A Takaka Valley farm is consistently at the top of the region’s operations for profitability, Anne Hardie writes.

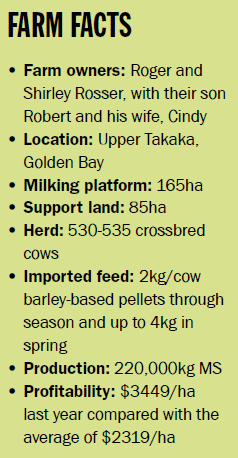

For the past five years, Rosser Holdings in Golden Bay has consistently been one of the most profitable dairy farms in the Top of the South’s DairyBase data, reaching $3449/hectare last year compared with the average of $2319/ha.

On a cold July day, the Rossers were one of two farms in the bay to open their gates for a field day to explain how they balanced production and costs to lift profit for their business which is owned and managed by Roger and Shirley Rosser, with their son Robert and his wife, Cindy.

The business near the top of the Takaka Valley encompasses a 165ha milking platform and an adjoining 85ha support block where the cows winter for six weeks. Between 530 and 535 cows are milked through the season which is close to 3.1 stock units per hectare. The herd consistently produces about 220,000kg milksolids (MS) through efficient grass utilisation and also up to 380 tonnes of pellets fed in the dairy.

The most recent data was evaluated from the 2020-21 season which showed the Rosser family produced an operating profit of $2.56/kg MS compared with the benchmark of $2.29/kgMS to give an operating profit margin of 31.4% compared with the benchmark of 28.9%. Operating expenses for that season on the farm was $5.59/kg MS compared with the benchmark of $5.63/kg MS.

During that season, the farm harvested 12.4t DM/ha compared with the benchmark of 11.1t DM/ha and pasture made up 76% of the cows’ diet.

The barley-based pellets have been a consistent addition to the cows’ diet on the Rossers’ farm and despite the cost of the imported feed, it is part of the equation to successfully achieve high profit. The cost keeps going up though and Robert acknowledges the sight of a truckload of pellets showing up at the farm scares him sometimes because he knows how much that truckload costs.

Freight alone costs $117/t for the truckload so he reckons you might as well buy a good pellet. That said, the price for pellets has risen by 30% in the past year to $670/t which makes budgeting difficult. If more Canterbury farmers switch from palm kernel to barley, he expects the price to continue to rise. But he likes the barley pellets and they have worked well for cow nutrition as well as cow flow.

“Pellets are lollies. We had to put rubber mats down because they want to get in there. Some cows will back off and try to jump on again – they get quite cunning.”

He starts feeding high-energy pellets to the springers from July 20 and keeps feeding them through to the end of mating, when the rocket-fuel variety are swapped for a cheaper, basic pellet for the rest of the season. The herd gets 2kg/cow of the pellets daily for most of the season and can be fed up to 4kg a day in September to get the cows humming. Every year the cows are fed the same amount regardless of the milk payout.

Minerals are fed separately through a dosatron dispenser, using a mix that was made up by the Rural Service Centre years ago. This is about to change though, with a mineral pellet feeding system being installed in the dairy to replace the dosatron system. Robert says that will guarantee each animal receives the correct dose of minerals daily as dosatron does not serve every paddock and cow intake can vary.

Pellets are fed in the 50-bail rotary dairy which is part of the higher capital costs on the farm, including pivot irrigation and machinery, but also one of the reasons the farm can run more efficiently.

Two staff members work alongside Robert on the farm and the dairy is a one-person operation at milking. That frees up time for one of the employees to do other jobs around the farm instead of helping with milking. During spring, employees get to sleep in twice a week because they aren’t both needed in the dairy. Anyway, Robert likes morning milkings.

“I like milking cows in the morning because no-one annoys me and I get a good look at the cows.”

Money is spent on machinery for mowing, balage and spraying, but Robert says it enables them to make big savings by being able to carry out those jobs themselves. Plus, it makes good use of the staff they employ. Keeping up with repairs and maintenance is a key aspect of the business.

“I try to buy new gear all the time because I hate old gear breaking down.”

Most years they try to make balage and will take a paddock out of the round for three to four weeks to make quality balage straight out of the round, then have it back in the 24-day round they follow throughout the season. Balage and hay are also made on the neighbouring support block which means it is not far to carry it to the milking platform where balage is fed through summer and also autumn to slow the round down. Light balage gets chopped so the cows eat it better and they will often get a second or even third cut off a paddock.

