Words by: Phil Poulton

Recent research into the management of downer cows was conducted on dairy farms in South Gippsland, Australia, during the winter calving periods of 2011 and 2012 in conditions similar to typical dairy areas in New Zealand.

The results showed that secondary damage was often more important in determining the cows’ eventual fate than the original cause of the recumbency, and the quality of nursing quality was a key factor in their chances of survival.

When a farmer first finds a down cow it is important that the cause is determined to ensure correct treatment.

Veterinary assistance with that may be needed. A plan needs to be devised to ensure the cow is correctly treated and managed.

A ‘non-alert’ down cow is an emergency and should be dealt with immediately. ‘Alert’ down cows can be dealt with as soon as possible unless they are in a position that could cause harm to themselves or other animals, such as lying on their side, having their head downhill, or being exposed to harsh weather.

If a cow is suffering unduly she must be promptly and humanely euthanised. This is important because consumers demand high standards of animal welfare on farms. Down cows that haven’t recovered after a few days and can’t be nursed intensively, and cows that are unlikely to recover,should also be euthanised.

Treatment:

Drugs, if needed, must be given in the appropriate time to maximise the chances of a quick recovery. If the cow is not responding as expected, a re-assessment is required to ensure the primary diagnosis was correct and to consider secondary complications.

Milk fever is a common cause of recumbency in freshly calved cows and is treated with calcium solutions. If calcium is given into a vein too quickly it will kill the cow.

There are many other conditions that can cause cows to go down. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID’s) are often appropriate in the prevention and treatment of many of the secondary conditions that recumbent cows are prone to. These drugs are available only under prescription by your veterinarian.

The response to the initial treatment needs to be assessed by the farmer in relation to the primary condition and its severity. Cows with milk fever should be up and about within a couple of hours whereas cows with severe systemic conditions, such as Salmonella may not have changed much in this time.

Cows that have not improved as expected need to be re-assessed to ensure their treatment was correct. Alert cows that are unable to stand should be lifted, if appropriate.

Some cows will be able to stand and walk away after being lifted. Cows that cannot stand or are not strong enough to lift at this point need to be moved to a suitable nursing environment to maximise their recovery chances.

Secondary damage:

Down cows are prone to secondary damage, especially if they have been down for more than a day, often because of pressure on the muscles and nerves of the hind limbs.

Risk factors are hard surfaces, heavy cows, inability to swap from side to side, and length of recumbency. Damage to the nerves in the back resulting in their hind limbs going out behind them is another common cause of secondary damage.

Other common complications include hip dislocation, paralysis of the nerves in the forelimb, pneumonia, mastitis and bed sores. All of these conditions are associated with poor quality nursing.

Nursing:

Every farm should have a dedicated area set aside for the nursing of down cows, which provides shelter from adverse weather conditions, suitable deep soft bedding such as hay, sawdust or sand; barriers to keep the cow on the bedding and restrict her area to approximately 3m x 3m to prevent her crawling; conveniently located so the cow can monitored regularly and rolled from side to side if needed; and clean and dry to ensure good hygiene.

Down cows need to have adequate feed and water readily available, and enough staff to provide a high level of care.

Many New Zealand dairy farms have limited shed space during calving, so many down cows are nursed outside in paddocks. Using a good quality cow rug will help improve their welfare.

Moving downer cows:

Recumbent cows need to be moved to the nursing area in a way that avoids causing further damage, such as rolling them into a front-end loader bucket whilst ensuring their head is in a safe position, rolling them on to a “carry-all” and tying securely, or carrying them in a sling or hip clamp with a strap under their chest. They must not be carried only by a hip clamp.

Recumbent cows need to be moved to the nursing area in a way that avoids causing further damage, such as rolling them into a front-end loader bucket whilst ensuring their head is in a safe position, rolling them on to a “carry-all” and tying securely, or carrying them in a sling or hip clamp with a strap under their chest. They must not be carried only by a hip clamp.

Lifting:

Lifting should only be done if it is effective and supervised. The cow must be able to stand in a natural position and take about 70% of their own weight. Some cows may be unable to stand and some are unwilling to cooperate. Either way, those hanging in a hip clamp or slouching in a sling without taking any significant weight will suffer secondary damage.

They are better not lifted. Supervision is important to ensure they can be put back down on the ground when they tire and the effective lift becomes ineffective. Cows that are lifted ineffectively or are unsupervised have a poorer chance of recovery than if they were not lifted at all.

Daily nursing cycle:

Cows that are still down on the second and subsequent days can be thought of as having entered a “daily cycle of nursing”. This cycle involves being checked several times each day to ensure their basic needs are being met:

- adequate feed and water

- the environment is kept hygienic

- adequate protection from the weather

- they remain on the suitable bedding

- rolling them from side-to-side multiple times a day if they are unable to do so themselves

- lifting, if appropriate

- continually assessing their welfare.

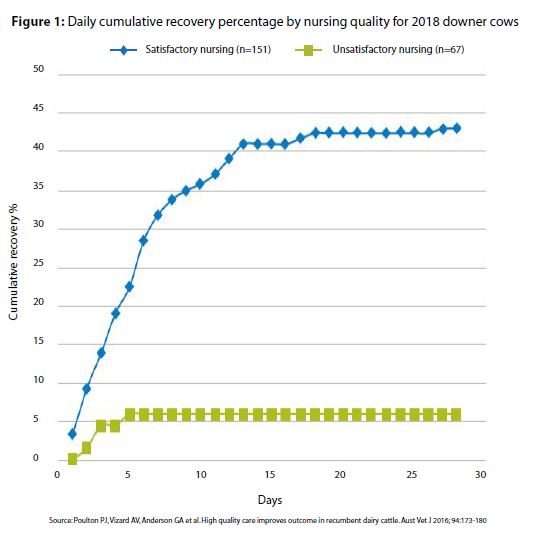

Results from the study showed that the recovery chances of a downer cow that was nursed “satisfactorily” was more than an eleven-times better than those nursed “unsatisfactorily”, as shown in Figure 1. If a high level of nursing is provided to the cow, they are more likely to recover, less likely to sustain secondary damage and more likely to recover from the secondary damage if they are affected by it.

Cows that are nursed well have been shown to recover even after a few weeks whereas those nursed poorly that have not recovered after a few days are very unlikely to recover. If a down cow is to be nursed, do it properly or euthanase them after a few days.

This is an important animal welfare message. If a farmer is unable or unwilling to provide a high level of care then euthanasia should be elected early in the course of the recumbency.

Conclusions:

Many farmers find down cows difficult to deal with and unrewarding. This is often due to the secondary damage that occurs after they become recumbent, which is highly associated with the quality of nursing they receive.

Down cows must be treated promptly and appropriately. If they have not recovered within a short time, they should be moved to a suitable nursing area where they can be cared for at a high level. The welfare of the down cow must be always considered.

Phil Poulton is a veterinarian with Gippsland Veterinary Group, Leongatha, Australia.