Rotovirus: A calf-killer

Rotavirus is a major hazard for calf rearers and their charges, Paul Muir writes.

From our calf rearer surveys, we know rotavirus is the biggest animal health issue facing calf rearers with some reporting death rates as high as 30%. We also battled with rotavirus twice and it doubled our calf mortality – from less than 3% to 6.7% and 5.4% in the two years when we had rotavirus outbreaks.

Rotavirus is devastating and demoralising – for both calves and rearers. Since it is a virus, antibiotics are ineffective. Treatment with large volumes of electrolytes is labour-intensive and time-consuming, and not always effective. Even if the animals do recover, they will still shed large numbers of virus particles into the environment, potentially infecting healthy calves.

Recovered calves grow slower and are more susceptible to other diseases, and calves can become reinfected. It is persistent in the environment, and can remain infectious for many months at room temperature. It can withstand low temperatures and high humidity on non-porous surfaces like plastic and concrete.

What is it and how does it kill calves?

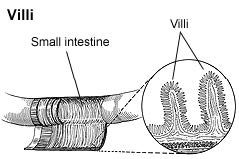

Rotavirus infects and destroys mature cells on the tip of the ‘villi’. Villi are the tiny, finger-like projections on the surface of the small intestine that help absorb nutrients from the digestive tract. Damage to these cells not only reduces absorption of nutrients from milk and electrolytes, but results in fluid loss from the intestine, further compounding the level of dehydration. This dehydration kills calves. Rotavirus increases the concentration of calcium in the intestinal cells which acts like a toxin and results in the pale yellow scour associated with rotavirus.

Rotavirus infects and destroys mature cells on the tip of the ‘villi’. Villi are the tiny, finger-like projections on the surface of the small intestine that help absorb nutrients from the digestive tract. Damage to these cells not only reduces absorption of nutrients from milk and electrolytes, but results in fluid loss from the intestine, further compounding the level of dehydration. This dehydration kills calves. Rotavirus increases the concentration of calcium in the intestinal cells which acts like a toxin and results in the pale yellow scour associated with rotavirus.

How is it spread and what are the signs?

Rotavirus affects calves up to three weeks of age and is spread primarily by calves ingesting faecal matter containing virus particles, but it can also be inhaled, particularly if the shed is highly contaminated.

Infected animals shed large quantities of the virus into the surrounding environment, contaminating the shed area and increasing the risk of other animals being infected. The rate of spread depends on the level of environmental challenge the calf is exposed to but typically between 24-48 hours after infection.

The most obvious sign of Rotavirus in calves is a pale yellow scour, often rancid smelling, this leads to rapid fluid and electrolyte loss and, therefore, dehydration. Rotavirus initially needs to be confirmed with a lab diagnosis but rearers who have already experienced it are likely to identify the presence of rotavirus very quickly.

The key is to identify infected calves very fast, isolate at the start and treat promptly with electrolytes. Make sure you have good hygiene to reduce the rate of spread. At every feed it is important to cast an eye over each calf to identify any potential signs of illness. These may include:

- Hanging back from the feeder/reluctance to come in and feed

- Reluctance to drink, fussing with teat, coming off teat

- Wet tail, pale yellow scour – can sometimes be watery/and bloody

Most calves that die of rotavirus, die from loss of water and electrolytes, rather than the direct action of rotavirus. Rapid treatment with electrolytes is critical.

Scouring continues until the villi inside the small intestine are again covered with mature cells that allow the resumption of normal digestive-absorptive processes. Don’t stop feeding milk but don’t mix electrolytes and milk at a single feed.

It is important to keep the calf’s energy levels up, as well as continuing to provide the calf with antibodies with which to fight the virus. Many electrolytes contain sodium bicarbonate that alter the pH in the digestive tract and adversely affect milk absorption, so milk and electrolytes should be fed at least two hours apart.

Animals may continue to shed the virus in their faeces while not showing clinical signs. Calves do not become “immune to rotavirus” and they can get re-infected. However, the second infection is usually a lot less severe.

Treatment of scouring

Feeding of electrolytes to scouring calves is labour intensive but it is critical to maintain fluid levels. Calves which are scouring and dehydrated need to have the lost fluid from scouring replaced as well as their normal fluid intake. If a 40kg calf has lost 10% of fluid it will need 4 litres just to replace the water it has lost.

While the recommendation to stop milk feeding for 24 to 48 hours remains true for nutritional scours, the recommendations for infectious scours has changed in recent years. Now the belief is that it is important to keep feeding at least some milk to calves especially if they will still drink.

Electrolytes provide energy but no protein and removing milk for any length of time reduces the ability of the calf to fight infection. If milk is withheld for longer than two days the epithelial cells in the gut become dysfunctional and when milk is introduced, the milk itself can cause scouring as it cannot be digested. Scouring calves can lose up to five litres of fluid each day including mineral salts essential for normal body function which is why it is usually the dehydration and acidosis that kills the calf.

