The last two years have been stressful on Hawke’s Bay farmers, with a tuberculosis

outbreak, Covid-19 lockdowns and severe droughts. Tutira farmer Campbell

Prendergast had one R2 test positive for TB in 2019 and has since changed his entire

operation. He talked to Sheryl Haitana about the realities and frustrations.

Campbell Prendergast has been left questioning where his levy money has gone and whether Ospri has enough funding to do the job properly.

He has been disappointed with the follow-through from Ospri on pest control since the TB outbreak in 2019. He says they haven’t done as much pest control as they said they would.

“I think multiple things have fallen over. There should be more intensive pest control and more testing.”

Campbell also feels let down by the organisations he pays levies to, DairyNZ and Beef & Lamb NZ, who are shareholders in Ospri, and should be accountable for ensuring good pest control and testing is taking place, he says.

“I shouldn’t have to be at these meetings beating the table, they should be doing it. It’s been two and a half years and we still have infected herds, and all they keep saying is we are on track to be TB-free by 2026.

“I feel like farmers have been doing everything they can do, with Nait recordings and testing. “But it feels like the wheels are turning, it’s costing money, but the job is still not being done.”

Ospri were too slow on implementing pest control after the first lot of infections, Campbell says.

Ospri are only just gaining access to two new blocks – one in the Waipunga area and the other in Esk Valley, which haven’t had pest control for more than 10 years.

Ospri just keeps changing personnel and hiring new communications people that just don’t communicate well enough with farmers, he says.

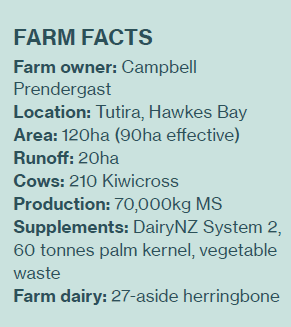

The Prendergast farm at Tutira, 50km north of Napier, has been in the family since Campbell’s grandfather received it through a ballot after the Second World War.

The farm switched from dairy to sheep and beef when the wool prices were good, fully converting back to dairy in 2008.

Campbell moved back to the family farm when his parents converted after working in forestry management for 15 years.

He has a 20-hectare runoff which borders Lake Tutira, surrounded by forestry which has been getting harvested. That is where his rising two year heifers were grazing when one was infected with TB.

The herd has always had a C10 status (clear of TB) until their first-ever positive skin test in February 2019.

“We’ve had neighbours have a case of TB over the past 20 or 30 years, but we had never got it.”

He was one of the first farmers picked up in the area in the recent outbreak.

A standard TB skin test found one rising two year old in-calf heifer. She was blood tested in March and slaughtered on site. The blood test was a low reading.

“The lesion was so tiny, she wouldn’t have been found if she had gone to the works.”

In April the herd was suspended and on May 17 it was classed as an infected herd.

The herd then had a clear skin test on May 21 and another in November, and after a clear blood test in December the suspension order was lifted and the herd were reclassified as C1. Campbell kept the rest of his heifers at the runoff until he had a clear test in May before bringing them back to the milking platform.

“I wanted to keep our neighbouring farms safe. I also had heifers to sell, I wasn’t technically infected in March and April, but morally I felt I couldn’t sell any animals to other farmers.”

Campbell used to winter some of his herd on the runoff and others on neighbouring farms, but he was no longer able to do that and had to buy extra winter feed.

His herd has since dropped from 250 cows to 210 to manage the extra cows at home during the winter months and his production has subsequently dropped.

He has stopped doing winter and summer crops and has instead sowed 10ha of lucerne, which is great feed from late September though to May while the cows are milking, and still offers a little bit of winter feed for the dry cows.

“It changed my whole system over a couple of years. It would have cost us between $200,000 and $300,000.”

Compensation has been limited for farmers and it doesn’t take into account all of the other losses farmers endure, Campbell says.

