A Canterbury equity partnership is making the most of bobby calves. By Anne Lee.

Maatua Hou means new parents and it couldn’t be a better name for the venture four young couples with young children have embarked on to grow equity and find a solution for another group of youngsters – bobby calves.

They’ve formed an equity partnership, bought a block of land and have found a group of dairy farms prepared to supply them with calves otherwise bound for the bobby truck, entering into a profit share arrangement.

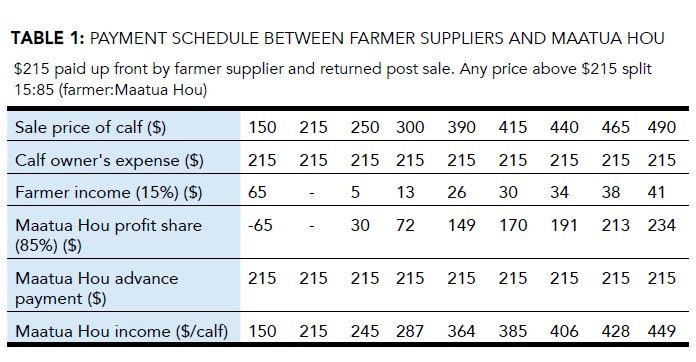

The farms supply four-day-old calves together with $215/calf, paying up front to partner with Maatua Hou.

Maatua Hou rears the calves to weaning at which point they’re sold.

Maatua Hou keeps the money from the sale, the farms are guaranteed to get their $215/calf back as a minimum once the sale has occurred and will share in any price over $215 at a split of 15% to them and 85% to Maatua Hou. (See table one.)

David Williams is Maatua Hou’s operations manager and the instigator of the idea that brought the young couples together in the equity partnership.

jail.

He’s worked for corporate farming entities as an analyst and last year became a self-described stay-at-home Dad while partner Phoebe Davies, a partner in law firm Wynn Williams, returned to work after the birth of their son Lachlan.

The pair and their equity partners shared their story at SIDE earlier this year.

About the time Phoebe returned to work David saw a property that ticked a lot of boxes when it came to land that could help them grow equity.

“I think there was just over a month from spotting the property on TradeMe, becoming a stay-at-home Dad, flicking texts out to people asking if they wanted to be involved in this plan – and did they have any money to put in – and then buying it,” David says.

The equity partnership and buying the land is at the core of the venture in that it’s brought the couples together, giving them a way to pool their resources and take on an investment none of them would have managed alone.

It’s also allowed them to pool their skills – which in this instance are diverse.

“We have real farmers, corporate managers, a lawyer, an accountant and a florist with the small business skills as well as farming skills.”

Ben and Jo Jagger contract milk 950 cows near Rangiora and both have a farming background.

“We were looking for opportunities outside of the farm job where we could invest.

“We wanted to be involved in an equity partnership and surround ourselves with like-minded people. It also came with the bobby calf business model.

“Humans are creatures of habit and don’t like change, but there are opportunities that come with change and that is exciting for us,” he says.

Brendan and Ella Kelly also joined the equity partnership.

They contract milk 1400 cows near Ashburton and also say the venture gives them the ability to invest contract milking returns into a land asset in a good location.

“It gave us a chance to get involved with a smaller scale equity partnership so we could learn some of the do’s and don’ts of running a business with a group of investors,” Brendan says.

“The other factor that appealed to us was a bit more of an emotive one in the business model and the alignment that had with our core values to make the system better,” he says.

The alignment of each party, their values and what they want out of the venture is important, David says.

“We’re all in the same stage of life and we want to use the equity partnership to grow our wealth – it’s definitely a growth strategy over the longer term.

“The aim as a group is for this to give us a greater ability to achieve future investments.

“We’re all gunning for herd ownership or land ownership and that could happen through this or it could be the staging post for other equity partnerships,” David says.

He’s the first to admit though that the first year of operation didn’t go as planned and honestly reveals that a range of issues meant the operational side of the venture made a loss.

The property ticked a lot of boxes: – it’s 34 hectares partially irrigated, it has calf rearing infrastructure and calf housing along with sheds; it has quality housing and is well located at Burnham near Christchurch which should lift in value as urban areas spread.

But – because they didn’t get take-over of the property till September 1, they had little time to get the farm set up.

