Paradise by the awa

After buying their own piece of paradise first farm Blair and Penelope Drysdale have thrown themselves into welcoming the community in to help restore the mauri (life force) of the awa running through the farm, the Manawatu River. By Jackie Harrigan. Photos by Brad Hanson.

After 16 years working in the dairy industry, Blair and Penelope Drysdale achieved their long held dream and bought their first farm five years ago.

Now, realising what a special place they have in Te Miro farm and relishing the ability to do whatever they like on their farm, they have thrown open the gates and welcomed in the local community of Norsewood, and the greater Tararua region, at the headwaters of the long and meandering Manawatu River.

Further down the river, it held the reputation for being one of the most polluted in the country and while that is now being remedied, the state of the awa even at the top of the catchme nt was much reduced from when the first Norse people settled the area 150 years ago.

Penelope and Blair fenced off 18 hectares of weedy, degraded river margin and began planting shortly after they arrived and have been helped on their journey by local iwi groups, the Norsewood school and many members of the community. (Read more, pg 58).

Catching all the weather, making improvements

The 146ha (132ha effective) rolling to steep, and challenging dairy farm is tucked up under the Ruahine Ranges and catches all the weather, Penelope says.

“It’s a very unique environment – can be the windiest, the wettest or the driest…we don’t do conventional weather. “

“It’s a very unique environment – can be the windiest, the wettest or the driest…we don’t do conventional weather. “

The proximity to the Ruahine ranges and the rolling terrain makes the 13-years-converted farm a marginal dairy block – and while the Drysdales say they have always been attracted to interesting farms, because it is a challenging farm they don’t think it feels right to farm it conventionally.

“We really are at risk of losing soil to wind and water erosion and so need to farm conservatively to make us resilient.”

Blair grew up in Nireha, out of Eketahuna and Penelope hails from a Pahiatua sheep and beef farm.

Blair had 16 years on a mix of high intensity to low input systems after travelling and working harvesting and farming in the United Kingdom and Australia. After three years lower order and seven years 50/50 in the Wairarapa and Tararua, they were ready and very keen for ownership and, having been beaten to many farms by drystock farmers who were buying rundown dairy farms to decommission them, the couple knew the Norsewood farm was perfect for them – and they were successful in buying it.

“That was easily our biggest life achievement – it was epic.”

Much keener on sheep farming, Penelope had worked for biological fertiliser company Outgro for many years and was a biological farming convert, and the couple farmed under that system on their last sharemilking job and brought the system and a wealth of nutrient knowledge to the Norsewood farm which had rundown soils but great infrastructure.

“This farm has had heaps of artificial nitrogen applied and has high P retention, and we were brave enough and had the knowledge to replace the N with heaps of fine lime slurries and transitioned to a more regen type of regime – and it has happened beautifully,” Penelope says.

Their first five years have not been without their challenges however, as the stress of high debt and two droughts followed by massive flights of grass grub have made life interesting, with a farm building fire thrown in, taking out all their winter hay supplies.

Undefeated they have rolled with the punches and have worked hard, fencing off 20km of waterways, including the Manawatu river stream, planting 40,000 trees and riparian plantings (over five years) and incorporating a 60ha runoff into the platform leased from Penelope’s parents, allowing them to be self-contained and run all stock onfarm.

Fully OAD milking, they have also been transitioning to organic over the past two years and have one year to go for full organic status.

The farm is unconsented under Horizons One Plan, although Penelope says she has tried to get the consent numerous times.

Moving away from reliance on chemical fertilisers, Penelope says they have found a system that works on their farm, but regen is a very individual system.

“What works for you may not work for your neighbour,” she explains. “We haven’t gone too deeply into massively high covers and constant shifting and trampling – we are learning as we go.

“If you are not winning, you are learning – and we do a lot of learning,” Penelope says.

In the past Blair has farmed intensively and within high-input systems, before moving to a less-intensive middle-input operation and then OAD and lowest intensity, and he says he is amazed at how much money has fallen out of the bottom of their current system.

“Every system you can do well, but for us, this is the best system to do well in.”

Proactive, not reactive

The couple say farming the regen and organic system means they have to keep their finger on the pulse and be very proactive.

“You don’t have any quick fixes in your pocket – you have to have the little glass ball out and be figuring out what is going to happen – you could drive yourself broke quite quickly if you aren’t being proactive – reactivity is not a word you can use with organics.”

They are not afraid of trying new things though, explaining how they have carted 400 tonnes of compost from Hawke’s Bay to fertilise their maize and summer crop of mixed forages.

