Succession planning can be a denial disease, but farmers need to get their heads out of the sand, be brave, and start the process now, say Waikato dairy farmers Brendon and Rochelle O’Leary. BY: SHERYL HAITANA PHOTOS: EMMA MCCARTHY

If farm owners don’t deal with succession while they’re alive, the dust will be rising long after they’re gone.

If farm owners don’t deal with succession while they’re alive, the dust will be rising long after they’re gone.

The family left behind will battle to try and come up with solutions and often end up selling the farm because nobody had the guts to have the hard conversation while the parents were alive.

Brendon and Rochelle O’Leary have seen it happen, with families in legal battles over the farm business. They wanted to avoid that and they also wanted more clarity of their own future moving forward, so they engaged the family in succession discussions.

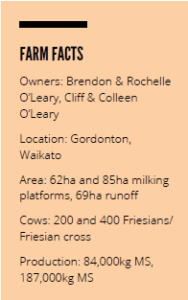

Brendon and Rochelle farm at Gordonton, where they own two dairy farms and a runoff, in partnership with Brendon’s parents Cliff and Colleen O’Leary.

Brendon is the fourth generation O’Leary farmer, with his great grandfather buying a farm at Pokeno in 1911.

Their 87-hectare farm, on O’Leary Road, was a mixture of dairy, beef and market gardening when Brendon started working on it after he left school. He met and married Rochelle in their early twenties. Brendon’s brother Lindsay was also working on the farm, and it became clear the farm wasn’t big enough to support three families.

They decided as a family to sell the farm and move to Gordonton where they bought the new farm as a family company, with Brendon and Lindsay gifted shares.

They grew the business to a second dairy farm and a runoff. Since going through the succession process, Lindsay has now left the business to go in his own direction, with Brendon and Rochelle paying him out of his share.

When Brendon’s parents pass away, Brendon and Rochelle will then buy his brother and sister out of his parents’ share. All parties are now aware how this will unfold when the time comes.

It’s always more difficult if there is one sibling onfarm and two off that need to be bought out, Brendon says.

It’s important to treat family members fairly, this doesn’t necessarily mean equally, they say.

The process has been a roller coaster at times, but they’ve all managed to come out relationships intact, with fair solutions and a clear plan for what happens in the future.

Rochelle and Brendon’s advice to other farmers with succession hanging over them is to start by hiring professional advisors who don’t look to the past, but look to the future instead for solutions to help the family achieve a succession plan.

“You’ve got to have the right people around you – you can’t do it on your own.”

They hired a new accountant and lawyer who could look at the family business with fresh eyes and it was the best move they made.

Every family member was able to meet with them on their own and tell their side of the story and set out what they wanted to achieve from the succession process.

“Through that Dragon’s Den process, everyone gained their voice,” Rochelle says.

Everyone’s own hopes, expectations and needs are different, and it is important that it is all put on the table. However, people need to go into the process open minded and be realistic about the outcome, Rochelle says.

“People can’t expect to go through this and get 100% of what they want.”

There were times when the succession discussions involved just the immediate family and partners sat out.

As a partner, even though she had been part of the business for decades, Rochelle still saw there were times when she needed to step back, she says. People can have different agendas, and it is important that the immediate family discuss how they want things to happen independently.

“You have to put all that sentiment to the side and the emotions – and that’s hard.”

Their professionals, and in particular their ASB rural manager, were essential in keeping the momentum when it came to progressing on succession planning.

Their advice is to find an adviser who can stand in the middle and see everyone’s angle and keep everyone focused. It’s a delicate and at times emotional process, and that adviser needs to be able to manage that as well.

Their bank manager was pivotal in keeping talking with all the parties, including Brendon and Rochelle, Brendon’s parents and his brother Lindsay.

They were the glue that held the process all together, Rochelle says.

“Our ASB bank manager was great at keeping us all focused on the big picture of where we wanted to end up. It’s easy to get distracted by focusing on the little stuff.”

There were some hefty professional fees that needed to be paid as part of the process, but you have to be prepared to pay to get things done and to get it done right, Brendon says.

“It’s going to cost you money, but if you don’t do it, it will cost you more. If you don’t invest now you will sell down your business and everything you had.”

Brendon and Rochelle tried to celebrate the small wins along the way. For example, the first win was getting everyone willing to partake in the ‘Dragon’s Den’ even if they might have gone in with their backs up.

“It’s like riding a roller coaster, you have to be brave. You take two steps forward and then three steps back.”

Brendon and Rochelle’s other piece of advice is not to leave succession planning too late. At 50, Brendon wishes they had been able to have these discussions earlier.

The older generation can leave succession planning too long, their wealth has grown and thus the complexity of their business, and the pie is harder to divide, he says.

“Succession is never going away and it gets harder and harder as your wealth grows and your family grows,”

The older generation fear the loss of control of their asset they have worked for, which can be a big stumbling block in commencing the pathway of succession.

You need professionals to demonstrate to them that this is not the case showing the benefits of a new vision, the couple say.

Brendon’s parents are now in their late 70s and 80s.

“It was too late, we left it too long,” he says.

Succession can be stressful and it’s a lot to take onboard mentally for everyone. He was mindful of not putting too much stress on to his parents and not pushing too hard.

Leaving the succession talks too late also makes it difficult to work out the value the children working on the farm have put into the business over the years.

Brendon’s intellectual property and his input into growing the business to three farms has probably not been truly valued.

“Where was the line that Brendon started adding value to the business? He had all of the responsibility, but not on paper. We grew the pie but we’ve probably missed out on some of that worth.”

Although Brendon and Rochelle didn’t have more ownership of the business legally, Brendon has had the ability to farm with his parents backing.

“We are really grateful for that – they allowed Brendon to drive the business in a new direction, they’ve never held him back,” Rochelle says.

“You must respect the generation that came before. You might not always agree, but we couldn’t be here regardless.”

Brendon feels fortunate that his parents decided to sell the family land and make the move to Gordonton because it provided more opportunities for them to grow and he feels enormous pride to carry on the family legacy of farming.

When it comes to their own children, Alex and Annaliese, they are having open conversations already about succession. Alex is working onfarm managing the 200 cows and they pay him a market wage and keep everything professional.

“Gone are the days when you can expect your children to work for peanuts but ‘one day this will all be yours’,” Brendon says.

Alex will have the opportunity to buy shares into the operating companies of the two dairy farms if he wishes to.

There is a lot of pressure for Alex being the fifth generation and Brendon and Rochelle are mindful of that.

“It can be a burden. You don’t want to be the generation that’s responsible for the business falling apart. There is always a fine line between making your children work too hard, or making it too easy for them,” Brendon says.

Giving too little too late means your children miss out on the opportunity to progress themselves. But giving them too much too early means they might not respect it or handle the responsibility.

With succession, the key is to keep having those conversations and be flexible, Rochelle says.

“Don’t look over your shoulder. Stay focused and continue to evolve. Treat the succession of your business like an open book – there is always another chapter. Our children have not had children yet, so things will continue to look different.”