainage zone.

“At that depth the soils were quite tight. It was hard work digging down to that level.”

The study also looked at autumn-lifted fodder beet with the ground left bare afterwards through the winter until soil conditions allowed it to be resown in late spring.

“This practice was expected to reduce urinary N returns to the plots, and thus leave less N in soil that would be vulnerable to transport in the drainage,” he said.

However, it was not the case with observed leaching losses remaining relatively high.

“It suggests that urinary N returns were less important in the autumn fodder beet treatments than we anticipated.”

Instead, the residual soil N that had not been taken up by the crop when it was growing was leaching, due to the soils being left bare in late autumn, winter and early spring.

“Our findings indicate that any benefit arising from a reduction in urinary N excretion due to feeding fodder beet in late lactation was outweighed by the risk posed by leaving soil bare over the following winter.

“It shows how leaky bare soils are.”

If fodder beet was planned to be lifted or fed in late lactation it should be done at a time when soil conditions and temperatures allowed another crop or pasture to be planted in the paddock before winter.

Ross was not sure why there was so much nitrogen left in the soil in the hub paddocks when the fodder beet had been lifted.

“Maybe the amount of fertiliser applied following the recommendations was over cooked, or maybe it was from a flush of N from the pastoral soil that had been cultivated when the paddock was sown with fodder beet.”