A 100% trading policy allows a couple to take advantage of opportunities and reduces the risks the region’s climate delivers. By Tony Leggett.

Playing to the strengths of the Hawke’s Bay farm he manages is paying handsome dividends for Hugh Abbiss, this year’s Silver Fern Farms Hawke’s Bay Farmer of the Year winner.

When he and partner Sally Terry arrived in July 2019 to take on the manager’s role at Totara Hills Station, they were encouraged to challenge the status quo by owners Mike and Caroline Rittson-Thomas.

The couple embraced the opportunity and three years on, the 785-hectare-effective farm has undergone a massive shift in policy, performance and profitability.

“I guess we were going in fairly blind, but we did put a lot of effort in to deciding what we had in terms of the property, looking at historical trading margins for stock, and thinking about the policies we wanted to focus on, particularly around the fit with the cropping programme,” Abbiss says.

The couple identified the markets they wanted to be in, and that was predominantly lamb finishing, carry-over dairy cows (a major one), store-to-store cattle trading, buying in late winter and selling late spring, and five-year-old ewe trading.

Once they worked out which livestock enterprises would suit, they developed a cropping programme and put a feed budget together, then adjusted the livestock numbers to match it.

That spits out their stocking rate.

“It’s adapted each year. For example this year we haven’t done any hogget grazing, but we’re back into cattle grazing. Last year was the opposite.”

An early casualty was the capital stock, all sold soon after they started the role. In its place is a 100% livestock trading and grazing enterprise, supported by a large-scale forage cropping and re-grassing programme.

Cash cropping remains on the 50ha of centre-pivot irrigated flats and adjacent dryland cropping area, much of it now grown on contract with local contractors.

The farm is managed in four distinct parts – dryland cropping flats, irrigated cropping flats, improved rolling country and unimproved hill country.

Each area is handled separately.

They’ve almost ring-fenced them and used feed budgets on them separately to optimise the grass they grow.

“It is one of our key principles we’ve focused on from the very start,” Abbiss says. “It drives us and leads our decision making.”

Each block has individual cropping, re-grassing programmes and the livestock.

The 100% trading policy allows them to take advantage of opportunities and also reduces the risks the Hawke’s Bay climate delivers.

“I don’t like saying we’re summer dry.”

Their biggest issue is variability and unpredictability.

“Yes, we can get a heap of rain and it can get very dry, but it’s not knowing what is going to happen in two months that is the biggest challenge for us.”

That’s why they have tried to design a system to handle that variability which allows them to grow as much grass as possible and convert it to the highest possible value in the livestock that graze it.

Abbiss concedes it looks easy when it’s numbers on an Excel spreadsheet and the real challenge is putting that into practice on the farm.

“We’re always adapting to grow feed and convert it. I focus on profitability, income less expenses, growing that farm surplus while taking into account the change in market value of the stock on hand.”

A key ingredient to their success is their deliberate choice to surround themselves with skilled professionals.

“This group is huge with this place, from agronomists to stock agents, to contractors. The phone goes nuts some days. There’s also my own team of course who I think buy in to what we’re doing here.”

Number crunching using Excel spreadsheets to evaluate livestock options and get that elusive close match to feed availability is a constant for the couple. Abbiss says the amount of analysis they do is a big part of the success achieved within the whole business to date.

He’s content to use Excel over other decision-support tools available.

With the support of the property’s owners, they kicked off a large regrassing, fertiliser and drainage investment in year one. Abbiss admits there were some challenging moments in achieving the level of change in such a short period.

“Our development expenditure was all cashflow funded, probably to the detriment of our first year’s performance.”

It was on the back of successive droughts, they were clearing out capital stock and getting cleaned out there.

“It was a rough enough year that didn’t quite go to plan and Mike probably was scratching his head a bit.”

But in year two, the development started to pay dividends and they achieved better margins than budgeted for by buying lambs and yearling cattle just as the area emerged from drought.

“We did go into it in the dark a wee bit, but I can’t stress enough how the change in livestock policies and banging through those short trades and cashing up that grass as fast as we possibly could made the difference.”

Stock that would deliver good profit

Hugh and Sally knew if they were going to throw all the inputs into it, they had to put on stock classes that would deliver good profit.

“Our lamb carrying capacity through the autumn has tripled so that certainly has helped us,” Abbiss says.

The new livestock policies were bedded in by year two (2020-21) and they continued with forage cropping and new grass at the same pace, also expanding the area in grain crops with contractors.

