Opportunities with methane

Agriculture can be part of a climate solution, says greenhouse gases guru, Professor Frank Mitloehner. By Joanna Cuttance.

Professor Mitloehner leads the CLEAR Center at University of California, Davis, and he told an audience at NZ’s Lincoln University that by carefully choosing which methods of managing methane from livestock to use, opportunities could be created to help reduce global warming.

Professor Mitloehner leads the CLEAR Center at University of California, Davis, and he told an audience at NZ’s Lincoln University that by carefully choosing which methods of managing methane from livestock to use, opportunities could be created to help reduce global warming.

“Methane is the Achilles heel on one side, but it is also a real opportunity on another side,” he said.

The agriculture sector in Mitloehner’s home state of California developed an opportunity that not only reduced methane, but added another revenue stream and helped the transport sector.

Californian law mandated a 40% reduction of methane to be achieved by 2030, which was below 2013 thresholds. With incentive-driven support, innovative ideas were developed and implemented.

For example, dairy farmers are covering their open lagoons, which are used for storing manure. The covers trap biogas emanating from that manure and 60% of this gas is methane. The biogas is taken, cleaned up and converted into renewable natural gas that’s used for fuel in heavy duty trucks and buses.

Farmers doing this have made money from it, and the sector was well on its way to achieving the 40% reduction of methane by 2030 as asked for by the Californian policy makers, Mitloehner said.

Mitloehner said NZ would need a different approach to make a meaningful contribution to the climate scenarios, as California was significantly different from NZ. Agriculture in California was very intensive and very large scale; a farm with fewer than 500 cows was not financially viable. However, lessons could be learned from each other, he said.

Mitloehner suggested a matrix fit for purpose was needed to describe the impact the agriculture sector has on warming.

“We need to be able to tell farmers, at this point in the future you will be climate neutral meaning you will not cause additional warming, and here are different pathways to get you there.”

Some rethinking needed

Mitloehner stressed the aim should be “climate neutrality”, not “carbon neutrality”.

He said, warming was the reason people cared about greenhouse gases, not because they produced carbon emissions.

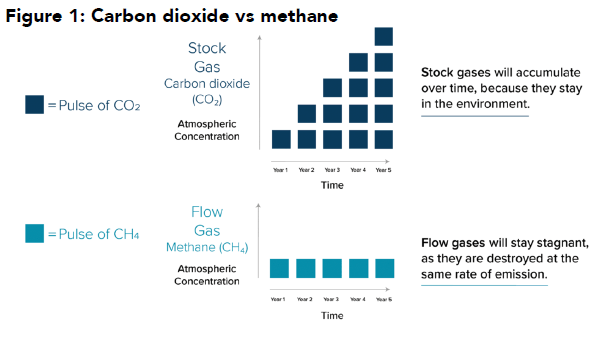

Mitloehner said the term carbon neutrality was often used in Australia and New Zealand. He said carbon neutrality was a useful term when burning fossil fuels. For example, in the transportation and power sectors, the main emission is CO2. For those CO2 emissions not to cause additional warming but to at least plateau, they needed to reach carbon neutrality.

However, in animal agriculture the main emission was methane, not CO2.

“That makes us a different beast, because it doesn’t mean we have to go to zero methane to stop warming,” he said.

Reductions of methane lead to reductions in warming. When methane reductions reach a point by which they no longer cause additional warming, that is climate neutrality.

For example, a constant livestock herd produces a constant amount of methane. Almost an equal amount of the methane that is produced by a constant herd is also naturally destroyed. This meant when there was a reduction of 0.3% methane a year, then it was not causing additional warming. Mitloehner said rather than climate neutrality, it would be better to reduce methane further and become part of a climate solution, which was preferable, because the fossil fuel side could never do this.

To bring about change he believed incentivising was essential.

“If you don’t enumerate reductions of a greenhouse gas like methane, it will not happen,” he said.

Mitloehner likened using incentives as a “carrot approach” and directive policies as a “stick approach”. He felt the carrot led to farmer buy in, and the development of innovative ideas, whereas the stick led to disconnect between farmers and what policy makers wanted to achieve.

Different countries’ approaches

Policy makers throughout the world have varying approaches to managing the impact livestock has on climate.

Mitloehner said the primary approaches he had seen were government investment to facilitate methane reductions, carbon trading schemes to incentivize methane reductions, taxation of methane emissions to encourage technology adoptions, and mandated reductions leading to herd reductions.

He felt one of the worst approaches was that taken by the Netherlands Government. It decided to reduce nitrogen emissions from the entire country, but rather than spread this over all sectors, including transport, it decided to make agriculture the only target for nitrogen reductions.

Mitloehner said the Dutch government invested 25 billion euros, and with this money aimed to buy 500-600 of the most-polluting farms and reduce the herd by 30%. A third of all farmers needed to stop farming dairy and swine. Farms are being sold under market conditions and farmers had to sign that neither they nor their children would ever be farmers again.

He said farmers were extremely upset, and there was a disconnect between the largest parts of animal agriculture versus what policy makers had in mind for them.

He felt this approach was unlikely to achieve what the policy makers wanted to achieve. Mitloehner didn’t support the Irish approach either. Policy makers there decided they needed to get rid of a third of their cows. Mitloehner said culling these cows would not reduce the demand for the products that these cows produced. Rather, this demand would be satisfied by another country, for example, Brazil or Germany, therefore moving emissions from one place to another in a process called leakage.

“Leakage is not reducing emissions, rather moving them from one place to another because demand is not affected,” he said.

The United States approach was to fund $2.8b to “Climate Smart Communities”. From this, $800m was going toward beef and dairy sustainability work. Mitloehner said the US government actively supported farmers to reduce emissions nationwide.

He said it was more than just incentives, with millions of dollars also going towards research.

Mitloehner said along with federal incentives there were also state incentives. To bring farmers on board, the legislation was written in a manner of financial incentives and partnership agreements between government and industry, which led to innovative ideas being implemented.

- First published in Country-Wide April 2023