Recommendations are to feed milk and electrolytes separately – with at least two hours between the two. If the electrolytes and milk are mixed or fed too close together the milk will not curd and this will increase the level of scouring. Therefore, the electrolytes needed to be administered as extra feeds. This also means that the calf is getting fluids on a more regular basis maximising the potential absorption of the poorly functioning gut.

While electrolytes can be tube fed, it is much better if the calf will drink the milk so that the milk bypasses the rumen via the oesophageal groove.

How do we prevent it?

There is no silver bullet although vaccinating cows against rotavirus and then feeding calves with colostrum and milk from these cows in the first 24 hours helps. This provides the calf with some passive immunity against rotavirus. Unfortunately, the passive immunity declines in the days after birth and there is a risk period before the calves’ own immune system is functioning properly and often the peak incidence of rotavirus infection during this period between five and 14 days of age. Nevertheless, the more rotavirus antibodies a calf gets from colostrum and the older it is before it is challenged by rotavirus, the more likely it is to survive.

Antibodies in colostrum/milk can continue to provide limited local immunity in the gut (even though they can’t be absorbed through the calf’s gut) so feeding milk from vaccinated cows will also help prevent the development of rotavirus.

Hygiene reduces the environmental contamination. Your shed needs to be thoroughly cleaned out at the end of each season and sprayed with a virucide solution. Since the whole idea is to keep the amount of virus contamination to a minimum, spray your shed every three-four days with a virucide solution throughout the risk period (i.e. until the youngest calves are two weeks of age). Many solutions are suitable for spraying over calves.

Maintain a high standard of cleanliness in the shed and thoroughly clean and disinfect equipment such as feeders, especially equipment used in the sick pen. A bucket of virucide can be kept handy to soak bottles and teats in when not in use.

Minimise equipment (including gumboots) and movement between pens with sick animals and uninfected pens especially at the start of an outbreak- once the outbreak is in full flight the shed is contaminated so less important. Initially, try to isolate sick calves away from healthy calves to avoid contamination- this also helps with managing the extra feeds of electrolytes.

Keep a close eye on who is coming into the calf sheds and try to avoid contamination from other farms (apart from people feeding the calves, minimise the number of visitors to your shed in the middle of a rotavirus outbreak). If calves are coming from a number of sources, pen calves from the same farms together and group calves according to age.

Our experience

Our own experience with rotavirus started on August 13 when we had 435 calves in the shed. They ranged in age from new arrivals up to calves which had been in the shed for 21 days.

Within three days of the first case rotavirus being diagnosed, it had spread through the shed, with some calves in each pen affected. Younger calves were hit the hardest but even the oldest calves were affected. However, the older the calf the greater its chance of surviving and we had no deaths in the calves over two weeks of age. In total, 46% of the calves we reared were affected and at the peak it was all hands to the pumps and we were treating over 80 calves. The shed was obviously so contaminated that it was not practical or worthwhile to isolate calves so we stopped trying and concentrated on dealing with the problem.

Most calves were on a once-a-day milk feeding system and we continued to feed milk in the mornings. Any calf that we had any reservations about got a blue neck band so that we knew to monitor it.

Any calf that had a wet tail got a pink band and was fed electrolytes in the evening. Where the majority of the pen had pink bands, it was just as easy to feed electrolytes to all the calves in those pens as chances are the other calves were going to need it soon anyway. Any calf that was wobbly, wouldn’t feed or was down got a red band and was taken to the sick pen.

In total, 8% of calves were taken to the sick pen and 44% of the sick pen calves subsequently died. Overall, shed mortality was 5.4%. Calves in the sick pen were fed milk in the mornings and electrolytes at midday and evening (either by tube or bottle). As a general rule, calves in the sick pen need as much electrolytes as you have time to get into them.

Within 10 days, we had worked our way through the worst of the outbreak but any new calves which were brought into the shed went down within 48 hours in spite of regular spraying of the shed. We felt that we had a very high level of contamination within the shed which was even swamping the good healthy colostrum-fed calves. The only solution was to put new calves into a completely different shed. It is worth noting that we also had three outbreaks of salmonella in the shed. Yet this was quickly recognised as being different, the affected pens were treated with antibiotics and no calf died from salmonella.

Because we had rotavirus problems the previous year, we had sourced our calves from supposedly vaccinated herds. This probably made us over-confident. The pens were clean, calves were happy and we weren’t as diligent as we should have been with the early virucide spraying of the shed. This probably led to the build-up of contamination to the level where it became a major problem.

- Paul Muir and fellow researchers from On-Farm Research, Poukawa, Hawke’s Bay, have been researching the calf rearing market and strategies since 1996.