Having their own equipment means they can get good use out of nitrogen in the form of N-Protect by spreading it behind the cows at 50kg/ha when the weather allows through spring and that keeps the grass growing for the higher stocking rate. On the irrigated land they apply 160-170kg/ha/year and on the unirrigated paddocks about 100kgs/ha.

The three pivots are part of the high capital costs for the farm, but integral to keeping pasture growing through dry summers on river flats and terraces. Soils over three terraces go from gravel to silts to pakihi on the hill block and the bottom part of the farm is 30% more productive than the hills. Adding irrigation to the productive soils keeps the grass ticking along nicely.

Water consents from the Takaka River don’t guarantee water though. It depends on whether or not the Cobb Power Station is generating power. When it is really dry, the water can be turned off two to three times a day which means it is not possible to run three pivots at once. When westerly winds whip down the valley, the pivots can struggle to keep up with the loss of moisture from the soil. The pivots cover 70ha, with another 40ha irrigated via K-line. A TracMap unit on the bike has made it easier to move the K-line irrigation and Robert says they are growing more grass in those areas now.

Cows are split into two herds for the entire season, with mature cows milked twice a day on the irrigated pasture and the younger cows milked once a day from Christmas on the unirrigated land. The latter have the furthest to walk to the dairy and get topped up with balage when it gets dry, plus pellets in the shed.

No summer crops are grown and likewise no winter crops. Running a higher stocking rate makes it difficult to take too many paddocks out of the system for resowing and an alternative is undersowing damaged paddocks to top up pasture. When they do regrass a paddock, they spray it out and sow it themselves which means they have flexibility to get it done when they want.

Some of the pastures are 20 years old and Robert says lack of longevity is one of the problems with many of the newer pasture species. The older pastures can get a bit clumpy though and need to be topped regularly through the season to control quality. Key to the business is keeping everything simple and staying consistent with fertiliser, feed and cow numbers to ensure the success of the following season. Part of keeping it simple is a laid back approach to mating. After years of breeding the original Ayrshire herd toward crossbred using both Friesian and Jersey genetics, the farm now uses crossbred straws for mating and only uses artificial insemination (AI) for three weeks, with the bulls put with heifers the same day they begin AI.

“The technician turns up and whatever cow is on the platform gets a straw. Easy, simple.”

Six-week in-calf rates and submission rates are only slightly above average and mating continues for 9.5 weeks. But for the past three seasons the empty rate has been between eight and nine percent, without cidrs, vet checks or basically anything and the goal is to continue to keep it under 10%. The lower empty rate ensures they get about 110 replacements each year and hence there is no need for sexed semen. Instead, they have heifers to sell. Cows have longevity in the herd and Robert is quite serious when he says they try not to keep cows beyond 11 or 12 years old. Calving kicks off from August 5 these days because irrigation gives them the ability to grow more grass through summer and didn’t have to rely on more days in milk to compensate for the dry. The breeding value (BW) for the herd is 137 and production value (PW) 187, with Robert conceding some cows dip into negative values, but that is no concern to him. As long as a cow is proving herself with milk into the vat, he is happy. On average, cows produce about 410kg MS to 420kg MS.

Though the business is production-focused, with higher stocking rate utilising the pasture they can produce, Robert says they don’t chase production and that’s another reason for keeping the system consistent. The focus now is on tweaking some areas such as grass management to produce a bit more milk and shopping around for products to cut costs where possible.

Hanging over the farm and several others in the area is the Te Waikoropupu Springs water conservation order that recently went to the Environment Court. The issue has been around the source of nitrates in the springs and whether they are natural or due to human activity.

COST CONTROL CRITICAL

Five years of data in the Top of the South shows it doesn’t matter whether farms have a low or high-input system to achieve high profit, but rather the ability to control costs.

Nearly 40 farms in the Tasman and Marlborough region now provide data for DairyNZ’s DairyBase and 28 of those for at least three years.

Profitability varied on farms over the years, though top-profit farms consistently ranked in the top five farms and proved that every system can be profitable, whether it is system 2 or system 5.

In line with national data, the data confirmed a strong and consistent relationship between the amount of pasture and crop eaten per hectare and operating profit per hectare. Though there was no relationship between purchased nitrogen and profit.