Anne Lee

While the latest Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ) financial stability report shows some minor headway being made in the reduction of potentially stressed loans the number of loans deemed non-performing by the major banks is on the rise.

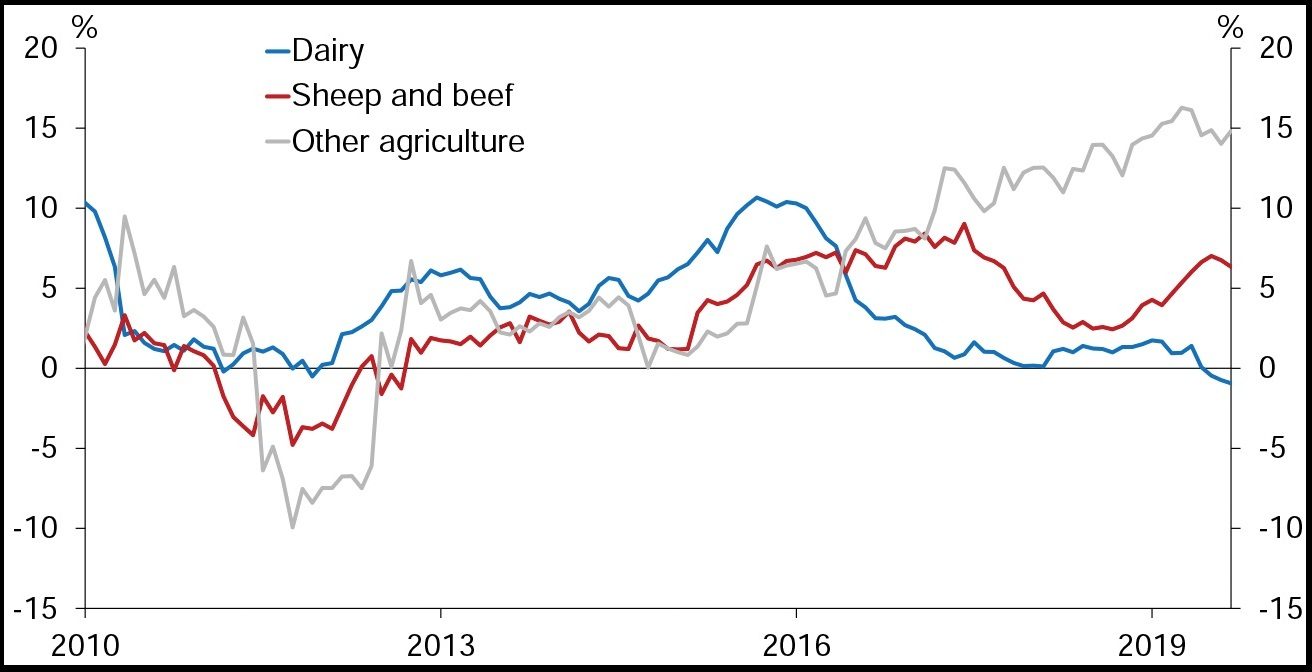

The report, released shortly before the RBNZ announced its Capital Review Decision, in early December shows dairy sector debt decreased by 0.9% in the year to September reflecting the banks’ reduced appetite to lend to the sector and a decline in demand for new loans.

The report noted banks expect to tighten credit availability further of the next six months.

That’s due in part to a desire by the banks to diversify agricultural exposure and a re-evaluation of lending portfolios to manage the transition to higher capital levels.

The dairy sector has a high debt-to-income ratio at 350%, and debt in the dairy sector is concentrated, with 30% of debt held by highly indebted farms – those with greater than $35 of debt/kg milksolids (MS).

The fact some dairy farms remain vulnerable, despite most being profitable over the past three seasons, is reflected in the rise of non-performing loan ratios particularly in the past year.

Highly indebted farmers remain particularly vulnerable to shocks such as a price downturn or an unexpected increase in interest costs.

Environmental regulations are also likely to increase compliance costs and Fonterra’s financial issues raised concerns over its ability to provide a dividend income stream to its shareholders in coming years, the report says.

It suggests banks may move to reduce the availability of standby facilities that carry ongoing capital requirements irrespective of drawdowns and to raise interest rates on riskier loans.

The move by a number of banks to reprice higher risk debt means the most financially vulnerable farms are unlikely to see significant relief in their financing costs.

Tighter restrictions on foreign investment may reduce demand for dairy farms and there are limited options for highly indebted farmers to address that debt.

Banks are also seeking to raise margins by imposing fees for various facilities.

‘While it is important that banks seek to manage their own exposures to the dairy sector from a systemic risk perspective, it is also important that they continue to work constructively with farmers wherever possible.’

“While it is important that banks seek to manage their own exposures to the dairy sector from a systemic risk perspective, it is also important that they continue to work constructively with farmers wherever possible.

“The current profile of dairy debt reflects a degree of poor decision-making by borrowers and lenders, but it is important that banks are not overly cautious when implementing new lending policies.

“Lending always entails a degree of risk but excessive risk aversion by financial institutions when risks crystallise can introduce unnecessary pro-cyclicality into the system, and despite the challenges in the sector, most operations will continue to be viable investments unless payouts decrease significantly.”

While banks have widely touted the RBNZ’s Capital Review as a factor in changes to their banking arrangements with some clients RBNZ governor Adrian Orr was at pains to point out banks had been adjusting how they view and handle some dairy debt well before the capital review.

“Nothing here (in the capital review) relates to the risk allocation of capital, it’s about the level of capital – I’m a bit tired of having to say it.

“Some banks are highly exposed to the rural sector and they have been making decisions irrelevant of what we are doing.

“Lending into the agricultural sector is still strongly positive – it’s only a part of the dairy sector that’s highly negative and that is for a specific idiosyncratic set of reasons established by banks and borrowers. That’s the nub of it.”

Orr says the changes shift the requirement for banks to hold capital from 10.5 to 18% for the larger banks to 16% for smaller banks.

The average banks actually held before the changes was 14%.

The RBNZ’s analysis showed banks could fund the increase over a seven-year period by retaining earnings and paying out 30% of profit as dividends rather than 70%.

The expected impact on interest rates would be 20.5 basis points or 0.2%, much lower than what had been predicted by banks and at the lower end of the scale of the RBNZ’s initial prediction.

Orr says that was due partly to changes from the initial proposal that allowed banks to hold a significant proportion of their capital as redeemable preference shares which allowed capital to come at a cheaper cost.

He noted that part of the reason for the tightening in capital requirements was due to the concentration of bank debt with so few major banking players and he would see it as a positive move if capital markets got broader in the offerings.

“Perhaps some of our rural sector would be feeling quite different if there was a broader range of options – longer-term debt and or equity than what has been historically available,” he says.