Paddock to plate productivity

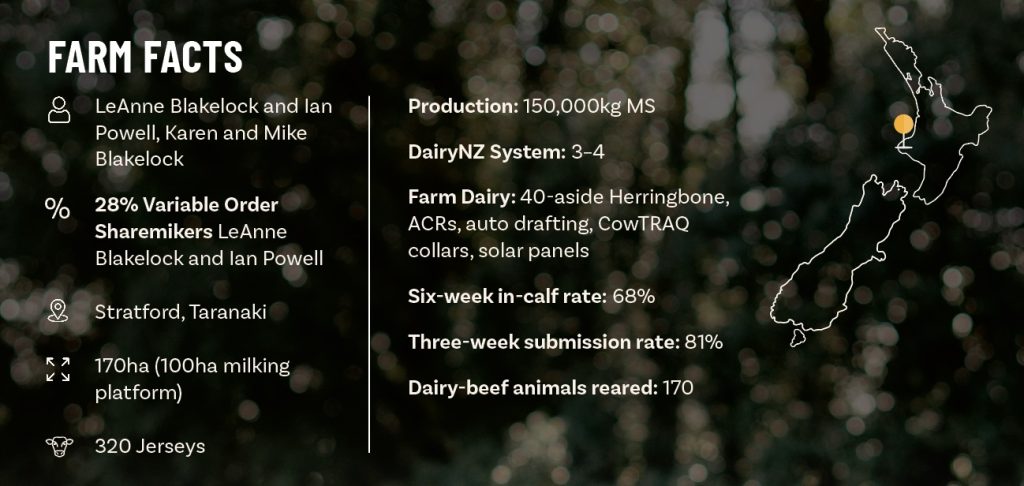

Taranaki dairy farmer LeAnne Blakelock has launched a Rose Gold Veal brand in an attempt to reduce bobby calves and connect her dairy business closer to the beef value chain. Words Sheryl Haitana, Photos Natalie Waugh.

For the last few years, LeAnne Blakelock and her husband Ian Powell have reared 80% non-replacement calves born on farm to increase their business productivity while raising the value of their Jersey

dairy beef.

LeAnne began experimenting with rose veal a few years ago and is now working with local Taranaki farmer and meat processor Shane McDonald to launch her own Rose Gold Veal brand.

“We’ve always reared a few rose veal calves on farm for our freezer,” she says. “Essentially, you keep feeding a spring-born bobby calf milk through the season, and process it in February. It’s just a little bit different than your usual beef.”

The animals are reared to 300kg liveweight by 26 weeks, with a processed carcase of around 145kg.

Shane started café Field to Fork in New Plymouth and is selling products in the shop and online via his micro abattoir ‘Meat to You’, showcasing meat that is grown and processed locally.

The vision stemmed from Shane and his partner Kylie breeding their own top-quality stock and feeling frustrated by the limited opportunities to take their product directly to the consumer.

“We know that New Zealand farmers are amongst the best in the world and we are proud to support and showcase farmers in our local communities through the Taranaki Prime brand,” says Shane. “We are also well aware that farmers in general want to be part of a bigger story and have a connection with the consumer.”

“This isn’t just about calves or carcases. It’s about community and about people.” – LeAnne Blakelock, Taranaki

The business is expanding, bringing more local farmers on as capacity allows.

“My relationship with Shane isn’t just transactional,” LeAnne says. “We talk for hours, we align on values. That’s what makes it work. It’s more than animals and invoices. A lot of farmers reading this would feel the same – they have a connection to their animals, and they would like to see the value of that meat on a plate.”

LeAnne also rears about 30–40 Wagyu calves for First Light on an eight-month contract, paid on kilo of liveweight, and sells her other dairy-beef calves direct to buyers. She believes the dairy-beef sector needs a deeper rethink, particularly around collaboration and contracts.

“I really believe in contracted dairy beef. I think it’s good for the industry. It gives us a guaranteed outlet and being paid by liveweight means we are rewarded for doing a good job.”

New Zealand has two opposing industries – dairy and beef – that want different things from a calf born.

“We’re sending calves through beef supply chains where no one knows their sire, their health history, or how they were reared. It’s madness.

