Results from a Rangitikei beef and cropping farm spurred a Dannevirke couple to install a woodchip bioreactor on their farm to extract excess nitrate from drainage water. By Jackie Harrigan.

Research on a suite of nutrient mitigation options is getting to the point of results and finding a low-cost option for farmers to extract excess nitrate from their drainage water.

Research on a suite of nutrient mitigation options is getting to the point of results and finding a low-cost option for farmers to extract excess nitrate from their drainage water.

Dannevirke dairy farmers Andrew Hardie and Helen Long were tracking the results of the Massey University research at Hugh and Roger Dalrymple’s Bulls beef and mixed cropping farm and decided to install a woodchip bioreactor on their Te Maunga once-a-day (OAD) dairy farm.

The Bulls bioreactor has been monitored over the past three years and from a site of 90 cubic metres of pine woodchips in a lined pit, the nitrate removal rate was measured at 0.85g/cu m/day, about 28kg N per year.

That rate of outflow/inflow of nitrate-N showed a 64% removal rate of the nitrate by passing through the bioreactor.

While this performance in real terms was lower than Massey University researchers Ranvir Singh and Dave Horne expected, they said the sand country running cattle finishing had a relatively low level of nitrate flowing into the bioreactor and they were heartened by the rate of removal. For Andrew Hardie and Helen Long, the bioreactor offered another tool in the toolbox of nitrate removal and mitigation from their 429 hectare farm which is bordered by the Manawatū and Mangatewainui Rivers.

With a 258ha milking platform milking 700 cows once-a day, the couple, Ballance Farm Environment winners in 2018, have spent the past 22 years developing, draining, establishing wetlands and riparian plantings, production woodlots and retiring native planted land and considered themselves environmentally proactive and good guardians of the rivers and water quality.

A Massey conference piqued their interest in bioreactors for removing nitrates and after the Massey field day they received a grant from Horizons regional council to test the drainage water travelling into a wetland area, draining the artificial drainage system on 65ha of intensive dairy land and the effluent application area. They were shocked at the amount of nitrate-N, up to 25g/cu m in a rain event that included runoff from the races.

“We know that the Manawatu River has not been overly affected because Helen has been testing the river for the catchment group, but we realised that the drainage water is a potential risk as a point source of pollution.”

A $10,000 grant from the Manawatu River Leaders Group helped them convert the wetland into a bioreactor that would be monitored by scientists at the university to capture data on the rates of nitrate extraction.

“Being proactive people, we saw that we could add some good science-based data to the argument, and maybe influence some regulation,” Andrew said.

“Farmers aren’t scared of regulation if it’s based on fact – most farmers have a genuine desire to improve their environmental impact – it’s good for their business. And with a practical mitigation and an independent source of monitoring through Massey University it only adds credibility to the project and the results.”

