Calving in a compact period gets a stressful period out of the way for a Wairarapa couple. Jackie Harrigan reports. Photos: Brad Hanson.

The reasoning behind an ultracompact calving is a lot like the reason you rip off a plaster – do it fast, get it over with and get on with the rest of the healing.

Calving 90% of their cows in three weeks had the same effect for Matt and Tracey Honeysett from Wairarapa – it was a tough first three weeks and the staff worked hard, but they all opted not to prolong the agony at that time of year.

“The move to compact calving is not all about getting more milk in the vat,” Matt

says.

“Calving is a busy and stressful time of year and we just set up simple systems and processes where we get all our people to come in and smash it out in as short a time

as possible.

“The more you can get it done quicker the better it is – you get it over and done with.

“The difference between picking up 50 calves a day and picking up 70 is not a massive difference – we can shorten it (calving) by two or three weeks at the end.”

The Honeysetts are equity managers on the 1370-cow farm in South Wairarapa, Pahautea Partnership, where the mating length and calving time has been shortened in the six years they have been there.

“We bought the herd with the property and the calving was pretty spaced out,” Matt says.

Moving to the Wairarapa from a lower order sharemilking job in Canterbury, where he said they were aggressive in their mating practices, he and Tracey had decided there would be no intervention in the mixed-aged cows and that it would be very expensive to

shorten the calving time in a season, so they came up with their plan to do it gradually over five years.

They chipped away at the plan and got the farm team on board with it and are now reaping the rewards.

Farm consultant Chris Lewis from BakerAg calculated the tightening up of the calving to mean 9.5% more milk solids, increasing revenue by $367/ha but costing an extra $111/ha in feed costs with a net benefit of $256/ha, which translates to $117,000 across the 460ha operation.

Their mating plan for the 17/18 season was nice and simple, Matt says. Three weeks of sexed semen to bump up the number of heifers born in that time was first.

“That makes life simpler in the spring time – you only have three weeks to deal with replacement heifer calves arriving at the calf shed, and they are all born a similar weight.”

Commenting on the efficacy of the sexed semen he said while its not as good as the unsexed semen, the conception rate was only about 4-5% lower than regular AI, so not disastrous at all. Twenty straws of fresh sexed semen are delivered every three days and used in cows who have calved for more than 60 days, have already cycled once and are young and not in danger of being culled for poor performance.

Commenting on the efficacy of the sexed semen he said while its not as good as the unsexed semen, the conception rate was only about 4-5% lower than regular AI, so not disastrous at all. Twenty straws of fresh sexed semen are delivered every three days and used in cows who have calved for more than 60 days, have already cycled once and are young and not in danger of being culled for poor performance.

“We don’t want to waste the sexed semen on older cows who might be culled at the end of the season.”

The 150 straws of sexed semen guaranteed enough replacements in the first three weeks.

Ten days of short-gestation Hereford semen follows which Matt says is minus five days in the cows and acts as a marker for the staff and calf-rearers, signalling the end of heifer replacements.

Then 10 days of mating with short-gestation dairy semen follow – which further shortens up by 10 days in the cow, and then the bulls were put in to catch any returning cows.

The effect of the short-gestation semen shuffled 186 cows into the first three weeks of calving, that would otherwise have calved in weeks four-six.

The nine weeks of mating resulted in a 11% empty rate, and the Honeysetts had a historical record of 11-12-week mating with 5-7% empty rate.

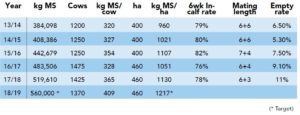

Over the past five years the six-week in-calf rate has ranged from 76% to 82%.

Mating for the 2018/19 season was similar but the bulls have been dropped from the system. Three weeks of sexed dairy semen for replacements heifers will be followed by three weeks of SG Hereford semen and then three weeks of SG dairy semen. The demand for calves in the future and the ability to get away from bobby calves has encouraged the Pahautea partnership to investigate another lease block of 70ha with a view to rearing another 150-200 beef calves in the future.