“I advertise my weaned beef calves with everything listed – traceability, health, vaccinations, genetics. Buyers love that. It’s what I’d want to know if I was buying.”

Ideally, beef finishers would pay more for an animal they know has had a better start, and has superior genetics to grow.

Improving productivity

Their journey to rearing more calves on farm and finding superior outlets for them started from LeAnne’s knowledge as an accountant. She was looking at New Zealand’s decline in productivity and reflected on how she could turn the dial in her own business.

“I asked how we could increase the productivity of the animals that were being born on farm. Our calves born were being purely judged on what they looked like.”

The beef industry is so reactive, with no reward for meat quality, which needs to change, she believes.

“I’ve got Jersey-cross beef animals, which typically are the poor cousins of the beef world.” But their meat quality is superior and the Jersey animal works better in a lot of dairy systems; it’s smaller on hill country, she says.

When looking at the productivity gain, LeAnne thought veal was the obvious choice to have a play with.

“We’ve been killing a few for home kill for a few years; last year was the first time our calves were processed by Shane and sold into retail.”

The obvious issue for scale of the veal product is processing space, she says.

“Shane has essentially unlocked and created that solution, which is amazing. We had a soft launch and put four animals through his café and sold them to a few local butchers and some restaurants. The feedback has all been really positive. But I want the constructive feedback as well.”

“I advertise my weaned beef calves with everything listed – traceability, health, vaccinations, genetics. Buyers love that. It’s what I’d want to know if I was buying.” – LeAnne Blakelock, Taranaki

This year, LeAnne has 20 Jersey-Friesian cross calves that she has earmarked for the veal market.

She attended the Dairy Calf & Heifer Association Annual Conference and Trade Show in Colorado in April, which also covered the topic of veal processing.

“The United States uses a lot of things like steroids, hormones, plasma, which we obviously don’t use, but it’s fascinating. If you look at the US they’re only doing 400,000 veal animals annually and we’ve got about 2 million bobby calves to deal with. So veal is not the golden solution for all bobby calves, but it could be part of it. It fits within the existing rearing space for farmers.”

Driving genetic gain

The first step to building productivity for their non-replacement calves was to focus on the beef genetics they were using, because it’s not about getting a bigger calf born, says LeeAnne.

She has been working closely with Ben Watson from GENEZ and running trials on farm using various sires. Last season, with Ben’s guidance, they trialled various genetics for different breeds including Belgian Blue, Wagyu, Simmental, Angus and Charolais and were impressed with the improvement in growth from selecting particular sires.

There’s a lot of discussion around low birthweight and easy calving versus a large calf that attracts more money in the feeder calf sale pen. But ideally, LeAnne is aiming for a medium-weight calf that then has the curve-bending genetic potential to gain that weight outside of the cow.

“My frustration is always that I can put forward our calves at the sales, I’ll get more money for the big ones. But I know that my medium ones, because I’ve tracked them for years, actually perform better.”

The fact people are typically buying on their eye without any knowledge of the bulls used or their growth potential is madness, she says.

“You’ve got the big meat companies talking about provenance stories and traceability, but that’s not what I am seeing on the ground through the sale yards.

“So veal is not the golden solution for all bobby calves, but it could be part of it. It fits within the existing rearing space for farmers.” – LeAnne Blakelock, Taranaki

“The only way to make money in the beef industry is to almost rip somebody else off; you get a good price for something because someone else likely overpaid for it. For the sales, it depends who turns up on the day, trends, everything like that. I think we need to be able to do this better.”

LeAnne and Ian use sexed dairy semen over their herd for three weeks. They typically get 50% conception for sexed semen, but with an 81% three-week submission rate, they are getting enough replacements out of their Jersey cows in that period.

“We have had a bit of a hit to our conception rates, but I really believe the earlier-born calves do a lot better, regardless of genetic potential.”

They then switch to all-beef genetics using artificial insemination (AI).

“Our last mating results weren’t fantastic. We had a few metabolic issues during a very wet spring last year and some staffing issues, so it was a bit of a rescue mission heading into mating.”

Feeding more milk for cell multiplication

Once they had tackled genetics, the next focus was on epigenetics, the environmental influences on genetic expression.