For example, he hasn’t been able to continue selling surplus colostrum to other farmers for calf rearing. He also shot surplus calves on site that year because getting bobby calves picked up was an extra rigmarole. The farm remains in the livestock movement control area, which puts extra restrictions on farmers and limits their options. To sell any stock, Campbell has to arrange a pre-movement test 60 days beforehand, unless they are going to the works. It means any stock sales have to be planned in advance, and it’s harder to react quickly in situations like the recent droughts.

“It takes a couple of weeks to book a test, so you have to anticipate when you want to sell them.”

Once you’ve had an infected status and have had to start again at C1 status, the selling market is limited anyway, Campbell says.

The price offered for animals within the restricted movement area is usually less as well.

“Nobody wants to touch you with a barge pole. We wanted to export heifers, but it’s only now we are almost C3 that they’ll take them.”

Campbell has been working with Ospri and going to meetings to try and ensure other farmers don’t have to go through the stress of finding a positive TB result.

“If there is something I can do to prevent another farmer going through this I’ll do it.”

Resilience amongst it all

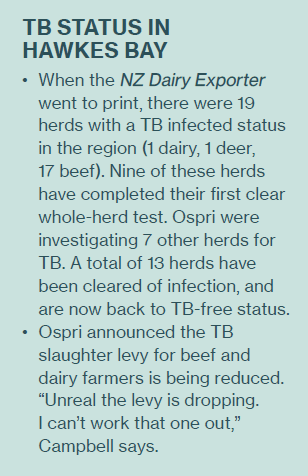

Hopefully this will be the last year Hawke’s Bay goes backwards in terms of TB infections, but farmers are still facing years of disruption, Kevin Mitchell of Rural Support Trust says.

It will likely be another couple of years before the restricted movement area shrinks and even longer for the farms that will be close to the infected area.

There has not been enough compensation for farmers who have had to make drastic changes to their operations or stock classes, to cope with the TB restrictions, Kevin says.

“We were trying to bring it in line with compensation for M Bovis, but we met a brick wall in Wellington. The government doesn’t want to go down that rabbit hole.”

Ospri has offered business support to farmers and has become more flexible with movement of young stock, however.

The slow response from the industry to get on top of the TB infection has been a bitter pill for farmers to swallow, Kevin says.

“Ospri has flacked a fair bit of criticism. But we have to move on. The Ospri personnel have all changed, and they are really listening to the farming groups now.”

There have also been some big wins in being able to get on to blocks to do pest control, which will hopefully combat where this TB infection has come from.

Throughout such a difficult two years, farmers continue to rally and get on with the job.

“Between droughts, Covid restrictions and TB restrictions, 2020 was a hell of a year to be caught with TB. But farmers are pretty resilient and we are getting around and helping where we can.”

Ospri 10 year plan

Ospri has recently completed an aerial bait drop over 10,000ha of private, forestry and public conservation land in the Waikoau area and another operation will commence soon on about 5900ha in the northern Hawke’s Bay, Ospri general manager, North Island service delivery Dan Schmidt says.

“In order to achieve sustainable freedom of TB in livestock in Hawke’s Bay we need to be working in the area for the next 10 years, so building constructive long-term relationships with landowners is paramount to that success.

“We are confident that the agreed plan for work being undertaken will reach TBfree outcomes for the TB response in the Hawke’s Bay but it takes time.”

Ospri is working hard to rid the Hawkes’ Bay region of TB as quickly as possible, including removal of movement control restrictions, he says.

Ospri is investing $20m over five years into pest control, including aerial and ground control work with the aim to still achieve TB-freedom in cattle and deer by 2026.

“Although it’s difficult to estimate exactly when Hawke’s Bay will be rid of TB, the combination of planned pest control work and diagnostic testing of herds will ensure that we are moving closer to that goal.

“We know that these are very trying times for farmers and we feel for them and the situation in Hawke’s Bay, particularly when it’s looking like there will be another drought this summer. We work alongside farmers and regularly meet with them to gain better insights and learn how we can provide support.”