Sealing a deal on the supply of calves took time so when calves arrived, they were already the later ones coming off farm and they arrived en masse.

David says he got a lot more No’s than Yes’s when he put the concept to multiple farmers to supply but in the end, he found farmers who saw the value in the venture from an ESG – environmental, social and governance – perspective and were happy to supply the animals and the upfront costs because of a genuine desire to give the calves a better outcome.

Getting a calf rearer at that late stage proved difficult and then to top it off they had a salmonella outbreak.

“Overall, death rates and milk powder costs were higher than budget, as we rallied to get on top of the disease setbacks because it significantly knocked growth rates. We learnt a lot in that process.

“We did get the earlier ones away and sold them for above budget, which was a positive because it showed us there was a market for broken-faced heifers and the type of calves we had.”

The irrigation restrictions and drought in Canterbury meant they had declining feed quality and quantity later in summer and coupled with a declining market meant they not only had higher costs they got squeezed on price too.

“So what did we learn? You can’t have a balance sheet strong enough.

“The business was set up with a conservative level of debt, which we thought was responsible given the higher risk model.

“Fortunately, we bought (the land) at a good time and demand for small farm blocks seems to have increased in the past 12 months, so this helps after a difficult first season, as we’ve likely had some uplift in land valuation.

“We’ve done a lot to prove the concept though in terms of a market for the calves and farmers to supply us.

“Straight out of the gate we’ve had a lot of first year blues but we’ve proven we can work together and a lot of the strengths we have in the group have shown through.”

Now in their second season the flow of calves has been a lot more manageable with an expected total of 750 calves reared.

They have one full-time staff member, Kim Knaggs and two part-time people, Julie Hazlehurst and Hayley Bykerk, who will step up their hours as Kim gets closer to having her first baby due in early November.

They’ve developed protocols for biosecurity to reduce the potential for disease given the number of farms calves are coming from.

They’ve set up “calfie jails” or quarantine pens in the corners of the large pens where any suspicious calves are put.

“Anything that looks a bit sleepy, hasn’t fed properly or we’re just not sure about goes in there so we can keep a really close eye on them.

“It gives the team a chance to watch them easily without having to find them in the group and it means they’re that little bit removed.

“It gives the team a chance to watch them easily without having to find them in the group and it means they’re that little bit removed.

“If anything develops they’re quickly taken away and go into the sick bay at the other shed away from any other calves.”

They have close contact with their vet and can communicate via WhatsApp to send videos and photos along with questions.

Part time staff member Hayley is studying to be a vet technician and works with the vet who comes once-a-week once numbers get up and disbudding is taking place.

The large pens and feeding regime means calves remain in the pens for about 50 days with the aim to hasten rumen development because they’re eating more grain than they would if out on grass.

That in turn should allow earlier weaning and reduce the amount of milk powder required.

The calves are fed two litres twice-a-day for the first 10 days and then go on to 3.5 litres once a day with that slowly increasing.

David works on 40-50kg of grain per calf till weaning.

“We’re working closely with the vet on our feeding plan and we’re monitoring calves really closely.”

Exercising the mind

David and the equity partners have been exercising their minds on the wider sector issue of bobby calves too.

The issue presents risks to the sector but it could also present numerous opportunities including increasing returns through marketing based on welfare and sustainability.

The big issue is finding the farmed area for the increase in beef numbers if large numbers of bobbies are reared.

One solution is to reduce the number of traditional beef cows and the subsequent calves carried on drystock farms, and have supply agreements to fill these properties with dairy-beef reared animals.

There would be greenhouse (GHG) benefits to such a move.

An option could also be for finishers to carry dairy cross animals through to 10-12 months rather than 22 months allowing more animals to be carried by the finishers and cope with the large number of animals that would be available if bobby calf numbers were significantly reduced.

“We have to apply some different thinking to the issue but it does start opening up exciting opportunities.”

- Maatua Hou. A bobby calf rearing venture with a twist – four young couples have set up an equity partnership, bought a 34ha block and created a venture where the farmers supplying the calves also pay. The farmers a guaranteed to get their money back when the calf is sold along with a share in any profit. Could this be a way to help reduce bobbies? Is there another way we could be rearing beef in this country? Take a look at our story:

- www.youtube.com/watch?v=yLxdY5mkH8Y