Salmonella Spikes

There have been some catastrophic outbreaks of Salmonella this year. Salmonella can strike without warning and spread quickly at any time, so what lessons can we learn from these recent outbreaks? Words Sheryl Haitana.

In Partnership with MSD Animal Health

Southland veterinarian Sam Lee had some tough call-outs this spring, including helping a farmer treat up to 400 of their cows for clinical Salmonella, with 10% of those cows dying.

The outbreak has cost the farmer hundreds of thousands of dollars due to the mortality rates, lost milk production and treatment costs.

“We have seen several cases of Salmonella outbreaks on dairy farms and talking to colleagues in different parts of Southland and Otago, the same picture seems to be occurring,” Sam says.

It is hard to predict when or if a farm will experience a Salmonella outbreak. It is not only reserved for farms with in-shed feeding or those going through a particularly adverse weather event. Cows are the biggest carriers of the bacteria and it can strike without warning and on any farm given the right conditions.

Black-backed gulls and waterfowl, particularly ducks, often cop the blame for carrying and introducing Salmonella and there’s some truth in that, but research shows the largest risk to a Salmonella introduction on a farm is the cows themselves, Sam says.

“Overseas research has shown that a high proportion of dairy cows likely have Salmonella already in their digestive tract, but it is not causing any issues. Salmonella is an opportunistic bacteria. If the conditions align that favour Salmonella (external stresses, compromised immune systems), you can suddenly get a scenario where the Salmonella population within a carrier animal will explode.

“That cow becomes clinically unwell and then as soon as you have clinically sick animals, they pass the bacteria in their faeces and other animals get infected by ingesting contaminated food or water.”

There is also research showing that higher levels of magnesium supplementation could have a role in increasing the likelihood of Salmonella, by changing the pH levels in the rumen.

It’s time for reflection for all farmers to sit down with their vets and discuss the risk of it happening on their own farm, Sam says.

“You don’t want it to happen. The consequences of a large-scale outbreak are absolutely catastrophic. It’s a really good time to have that discussion with your vet and see how you can minimise the risks of Salmonella occurring on your dairy farm.”

Vaccination is definitely a big component of that discussion, but it’s also about achieving good cow condition to handle stressful periods onfarm, Sam says.

“We can’t predict and prevent adverse weather patterns, but we can control the controllables – ensuring our cattle are in good body condition coming into stressful periods, making sure we don’t have excessive stocking rates. All those little things help to reduce the risk.”

If there is a Salmonella outbreak onfarm, the difficulty is often it takes several days to process the samples and get a diagnosis, and then vaccinating the herd at that stage takes time for cows to get protection and there will be more sick animals in the interim.

“The real anxious part of dealing with these high-pressure situations is that vaccination itself can take time to work. If you’re already onfarm and dealing with multiple sick animals and you think this could be Salmonella, if you’re waiting for that diagnosis before you act you could be doubling your cases daily.

“Often if Salmonella is suspected, a vet will treat those cows with antibiotics, anti-inflammatories and fluid therapy to try and treat their dehydration and electrolyte loss.”

