Our shrinking pool of people

New Zealand’s workforce is shrinking - and there’s no way that will change, a leading economists says. Anne Lee reports.

If you think there was a staff shortage over the Covid period – you ain’t seen nothing yet, economist Shamubeel Eaqub warns.

If you think there was a staff shortage over the Covid period – you ain’t seen nothing yet, economist Shamubeel Eaqub warns.

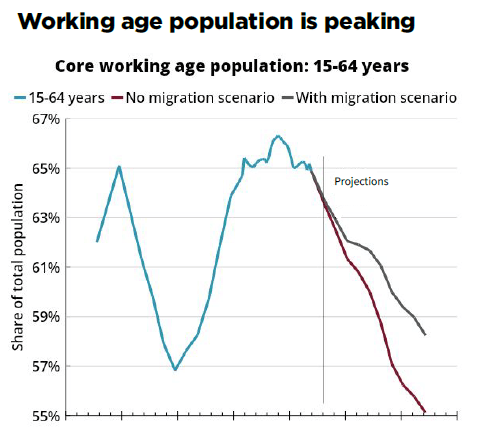

Based on New Zealand’s population dynamics this is the last year NZ will have more people entering the workforce than retiring.

“Our labour pool is shrinking and that won’t be made up by immigration.

“There is no scenario in New Zealand’s future where we have enough immigration to offset the aging population,” he says.

Labour issues aren’t just issues of today, they are the issues of the next 20-40 years.

Farmers shouldn’t be worried about the future demand for their product.

“The demand for food will remain extraordinarily strong so there will always be an ability for us to sell the product – that’s not the point.

“I would be more worried about whether we can produce it.”

In the short term, the global economy is slowing and the domestic economy is no different.

The stimulus from governments and central banks pumped up money supplies as a response to Covid but it created excess demand and prices have risen.

Now the brakes are on – interest rates are being pushed up and governments are cutting back on spending.

“We haven’t had inflation like this since the 1980s and it’s synchronised, all around the globe.”

Consumers and business owners are all saying the same thing – they’re worried. Confidence in the economy is low and people are being cautious.

“That affects every part of the economy – making decisions to buy, to move job, to hire someone. Everything takes longer.”

On the flip side, it’s a great time for people with cash.

“I’m not sold that inflation is here for a long time because there’s so much debt in the world economy.

“Interest rates are really hurting people and there’s going to be a lot of pain in the next 12 months.”

The inflation we’ve seen in NZ is cost-driven and the United States issues the global media is “obsessed with” in his opinion don’t ring true here.

He does not see a wage/price spiral and says real wages have not kept pace with cost of living increases. “The positive is we are starting from the best possible position.

“We started this recession with the biggest share of the population in jobs we’ve ever had. No other OECD country had a bigger share than us.”

But as a country NZ is also at the peak when it comes to the percentage of the population aged between 15 and 64.

“It’s so obvious and so predictable. The pool of people who are going to be our workers is shrinking.

“It means we’re going to have to do things a lot smarter.

“What I want you take away here is the sense of urgency about this.”

Opening our borders to immigrant labour is not going to solve the issue.

Every other country is opening their borders and many offer far better pay relative to living costs than we do, making NZ less attractive to would-be migrants, he says.

Added to that, young New Zealanders, part of the Kiwi working population, are leaving to seek out those offshore, well-paid opportunities too.

“The subtext to the Government’s immigration settings make it clear we don’t really want migrant labour.”

It’s folly to rely on immigration because the public policy settings change with each incoming government or even within electoral cycles.

While public policy on issues such as immigration should be set based on data and evidence rather than ideology, the fact is politicians make policy based on polls, he says.

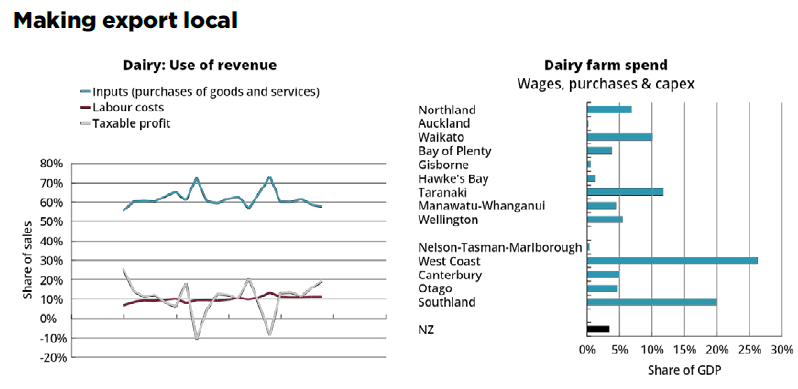

The dairy farming sector in NZ has reached a level of maturity, with the recent years of rapid growth now behind it.