Farm team on board

Matt and Tracey have a farm team of six plus Matt as equity manager on the 1370-cow farm and say that is the largest team they have had. Two dedicated calf rearers are also employed for the season.

“The farm team just pick the calves up and everything else is done by the calf rearers – they are in charge of the calves and even do the weighing and weaning.

“That can be a reasonably fulltime job through that period, when you are trying to teach 180 calves a day to drink – they do get help from the farm team as well.”

The training and expertise of the team is a major part in the success of the compact calving, Matt says.

“It’s important to have simple systems and processes and get good buy-in from the staff.

“We milk through a 50-bail rotary shed which is our weak link although the technology means it is a one person shed and we structure the roster so that no one is in the shed for more than two hours.”

The herd is split into three herds, with 300 young cows (first-calvers who are milked once-a-day (OAD) for their first lactation) any older skinny cows who need the extra attention to build body condition.

The other two herds are around 500 mixed age cows each.

During mating time there are two people in the shed, one person is at cups-off on the stand and their sole job is detection of cycling cows.

Last year the cows wore ‘Heat Seeker’ pads for the first round and prior to that they used all tail paint.

“We try to run the farm so that everyone can do everything – so everyone was trained in heat detection last year and the AI detection is split into shifts with not one person doing it all – you need fresh eyes.

“If someone is green they might do it with me for three or four days before they get the chance to do it on their own.

“Just like with the milking we split it up so that they are only up there for a few hours then can freshen up rather than sitting up there for five hours.

“There is a concern around spending nine weeks only picking 10 cows out of 1300 each day by the season end – you really need to be aware of not switching off.

“We have thought about the camera technology, but at this stage what we have works – our submission rates are between 88-92%. We don’t really have a target because we don’t want to put pressure on and make the guys worried that they aren’t putting up enough cows.”

The milking regime is similarly structured and simple, with cups on at 4am with the first herd brought in for milking by the first team member and the next team member has the next herd ready to go by 5am and the final herd at 7.30am, when everyone else starts work.

“Each team member only has one early shift each week and they are only in the shed for two hours at a time,” Matt explained.

The afternoon milking starts at 1pm and with only two herds and 1050 cows to milk, everyone is home by 4.30pm.

“We just manage the cows around the shed – it’s a good system – we used to milk 1500 cows under the same system – it worked well then too.”

Fewer cows, more milk

The cow numbers in the Honeysetts’ herd peaked in 2016/17 when 60 further hectares were added to the platform and cow numbers peaked at 1500, producing 328kg MS/cow and 1051kg MS/ha.

A big farm is like a bottomless pit for spending development money, Matt says.

Since arriving six years ago, one pivot was joined by a further three and 50ha of lateral sprinklers to irrigate 260ha and new calf sheds housing up to 380 calves have been developed. An extra 60ha was added to the milking platform in 2016/17 season and cow numbers grew to 1500 at the peak. Numbers came down again over the next two seasons to the current 1370 cows.

“For now we are concentrating on consolidation and improving our per cow and per hectare production, targeting 410kg MS/cow.

“More milk from less cows is the plan although there is a point we won’t want to drop much below as pasture quality suffers if we don’t have the mouths to eat the grass.

“Over time the genetics of the herd has increased a lot – we bought the existing herd and the good (low) empty rates we have had has given us the ability to cull a lot of cows – although we only keep replacements for three weeks we always have plenty around – 23% is the minimum and some years we might keep 28% and sell the excess as in-calf two year olds or sell some cows out of the herd and have more heifers coming through.

“The BW and PW has more than tripled over the six years – we do full DNA testing too which makes everything so much easier around picking up calves – we

have good ancestry and accurate records. And the technology in the shed means we are practically herd testing everyday so we get some really interesting data on the cows.

Chasing cow efficiency

Using the milk production data and daily weighing facility has made it feasible to target cow efficiency, Matt says.