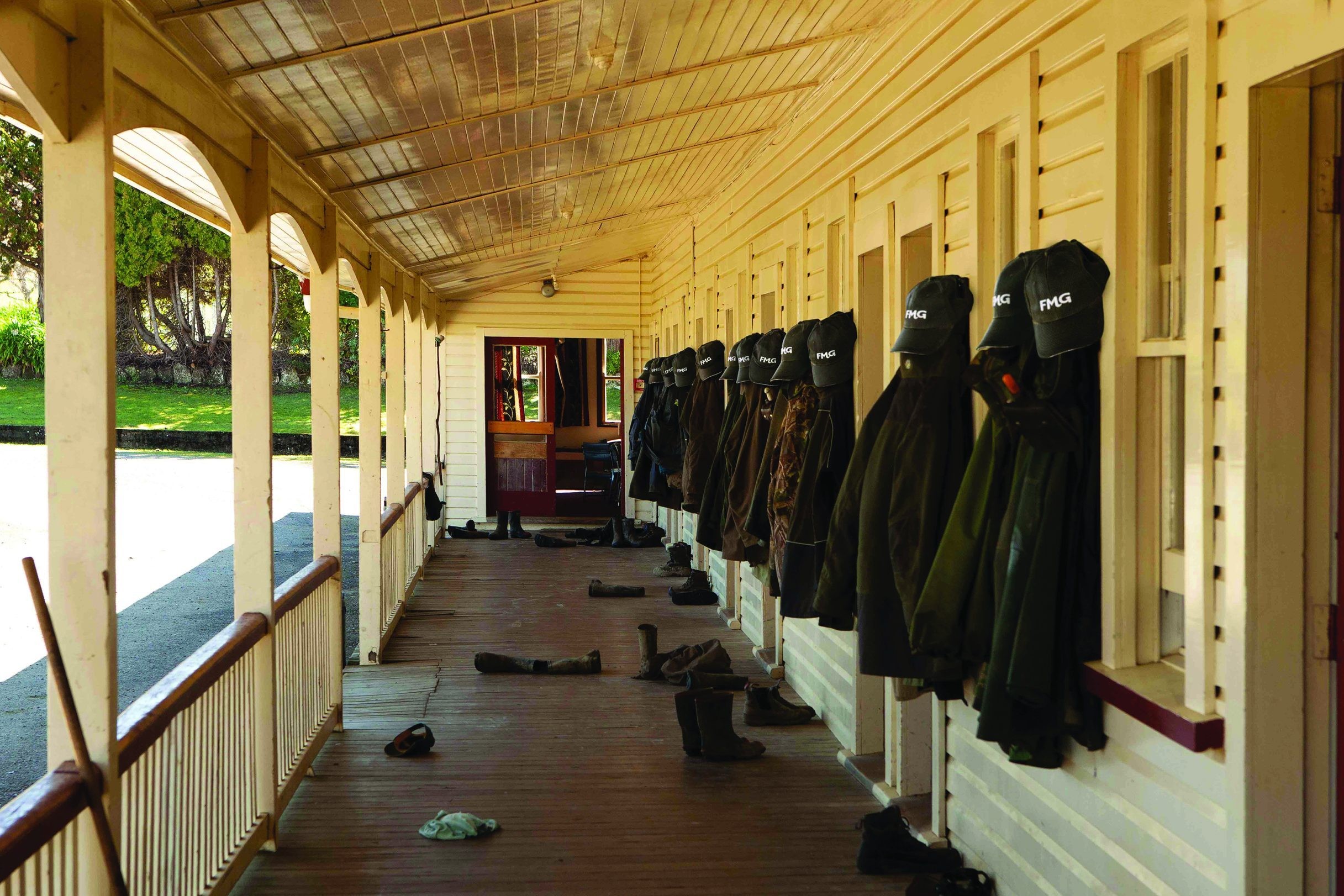

Waikato farmers Louise and Tony Collingwood had their first experience with Salmonella last year when their cows were dried off.

The couple bought a second farm at Ōtorohanga last year and purchased the 470-cow herd, which had previously never had a Salmonella issue.

“Looking back, it was that transition period of drying the cows off and changing their feed, I think that’s why it reared its head when it did,” Louise says.

Several weeks into the dry period their SenseHub Dairy (previously Allflex) collars showed some health alerts for decreased rumination on a couple of cows. They pulled out the cows in question and on closer inspection, they noticed they were scouring, hunched up and really not looking very well.

Cows are the biggest carriers of the bacteria and it can strike without warning and on any farm given the right conditions.

They called the vet out to take some faecal samples and they were immediately given antibiotics. A few days later, Louise got the dreaded call from the vet confirming the cows had Salmonella.

“It was scary, I had heard of herds treating up to 60 or 70 cows.”

Fortunately they were able to find the sick cows quickly, treat them and vaccinate the rest of the herd promptly.

“We were lucky that we had treated the first few sick cows with the right antibiotics and we then vaccinated the entire herd, and the weather was pretty good as well so that probably helped us.”

The herd was vaccinated with Salvexin+B and followed up four weeks later with a second (booster) shot.

“We picked up a few more sick cows when we vaccinated them and so we treated them with antibiotics too. In the end the outbreak cost us a reasonable amount, we treated about 17 cows with antibiotics, we lost a couple of cows and we had about eight cows slip.

“Those cows that had gotten quite sick lost a reasonable amount of weight so our aim was to prioritise feeding them and make sure they gained that weight again as quickly as they could before calving.”

Louise, who was responsible for treating the animals onfarm, also fell sick.

“Even though I wore gloves and followed good hygiene practices, I got sick a couple of days later.”

Going forward, they will follow their vet’s recommendation to vaccinate annually with Salvexin+B to protect against Salmonella.

“This will ensure good protection not only to the animals but also our farm team.”

- Visit bovilis.co.nz/salvexinb