In the same year, a programme to fence off waterways was started.

Livestock policies were further refined in their third year and the focus shifted to developing value-add relationships with contractors, suppliers and other stakeholders to the business. This included taking on Wairere’s terminal sire Dominator ewe flock, which is lambed at Totara Hills, and once a selection of ram lambs has been taken out for future ram sales, the remaining lambs are finished on the farm.

Year three also included completion of 4.2km of waterways fencing and the regrassing, fertiliser and drainage area reached a status quo level. It was also year one of their profit share arrangement with the farm owners.

For the 2022-23 year, the focus is on driving great profitability from the investment already made in building fertility, new pasture and the value-add arrangements being developed. Reducing use of nitrogen fertiliser is also in their current year plans.

Gross farm income (GFI) per year has more than doubled since they arrived at Totara Hills.

“We never thought we’d get to where we are now when we started. An early aim was to do $1000/ha and we’ve gone past that now,” Abbiss says.

“We’re developing more land, and we’re opportunity focused so we’ll keep looking. That’s our mindset.”

Hawke’s Bay farm consultant John Cannon says the best operators on this country are achieving GFIs of more than $3000/ha and some over $4000/ha, usually with a large component of cash cropping included.

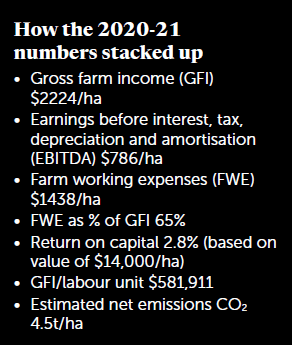

The Hawke’s Bay Farmer of the Year judges reviewed the 2020-21 financials when judging entries for the 2022 Award, but if those results are adjusted for increase in the value of livestock between opening and closing that year, the numbers spike up.

GFI goes from $2224/ha to $3400/ha, EBITDA moves up from $786/ha to $1611/ha and farm working expenses (FWE) drops from 65% of GFI to 47%.

GFI per labour unit was an impressive $582,000, well above the accepted standard for good performance of $500,000/unit.

Totara Hills traded 11,433 lambs in its 2020-21 year. Margins from sale price to next purchase price reflect the focus on shifting feed into higher margin periods of the year. The average sale to purchase margin for cattle was $677/head (selling at $1421 and buying in at $754). For sheep trading, the same margin averaged $56/head (selling at $168 and buying in at $112).

That lamb margin doesn’t reflect the impact of buying lambs in early winter to finish a few months after the balance date.

“For past three years, the cash we generate within a financial year is getting blown in the last three months as we restock at higher stocking rates and carry heavy lambs through balance date that don’t get realised in that financial year.

“So, that’s something we’re aware of and take into consideration as we analyse how we’re tracking,” Abbiss says.

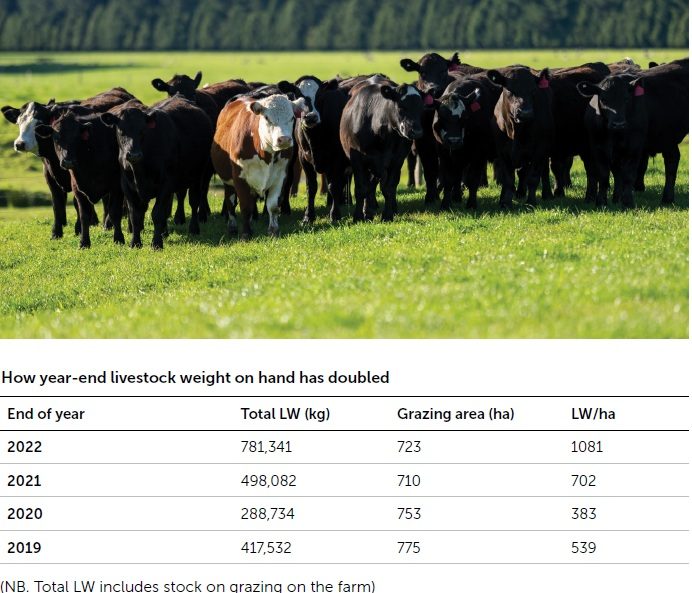

Total liveweight has doubled

Total liveweight, including grazing stock on hand, has doubled from 539kg/ha at balance date in 2019 to 1080kg/ha in 2022.

Wintering just over 1000kg/ha was challenging, especially as they were feeding at 3.5% of LW (average across all stock) to achieve weight gain rather than feeding at maintenance level, Abbiss says.