The crop is actually a mixed sward, with 17 species of forage and herbs that will be oversown after three summer grazings with a mix of pasture grasses.

Building the herd

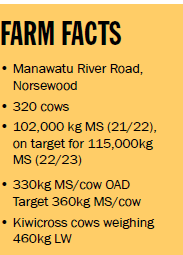

The Drysdales are running 320 cows this season, and plan for 340 cows next season while they have an extra block of local lease land.

“We are running some extra just to try to get our debt down a bit.”

The majority of cows are spring-calving, but Blair bought in 50 in-milk cows last autumn to milk through the winter and mated them with 28 to calve this autumn.

“Winter milking is not easy but while we have the extra land we plan to cash in on our milk qualifying for organic EU status and our payout jumping by an extra 60cents/kg milksolids (MS).

“Pumping up the autumn production bumps up our autumn income but winter milking is not going to be standard for us.”

With 320 cows they have produced 102,000kg MS last season, but are targeting 115,000kg this season and are currently 8000kg MS (13%) ahead.

The cows crashed on moving to Norsewood’s volcanic soils but now the Drysdales are happy they have them back on track and heading for 340-350kg MS/cow/year.

The biggest benefit of the OAD regime is the way the cows rebreed – after 9.5-10 weeks of mating the not-in-calf rate has been between 4-7% since going OAD seven years ago.

“Calving terrifies me every year because it’s basically over within a four week period – it’s chaos,” Penelope says.

“Thats OAD – the biggest benefit of OAD is getting the cows back in calf – I worked out this year I calved 88% of the cows in four weeks starting August 10 and we had 7% empty last year and 4% the year before,” Blair agrees.

They only need to rear 65 replacement heifers and so 3.5 weeks A.I. sorts that and 100 beefies (Hereford and Speckle Park), and then the Jersey bulls go in, Penelope says.

Blair’s mantra is “OAD is not about production, it’s about reproduction.”

‘We love bobby calves’

It’s not a common view, but Blair and Penelope celebrate the place of their Jersey cross bobby calves in the industry saying they are not worth rearing and are made into valuable byproducts.

“We do the best by them while they are onfarm, but to keep the system simple, off they go,” Penelope says.

“No one talks about the boy chickens going into the bloody mincer – but we are made to feel guilty about bobby calves going on the truck.

“If that is the only waste going out of our system then we are doing pretty well – and they are not actually waste – they are made into high value products – unlike all the fruit wasted on the ground under the apple trees.

“I sleep well at night – and I love when that bobby calf truck comes,” Penelope adds.

“It would be really inefficient if we had to rear bobby calves as well – we are looking after all our animals really well – but our system would be put under great pressure if we had to rear them too,” Blair says.

“It’s also protecting my cows and my heifers by not using beef bulls over all of them to try and get a beef cross calf out of every cow on the farm.”

Their 70 other non-replacement Hereford and Speckle Park beef cross calves are sold to a local rearer at four days old.

Thriving ecosystem farm vision

Blair and Penelope have a farm vision, to regenerate a biodiversity-rich thriving ecosystem.

What began as a project for them to protect and plant their farm for biodiversity and animal shelter has grown into a massive community effort and brought great benefits for both their family and the local community.

After imported riparian plants struggled to thrive the couple decided to ecosource their own seed and turned the remnants of the woolshed they lost in a fire (that also incinerated 300 bales of hay) into a ‘wananga nursery’.

With a target of propagating 20,000 plants each year, the local Norsewood school children and helpers have potting days and planting days – the children have learnt the skills and helped to grow 12,000 plants this year which Penelope says really embeds their learning. With funding from the Manawatu River Leaders Accord, Horizons, Fonterra and a hefty input from Te Miro farm, plants propagated from the nursery will be split 50% for farm planting, 25% for further down the river and 25% to be sold for school funds.

“The community planting days have blended the river project with the farm planting and it’s really special to collaborate and to be able to create relationships and partnerships,” Penelope says.

The Manawatu river on the eastern side of the range has a name that means ‘dark meandering river’ and the couple have plans for the river and road frontage to create access for the community and also to grow a canopy over the river that cools the water and encourages stream health.

“People ask us what we do all day since we are only milking once a day – but we have planted 40,000 trees on this farm – it’s pretty addictive once you start to see the progress,” Blair says.

“The other locals have really struggled through the tough spring, but being OAD our cows have rocketed ahead – it just shows that with the organics we need to be more resilient and OAD helps that.”