The moral injustice of the M bovis eradication programme.

In the second part of a series on Mycoplasma bovis, ag scientist Nicola Dennis investigates the science of human trauma.

We are back looking at the lessons left unlearned from New Zealand’s largest livestock disease eradication programme. This time we are stepping into the social sciences to explore the moral injuries incurred with Chrys Jaye, Geoff Noller, Mark Bryan and Fiona Doolan-Noble. They are the social science team who brought us not less than four (and counting) science papers on the psychosocial impact of the Mycoplasma bovis( (M bovis) programme.

We are back looking at the lessons left unlearned from New Zealand’s largest livestock disease eradication programme. This time we are stepping into the social sciences to explore the moral injuries incurred with Chrys Jaye, Geoff Noller, Mark Bryan and Fiona Doolan-Noble. They are the social science team who brought us not less than four (and counting) science papers on the psychosocial impact of the Mycoplasma bovis( (M bovis) programme.

In their papers, the group points out that it’s not their intention to add to the voices of criticism about MPI’s handling of M bovis. We’ve all been there, done that, and got the apology. The point is to work out where it went wrong, so there can be better outcomes next time.

Although, it was hardly a lack of literature holding MPI back.

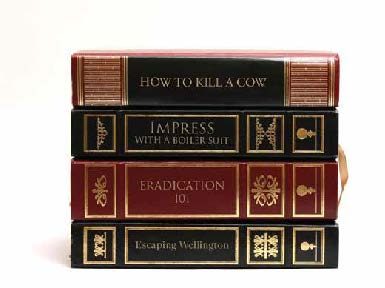

Fiona holds up a text book titled Animal Disease and Human Trauma: Emotional Geographies of Disaster. Oh snap, literally there are text books on how to treat farmers during disease eradication. The required reading list will have grown a few inches by the time this team is done. Before we get into their M bovis findings, let’s work out what social science is.

What is social science?

I’m from the data science world, where an extrovert is someone who will look you firmly in the shoes when they talk to you. I’m sure most of my colleagues chose their career with the intention of never using the telephone for its intended purpose. But social scientists have to be social. It’s in the name.

Social (a.k.a. qualitative) research involves interviewing people and then studying the answers. Don’t picture the standard customer service questions such as “on a scale of 1-10 how likely are you to recommend M bovis to your friends”. They ask open-ended questions carefully chosen by a panel of researchers (and their mentors from their stakeholders and governance groups) to prompt participants into talking freely about what has happened. I don’t think they ask the questions in any particular order either, I think this is one of those mythical, human conversations that elude the rest of the science world.

Interviews are recorded and transcribed (written down) and any information that could be used to identify the participant is removed. Transcripts are then sent back to participants in case they wish to add or clarify anything. Then, the transcripts are studied to pick up patterns.

The social scientists pick through their bag of philosophical theories and anthropological frameworks to gain a deeper understanding of what is happening.

“That’s the bit that most people overlook,” Chrys says. “We aren’t just reporting on what was said, there is a lot of analysis going on behind the scenes.”

I ask the group to explain some theoretical frameworks to me and it doesn’t take long until my brain starts flashing error messages. Let’s explore a few of the concepts and their relevance to the M bovis eradication programme.

KEY CONCEPT 1: MORAL DISTRESS

Remember when Lady Gaga was ‘Caught in a bad romance’? Well, moral distress is when you are caught in a bad plan. If you were free to do what you believe is ethical, you would do something very different to what you are being made to do. Your moral fibres are screaming for you to move the heavily pregnant cows out of the mud, but the boffins are forbidding any cattle to leave the farm. The petfood company is mowing down your milking cows in the yard in front of your weeping staff like a Quentin Tarantino movie… but MPI is threatening to call the police if you don’t allow it.

Moral distress is particularly relevant to veterinarians, not just in M bovis eradication. The social scientists tell me it is a burning issue in the daily life of the rural vet. Doing what they believe is right for their patients is often constrained by the owner’s finances or willingness; by medical limitations; or by commercial reality for production animals.

KEY CONCEPT 2: EPISTEMIC INJUSTICE

This is another version of being caught in a bad plan. This is when you have information or expertise you believe would improve the plan. But nobody in charge is going to put any stock in what you have to say. You are watching MPI spend $150k dismantling an old cow shed for cleaning, when you know that it would only cost $80,000 to knock it down and build a new one. But, no new shed for you, it’s none of your business how MPI spends its decontamination money, thank you very much.

Epistemic injustice seems to be a major symptom of a centralised system (see also lifeworlds). Over and over again, the people in Wellington could not hear the voices from the people on the ground.