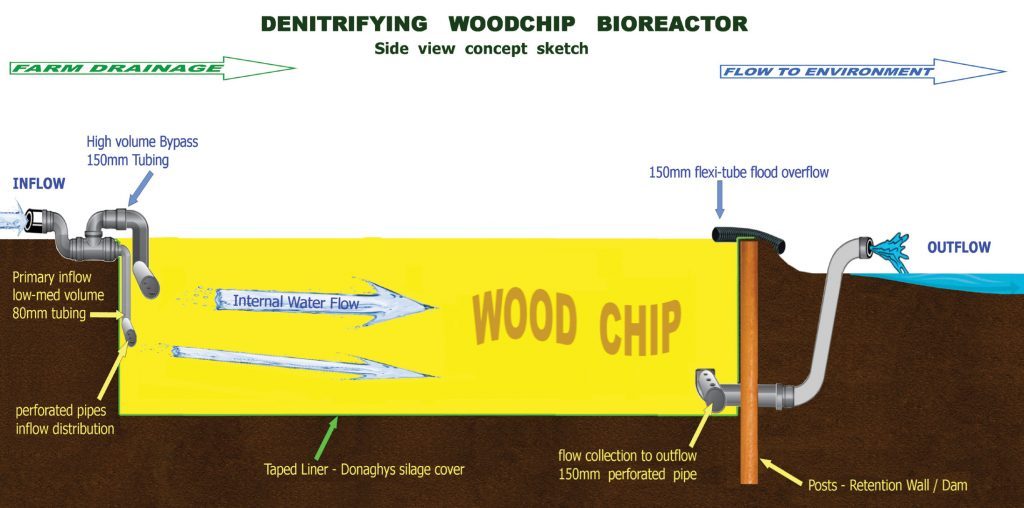

With their own digger and tractor, Andrew and Helen are a great team on a project – he dug the hole with the digger and she moved the fill away with the tractor. They conferred with the Massey researchers, got an idea of the volume required and dug a big hole, lined it with a geotech fabric to cushion any stones, then recycled a couple of old polythene silage covers and filled it with 170 cu m of wood chips.

Their plan to chip forestry slash from a pine woodlot they had harvested was derailed by Covid and the chipper not being available so they bought the wood chip in and spent the grant money that way.

The researchers installed monitoring equipment and covered the bioreactor with a windbreak cloth (to protect the monitoring instruments), but Andrew said overseas the bioreactors are often grassed over. They hope the chip will last 10 years and plan to scrape out the compost and apply it to a crop paddock.

The science behind the bioreactor is simple, Andrew said.

Essentially the hole filled with chips fills up with water and in the anaerobic environment (without oxygen) the bugs take oxygen from the NO3 -N in the water and use the oxygen to eat away at the carbon in the woodchips. The inert N2 gas is released from the bioreactor into the environment and the carbon breaks down over time into composting material.

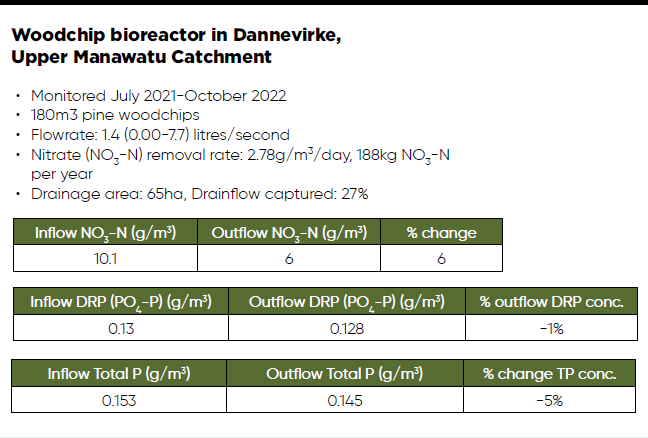

After a year of monitoring, the results from the bioreactor show nitrate-N in the drainage water has been reduced by 40% by passing it through the bioreactor, and 188kg nitrate N is removed each year, from the 65ha treated.

The efficiency is highest at a flow rate of 2-3 litres/second. At higher flow rates the extraction is less efficient and when the water is flowing faster, after rainfall, the excess water bypasses the bioreactor.

Only 27% of the drainflow was captured through the bioreactor, but Andrew and Helen have a plan to increase that.

“The other thing we are looking at doing is building a retention dam (earthwall dam) to hold up the water in a large rainfall dump to allow it to all be slowed down and treated through the bioreactor.”

There is the potential to have a bioreactor at the end of every artificial drainage area on the farm, Andrew said, and he and Helen have identified a further three areas to drain through a bioreactor, lifting the areas treated from about 25% to about 60%.

“Now the technology is proven, we could potentially have a small bioreactor at the end of each of the drainage areas before they reach the river.

“One of the things that we like tothink might happen might be that good policy will be made, based on sound science to actually enable us to carry on farming sustainably, reducing our impact on the environment but meeting regulations.”

Next steps for the research is to expand the number of bioreactors monitored and build capability around designing and specifying the size required to remove a certain amount of nitrate from artificial drainage water.

Edge of field nutrient loss mitigations show promise

A suite of three projects investigated with Sustainable Farming Fund Project funding explored the potential to remove contaminants from drainage water before they reach streams and rivers:

- Woodchip bioreactors installed and monitored in Bulls and Dannevirke

- Controlled drainage in Bulls, coastal Rangitikei sand country

- Drainage water recycling in Bulls, Rangitikei sand country.