“Maturity comes with responsibility.

“When you’re in a state of maturity it’s about doing your business better.”

It’s important to think strategically, understand what you’re doing and why you are doing it. The dairy sector has always had a strong focus on efficiency with 1.5% efficiency gains year on year for 20 years.

No other sector has been able to do that, he says.

“But that story hasn’t been told well.

“The fact we have amazing scientists and producers, innovators and productivity deliveries that provide the returns they do to the New Zealand economy – that story has to be told better.”

To have the social licence to operate – and be “able to” produce the food that global markets will have an increasing demand for – the language around dairying’s contribution to the economy needs to change.

“We have to take that language away from the national numbers because when we talk about billions of dollars no one really knows what that means – it loses its relevance.

What’s more important to communities is the contribution the sector makes to them.

“It’s the 60% of your revenue that’s spent in the region – the contractors, the service companies, the impact that spending is having.

“Until you can translate the big numbers to what it means for your community, it’s very hard to gain social licence.

“We need to tell our story in a way that matters to those who are listening, not what matters to us as farmers.

“You are not the audience.”

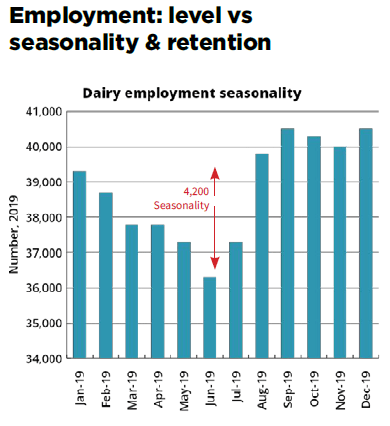

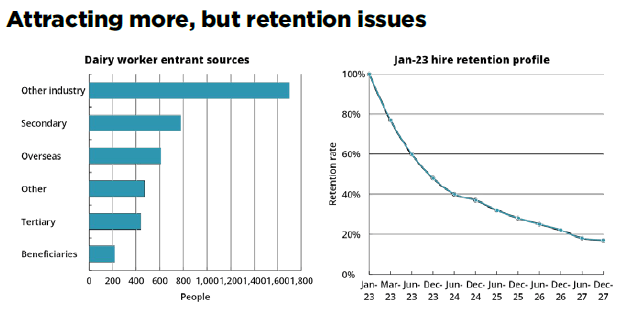

The labour issues facing dairy aren’t due to growth in the sector anymore.

“It’s more about the way we churn and burn our people.”

About 40,000 people are employed in the dairy farming sector with about 4000 coming and going annually.

“So, it’s not about bringing more people in. It’s about dealing with the churn and keeping the people we have.

“We’re not keeping our people stable, and secure and loyal.”

In a year, 40% of the people taken on today will still be in the sector but in two to three years very few will remain.

One way to keep people is to give them specialised training, he says.

Give them career progression and give them career credentials through training.

“Invest in your people.”

People who are highly specialised in a particular sector are more likely to stay in that sector because they can earn better money there than in other areas where they have few credentials.

Most dairy staff come into the sector with few qualifications past high school.

“But the biggest shortage of people we’re going to see in the labour market over the next 40-50 years is people with no post school qualifications.”

The dairy sector pays better than other primary sectors but that alone isn’t enough to keep people.

“What do workers want?

“They want money.

“They want security.

“They want flexibility.

“They want work-life balance.

“They want fulfilment.

“Why would they want to work for you when someone else is going to give them the same money for a job that’s less hard.

“If they’re miserable they are going to leave and take a job that’s less work, closer to stuff and not so isolated.

“We can’t keep saying this is the job and this is the way we have to do it.”

Too often the leadership teams in farming businesses spend too much time working in the business and not enough time thinking strategically about things like how to make changes to job requirements.

“So, what can you do? “Is there another way to split the role, is there another way of doing a particular job?

“I hear this time and time again – we don’t have time to think about the strategy and plans.

“We have no time because you’re too busy working in the business and not on it so we lose sight of the opportunities to improve it.

“Invest in the management capability of your leaders – that’s a key to retention.”

That could also mean investing in your own leadership skills.

“These are significant businesses. You’re not a farmer, you’re a leader – a leader who happens to farm.”

Shamubeel urged farmers to be more flexible in their own thinking so they could meet the flexibility requirements of the workforce.

“We underuse 50% of the labour resource right in front of us – hire more women and give them the flexibility they want.”

That may mean re-arranging jobs to create different hours or rosters.

“Attract older people – they can be great for pastoral care but think about the work, again be flexible.”

“Invest in training and career progression.

“You may need to ramp up overseas recruitment but don’t rely on it solving all of your issues.

“Invest in long-term labour force planning with industry and government.

“You are going to have to think differently and you’re going to have to start now.”