“Two years ago we identified that some of our top producing cows in the upper quartile were in the top 5% for bodyweight and therefore not as efficient as some of the others.”

We went through and sold about 50 cows that were big girls, producing a reasonable amount of milk but not as much per kilo of liveweight as some of the others.”

“We haven’t got big cows, we are chasing efficient cows.”

“The optimum would be 0.9-0.95 so that they are producing almost 1kg of milksolids per kg of liveweight each season.”

“But we are not really concentrating on that right now – but when we have too many cows we can cull on production and also on efficiency too.”

Forage factory

The Honeysetts’ Pirinoa milking platform is like a forage factory, growing 14.6

tonnes DM/ha and renewing 15% of the platform annually through fodder beet or turnip crops or through a grass-to-grass system.

“Pasture is everything for us,” Matt says.

Matt grew chicory for two years four years ago but now fodder beet is grown under the irrigation and fed to the TAD cows up to 6kg/day in the autumn.

The crop is fed in-situ from 22t/ha growing to 28t/ha and Matt says it’s a

cost-effective feed at that level of production.

“It’s not so much extending the lactation for us but holding condition on the cows through to the dry-off on cow condition from April 1 through to mid-May,” Matt says.

“We are only half irrigated so we have a feed pinch in early January-February when we start to burn off across 120ha so our stocking rate goes right up and we won’t get that pasture back until we get the rains come.

“We used to feed turnips – but they are fed through January-February and they kind of burned off after that as well.

“The fodder beet is for filling the feed hole in January-February until the autumn rains bring the pastures back.”

The silty loams and clays are heavy soils, so some cows are wintered off on the runoff and 40ha of sandhills are a real asset through the milking season when they are used as a standoff area in a wet spell.

Equity stake

Matt and Tracey Honeysett bought in to the Wairarapa equity partnership as they could see the potential in the long-time converted property.

They had been lower-order sharemilking in the South Island and won Farm Manager of the Year in 2009 and Sharemilker of the Year in 2015 for the Wairarapa-Hawke’s Bay region.

“While we weren’t really looking for an equity position, we could see the potential as the farm was bought at the lower end of land values and had heaps of upside.”

The partners agreed to pay no dividend for the first three years so they could reinvest in the property and infrastructure and with no end timeframe to the partnership, Matt says it is working well.

“We were nervous about the lack of exit time but the partners are all farmers and they understand both the seasonality of the industry and the mechanics of being in an equity partnership.

The partnership is well-set up, with a chair, quarterly, minuted meetings and Matt distributes a monthly financial report and one-pager on the farm performance.

“Apart from that we are left to our own devices.”

The couple are able to increase their shareholding as they wish and while they were thinking of looking for other opportunities, things changed for their family two years ago when one of their sons contracted a virus which severely paralysed him overnight.

Eli is now back at the local school but requires high-level medical attention which Matt says has changed their focus.

“Our goals have changed as that meant I needed to step back from being so hands-on on the farm.”

With compact calving systems bedded in and farm staff trained to step up, the couple are appreciating the opportunities open to them within the equity partnership and support given to them from partners and from the local community.

Farm facts

- Pahautea Partnership

- Four equity partners, Matt and Tracey Honeysett: equity managers

- Milking platform: 460ha, 260ha irrigated

- Runoff: 60ha on platform, 380ha separate support block

- Cows in milk: 1370

- Cows wintered: 1425

- Milk production/cow: 410kg MS/cow, 1220kg MS/ha

- Target: 560,000 kg MS KgDM/kgMS 15.9

- Dairy: auto cup removers, auto weigh and draft, Protrack, milk and cell count meters

System 3, grass silage, 450kg/cow homegrown barley fed in shed. - Seasonal pasture growth: 14.6 t/ha

Results of ultra compact calving

From first 16 weeks of supply:

- 9.5% more kg MS

- Revenue up $367/ha

- Requires an extra 316kg DM/ha

- At 35c/kg DM this costs $111/ha

- Net benefit $256/ha or on a 150ha farm, net benefit $38,400.