It seems like things have improved lately with more regional coordination in the M bovis programme. But, it also seems like every programme begins with the ministry jamming its fingers into its ears. I’ve heard grumbles about the contingency planning for foot-and-mouth disease. It’s too soon to start poking holes in that. Instead, I will refer you to the historic West Coast heifer lump debacle – a curious case of governmental belligerence that burned for decades (see timeline next page).

KEY CONCEPT 3: LIFEWORLDS

The farm isn’t just a business, it is a home. Farming isn’t just an industry, it is a community. Or in the words of the social scientists, there is a farm “lifeworld”. Everybody else has a lifeworld too, you aren’t special.

Within our farm lifeworld, we mostly interact with people like us who share the experience of praying to the pasture gods and religiously following the farming calendar. We have a shared understanding of how things are done and the interlinking practices needed to keep our lifeworld turning.

The beauty of the lifeworld is that it allows you (the inhabitant) to ponder the whole shebang without breaking your brain. Habermas, the social theorist who came up with the lifeworlds framework, argues we are really only capable of considering one thing at a time. So in order to reason and communicate with each other in the lifeworld, we must have a shared understanding of all the things we are taking for granted while we discuss one aspect of it (such as culling dates).

You can have deep conversations with someone else in your lifeworld about any ONE aspect of farming, because you have a shared understanding of all the other things that are going unsaid. You can’t discuss all aspects of the lifeworld at once, so you can’t achieve the same level of communication with someone who doesn’t know that bulls are the ones with balls.

Over in Wellington, there is a whole other lifeworld – a world of rules and policy documents with 37.5-hour working weeks and Christmas office shutdowns. This in itself caused a clash because farmers were often too busy to catch MPI during office hours. Farmers couldn’t understand why MPI had declared it had found M bovis for the first time in Southland (December 2017) and then promptly shut up shop for three weeks over the Christmas holidays. In our lifeworld, it is taken for granted that cows come before chrissy presents. Over in their Ministry lifeworld, I am sure there were frustrations with farmers who don’t have the foggiest about policy and bureaucracy.

KEY CONCEPT 3.5: COLONISATION OF THE LIFEWORLD BY SYSTEM

I may never truly understand what “colonisation” means, but I will give this a go. Bureaucratic systems are fine, necessary even. But, they are set up to limit communication. Rules and processes are devised so that there isn’t endless discussion. But once you have a system in place, then communication within the system is kind of limited to “press 1 if you want to speak to accounts”, “press 2 if…”. And there is no room for any ideas that might break the system. The system protects itself.

The M bovis system attacked the pillars of the farm lifeworld. It disregarded the farming calendar we all live by. The system was more important than animal welfare concerns such as killing heavily pregnant cows. The system was more valuable than the farm lifeworld’s mantra of efficient use of feed, animals, and money. There is a general acceptance that the M bovis system did get better over time. But elsewhere we hear the mangled cries of the lifeworld as it gets chewed up by other systems. Sounds an awful lot like Groundswell revving their tractors.

KEY CONCEPT 4: THE MORAL ECONOMY

The moral economy speaks to the fact that money isn’t the only thing being traded in the farming industry. There is a form of moral capital that is accrued or eroded while interacting with each other.

Reputational moral capital is a relatively easy one to grasp. How you conduct yourself, the health of your livestock, the pleasantness/productivity of your property, and whether or not your driveway is stacked with white, government utes… these all speak to your reputation as a “good farmer”. The stigma of being labelled a “bad farmer” is obvious. As is the stigma of being labelled a “morally bankrupt” or “toxic” ministry.

Reputational capital was a big deal for farmers under “active surveillance”. These were farms that were being tested as part of disease tracing, but were not yet confirmed to have received animals from an infected property.

The net for active surveillance was cast very wide, and these farmers were advised to keep their status to themselves and remain trading cattle as usual. This pitted the farmers’ reputational interests against their financial interests. Reputationally speaking, it is bad form to carry on as usual knowing you may infect your clients, neighbours and graziers. But, active surveillance farms were not eligible for monetary compensation if they proactively stopped transporting cattle.

Unfortunately, participants in the study also identified compliance with MPI as a form of moral capital. They realised that if they kept their heads down, then their punishment would be less severe. At least one participant claims MPI threatened to withhold compensation entirely. Another farmer recounts their bank foreclosing on the farm due to concerns about compensation – “they didn’t know whether MPI was going to kill $3 million-worth of stock and not pay anything. The last thing the bank wanted to do was give us money”.

The last form of moral capital to discuss is the value of an ethical death. Culling cattle is part of the farming gig. Many of us find it distressing, but we can justify it. Culled cattle are either at the end of their productive life and are therefore being spared the pain and distress of a natural death. Or they are freeing up resources and bringing in much needed cash for the greater good of the entire farming operation.

Culling part of the herd is business as usual, but culling a whole herd because they might be unwell is an entirely different moral reckoning. The researchers found that “the lives lost to M bovis were considered morally wasteful, and this explains why so many participants viewed MPI culling as immoral”.