“So essentially, how you rear and feed an animal and what that does to its genetic potential.”

LeAnne is focused on an accelerated calf growth system that focuses on nutrition and immunity from day zero.

“So many people think accelerated growth means pouring grain in later on. But for me, it starts with colostrum and early immunity – those first four weeks are critical. And that’s where my neonatal calf stuff comes into it, and where I really found my niche, because the general overarching philosophy in New Zealand around economical calf rearing is stacked, in my view, incorrectly – we’re not feeding our calves enough milk, usually in the first four weeks, and therefore stunting their ability to really grow in later life.”

A calf’s growth is all about cell multiplication. So more food equals more cells; more liver cells, more heart cells, more immune cells, more bone cells. In a future dairy cow, it’s more mammary cells, she says.

“For the first four weeks, all a calf can digest is milk, and it seemed mad to me that we were holding them up nutritionally and then expecting them to grow. After that four weeks, cell growth switches from multiplication, to the actual cell itself getting bigger. So I set about looking at how we were feeding them to get the most cells, so that they can then go out and grow better.”

All calves get ad-lib milk, drinking up to 10–11 litres a day, and are weaned between 8–9 weeks once they’ve doubled their birthweight.

We do feed a relatively high milk system. I won’t shy away from that.”

In that system, the calves gain an average of 1kg/day for the first four weeks, which drops to about 0.8kg/day when they wind the milk down, before going up again. Calves are weighed on day one, and then weighed fortnightly.

“We look at the trajectory of what weight they were born, and the consistency of their growth.

Weighing them regularly, we can spot a problem earlier and can drop them back to a younger mob if they’re not gaining enough weight.”

It’s about monitoring and managing the calves as individuals. There are 100 things you could do to influence calf rearing; it’s about addressing each thing one at a time, she says.

The aim is to have well-grown, high-immunity animals that then carry on a high-growth trajectory out through to finishing.

Her challenge has been to increase the meat yield by 5% without adding any more inputs.

Another big focus for LeAnne is minimising any stress on her calves. That doesn’t mean the flashest infrastructure, but simple things like no exposure to drafts, dry bedding and access to clean fresh water make all the difference.

“Happy, low-stress calves will grow better. If you’re pouring all this beautiful energy into calves that are cold and stressed, half that energy is going into keeping warm; you’re just wasting your money. I think there are massive productivity gains to be made just through improved systems.”

This feeding approach has also dramatically reduced mortality on farm.

“Out of 250 calves last year, I lost five, and those were for ridiculous reasons. Not from things that should be preventable.”

Sharing the stress realities

LeAnne wears many hats: accountant; dairy farmer; neo-calf expert; and mental health advocate. When she first started rearing calves she was not experienced, and she didn’t cope well with the calf mortality and the isolation of the job.

“I came into calf rearing as an accountant, with ponies and a lifestyle block background. And every year, calves kept dying, no matter what I did. It was the most emotionally distressing thing I’ve ever done.”

That struggle and the silence around it drove her into mental health advocacy. LeAnne has volunteered for more than a decade working with suicide prevention initiatives like the Taranaki Retreat and Community Center Waimanako. She runs a Calf Chronicles Facebook page to share her knowledge and be honest about the wins and the failures, and talks to groups like Dairy Women’s Network about the realities.

“It’s not all beer and skittles. There are spectacular f***-ups. But I want people to see that and learn. It’s about continuous improvement, not perfection.

“We’re not feeding our calves enough milk, usually in the first four weeks, and therefore stunting their ability to really grow in later life.” – LeAnne Blakelock, Taranaki

“I sucked at calf rearing. I stand up and say that. And this is me making peace with all those calves that died when I didn’t know better. But I’m still here. And I’m doing something about it.

“There is so much shame in calf rearing. So many, especially women, feel like they’re failing, dragging around babies and buckets, wrecking their bodies, trying to keep everything together. And we don’t talk about it.”

With rising innovation, better genetics, and farmers increasingly looking for meaningful solutions, LeAnne is hopeful for the dairy and beef industry to work together to find the answer.

“This isn’t just about calves or carcases. It’s about community and about people.”