“It’s just something that happened with the increase in stocking rate. We’ve landed there. It’s not necessarily a goal to do that LW.”

Totara Hills is estimated to be growing 11,500kg/ha/year drymatter (DM) and produces just under 4.5 tonnes/ha of carbon dioxide emissions each year.

Its cash cropping enterprise made $3303/ha net income and grazing generated just over $300,000 of income.

Grazing cattle on contract over summer is a big reducer of risk for the business. Summer cattle trading is a less-preferred option in their risky summer-dry region, so they opt to graze cattle.

“It means we can stock up with trade lambs in the autumn because we know that grazing cattle are gone on a certain date. So, we’re not playing the market there.”

Cost is a constant focus in the analysis that goes into the forage and cash cropping programmes.

Abbiss says the total cost to get crops to the point of harvest increased 30% over the past year. Thankfully, cash crop returns have also increased by a similar amount.

The issue is their forage and new grass programmes.

“Our cost per kg DM grown for forage crops has gone up from about 8c/kg to 12–14c/kg. But, if you back yourself to generate a return of more than 30c/kg DM consumed from livestock grazing that crop, you’re still holding a good margin there.

“I’m still comfortable to do it – it fits the system we have in place and that is a big one, probably the number one.”

The forage crops and new grass also relieve the internal parasite pressure on young stock.

“The elephant in the room is managing those parasites as well, and those forage crops are just essential for doing what we’re doing.”

Abbiss doesn’t rule out changing the programme, especially if cost creep continues.

“I’m not too keen on changing it but will be watching our margins.”

In their first two years, they spent a lot of money on forage cropping but have refined how they grow them, and are more efficient.

“The biggest cost in growing forage crops is a failed crop and you have to do everything to avoid that. If it happens you drop $1000/ha cost and you’ve got nothing to show for it.”

Forage crops cut parasites

Large areas of forage crops are reducing the parasite challenge for lamb finishing and helping deliver high weight gains and higher carrying capacity.

About 130 hectares a year is going through a forage crop on a predetermined rotation. The crops are all direct-drilled and fill feed deficits in late summer and mid-winter, de-risking the livestock operation from the effects of lingering dry summers and creating the opportunity to take on big margin lambs over winter.

Abbiss says there are high returns for the taking when there’s a meat schedule lift combined with an increase in stocking rate and liveweight gains.

The forage crops transfer feed to autumn and then to winter which allows him to maintain the stocking rate required to maximise utilisation when the spring flush hits.

“We’re trying to harvest as much spring grass as possible then take out the crop area once those winter trade lambs leave the property,” he says.

“By taking out 30% of the farm from September, we focus our efforts on the 70% left so the team’s workload is reasonably stable.”

For the dryland flats, a typical rotation would start with coming out of kale and into spring barley, then pasture for 22 months, before returning to kale.

After harvest, this area is sown in a mix of 10-13kg hybrid ryegrass (Mohaka is a common choice), along with 5-7kg/ha of Italian ryegrass, plus clover and plantain.

By Christmas, ahead of the typically dry summer conditions opening up that sward, these paddocks are sprayed out and go into a brassica, most likely a kale. They will be grazed by young stock in late February and March, then shut up for winter grazing by lambs, before being sprayed out for barley again in the spring, then back to a pasture mix after harvest for the following 22 months.

On the rolling improved country, they have found a summer fallow works best ahead of re-grassing with four to five-year hybrid/perennial ryegrass and clover pasture mix. Annual grasses are performing well between grain crops for the 50ha of irrigated flats.

Forage crops are sown with 100-150kg/ha of DAP plus boron, and side dressed with 70-150kg/ha of urea, depending on their yield potential. Before the winter grazing by lambs, a second side dressing of urea at 50-70kg/ha is applied.

About 90ha of spring barley is grown on rotation around the dryland cropping flats and all 50ha of irrigated flats is sown into a mix of crops including maize silage, carrot and radish seed, peas and wheat.

Paddocks selected for barley receive between 2-3t/ha of ag lime before sowing.

Average feed cover on each block is assessed regularly by eye, and data is recorded in a spreadsheet. Abbiss says knowing demand is critical, especially when you can predict the growth with more certainty, like the period from when it rains in autumn to about October 1.

“We know we can predict with accuracy through that period, but after that we need to have significant flexibility in our system from October 1 to about the end of March, so that is when our policies will maintain that flexibility to cater for that time,” he says.