CONCLUSION

That is the end of the anthropology homework. Now we have some fancier words to describe what we see. Fancy words come in handy if you find yourself continually referring to Nazis every time the bureaucratic steamroller passes by.

At the end of the day, our social science superstars recommend similar things to what we have heard before. That MPI needs to have a better relationship with the sector. They need regional interdisciplinary groups on the ground with better local knowledge and leadership skills. They need to talk with communications and behavioural experts. And they need to read the damn textbooks (and now some new scientific papers) on disease eradication.

I am sure that MPI will be thrilled to find themselves within the required reading list. When they are done pumping out papers, our social science friends intend to incorporate their findings into a new textbook on the topic.

The West Coast heiferlumps problem

Have you heard of the heiferlumps?

To the uninitiated, it sounds like a tale from Winnie the Pooh. The one in which the Department of Agriculture (the MPI of the day) spends four decades gaslighting farmers about the accuracy of the bovine tuberculosis (TB) test. Let’s follow the Department’s roll out of the caudal fold test for TB. That is the ”jabbing the tail and returning a few days later to see if there is a lump” test that all cattle owners should be familiar with.

1922 The TB test becomes available for voluntary use in New Zealand. Uptake is poor because the compensation offered is below market value and farmers are unhappy with the rate of false positives. About 10% of cattle are reacting to the test (indicating disease), but in many cases there is no TB found when the animal is slaughtered.

1945 NZ makes it compulsory to test dairy herds for TB, but not for real. So unpopular is the test that it will still be another 16 years before it is anything but voluntary.

1952 The first formal plan for bovine TB eradication shows that the department largely views the poor acceptance of the TB test as an issue with farmer education. Public demonstrations of the caudal fold test commence.

1961 The TB eradication programme begins in earnest, slowly rolling out around the country.

1963 The West Coast is furious. An unreasonable number of cattle are testing positive for TB, but upon compulsory slaughter, they are healthy. A veterinarian working in the area points out that the issue is in West Coast heifers. These heifers are prone to “heiferlumps” – they get the tail lump associated with a positive result, but they don’t have TB. He says heifers with lumps should not be slaughtered, rather re-tested in six months time. This helpful suggestion, which would eventually be adopted 14 years later, earns him disciplinary action from the department. In August, the Minister of Agriculture is served a petition from West Coast farmers demanding an investigation into the heiferlump issue. A few weeks later, the West Coast farmers go on strike and refuse to test their cattle. By October, the Minister of Agriculture announces that the TB eradication programme is suspended while an investigation commences.

1963-1964

The investigation takes place. The Department commissions Flock House agricultural college (in the North Island) to test, slaughter and inspect 550 cull cows from around the regions. I’ll take a second to remind you that the problem was with West Coast heifers, not everybody’s aged cows. The results of the Flock House experiment confirmed, to the department at least, that the test was working as expected. The department convinces itself the problem is “troublemakers” and “farmers that are not prepared to listen to logical arguments”. Farmers are warned that their pesky complaints are putting the entire scheme in jeopardy. If that happens, NZ might not be able to compete on the international market and “the economic situation will be grave”. That old chestnut, eh?

1967 TB is still rampant on the West Coast. Poor clearance rates of TB in West Coast dairy cattle mean all cattle over six weeks old are on three-monthly testing. All reactors are immediately slaughtered. This definitely seems like a step in the wrong direction for a test that has questionable reliability in young stock.

1971Trials on the West Coast confirm possums are a vector for TB. It’s unclear if possums are offered as a scapegoat for the ongoing West Coast testing issue.

1974 Changes in staff meant there are now people with epidemiology training overseeing the West Coast issue. The new Regional Veterinary Officer for the West Coast returns to Wellington to present statistical evidence that the heiferlumps problem is real and it is “wiping farmers out”. There are some compelling theories about why the West Coast might be different. Could it be Mycobacteria in West Coast moss sensitising heifers to the TB test? Biological stresses from the wet climate? We have our own heiferlump issue in my area caused by a cross-reaction to avian tuberculosis from a plague of geese, I think that is a possibility. But at this point, I haven’t been born yet. My belated thanks goes to whoever made sure my heifers aren’t annihilated in the present day.

1977ish The department relents to “the West Coast rules” where any cattle under three years old that reacts to the caudal fold test may remain upright until retesting six months later. This goes on to save 70% of heifers that test positive. It is also decided someone should kill all the possums.

1985 Sam Jamieson who ran the Department of Agriculture during the “West Coast farmers be crazy” phase reveals he has no regrets about the handling of the issue. “After the storm is over, is there value in looking for the wind that caused it?” he asks. Nice side step, but everyone smelt where the wind came from.