Squeezing fertility

Farmers should have a plan leading up to mating to minimise the hangover of yet another difficult season and what it will do to their reproductive results. Many cows were milked longer leading up to this season to take financial advantage of grass growth, but it could all catch up with them at mating, LIC’s Jair Mandriaza says. Sheryl Haitana reports.

It feels like water is seeping out from the ground across New Zealand after a very wet 12 months as dairy farmers continue to pull on their wet weather gear and drudge through the mud for another calving and mating.

It feels like water is seeping out from the ground across New Zealand after a very wet 12 months as dairy farmers continue to pull on their wet weather gear and drudge through the mud for another calving and mating.

As well as the weather, high interest rates, increased farm working costs and a falling milk price, it all has been pretty exhausting for farmers. And yet how tired are the cows? Many farmers milked longer this year to capitalise on the green grass in front of them and now after a mini break, those cows need to reach BCS targets, calve, hit peak production and then get back in calf at the earliest opportunity.

That temptation for a lot of farmers to keep milking deep into the season, especially with the feed available and the financial pressures on them, was understandable, LIC’s senior reproduction solutions advisor Jair Mandriaza says.

“But there is a risk farmers have already impaired next year’s reproductive and productive performance of their herds.

“Farmers have been struggling to put body condition score (BCS) on once they were dry. This coming season is shaping up to be quite challenging again as an industry.”

Farmers will need to take stock and consider using strategic farm management to strive for better reproductive results.

It would be a good idea for farmers to BSC their herd and work out where they sit heading into calving and identify cows that need some preferential treatment in order to get back in calf, he says.

Farmers will still be feeling their reproductive results from last year too, which will also impact this season’s mating results.

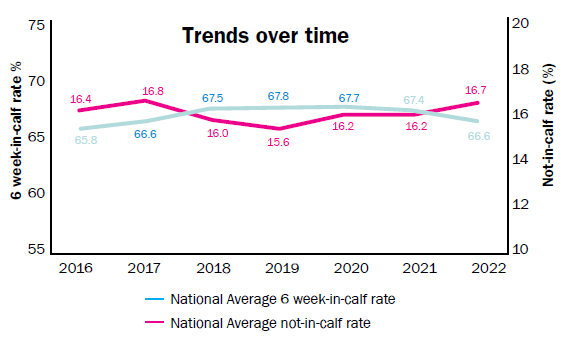

The 2022 national reproductive results showed a national six-week in-calf rate of 66.6% and a not-in- calf rate of 16.7%. The increase in the not-in-calf rate by up 0.5% from the previous year, was most likely due to the wet spring and autumn last year, Jair says.

The key message to take out is when there is a significant event, such as bad weather, you need to be proactive, he says.

Farmers should review the prior season and plan to implement, rather than trying to come up with a plan on the spot when the pressure comes on during the season, he says.

If farmers acknowledge they did milk longer and realise their cows are not at their BCS targets they need to be proactive to rectify it, he says.

“Being proactive is key. If we do what we always do, things are not going to be prettier next year.”

Management is going to make the biggest difference and farmers can identify at risk groups to give some preferential treatment.

Often farmers swear by milking their younger cows or lighter cows on OAD, Jair says.

Unfortunately there are no records of how farmers strategically milk some cows on OAD and what the impact is on reproductive results.

“We don’t have any visibility on that anywhere, but farmers when we are talking to them, they swear by it.”

Herds that milk OAD year round have an 8% higher submission rates, 8% higher conception rates, an 11% higher six-week in-calf rate and a 5% lower not-in-calf rate.

Late calvers need special care

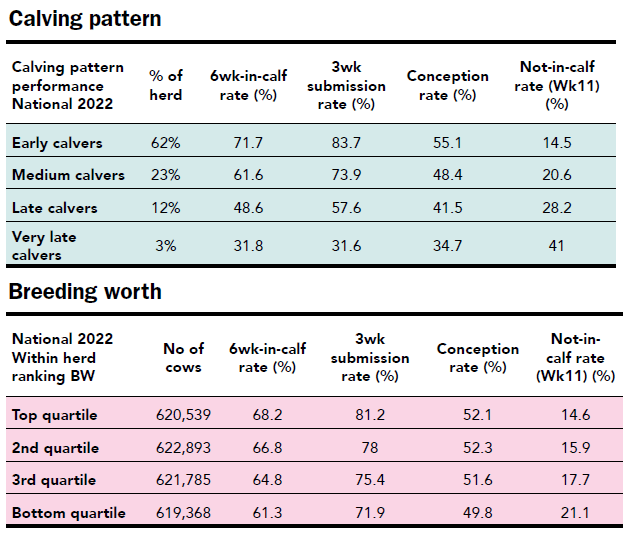

One key group farmers should consider giving preferential treatment to and managing differently is their late calving cows, Jair says.

“As farmers know, early calving cows get in calf well. We do have some work to do with cows calving later.

“Think about late-calving cows as a risk group of animals and if you treat them just like you treat the early and medium calving cows, they’re going to underperform. They do need some pampering of some form in order to minimise their impact on the herd’s reproductive performance. Otherwise you can expect a lower six-week-in-calf rate and a higher not-in-calf rate.”

A lot of the time cows have got to the point of being a late calving cow through no fault of their own, he says.

Once they fall into that group their ability to get in-calf reduces and it becomes hard to reverse their fate, doomed to continue to get in calf late and eventually ending up on the cull list.

When it comes to putting cows on OAD as a management tool, farmers get concerned by a drop in milk production, but perhaps they would be better off financially in the long run, he says.

“Farmers are concerned about losing milk production, I always say late-calving cows have less days in milk, so the investment into preferentially treating them by putting them on once-a-day won’t cost as much because the bulk of the milk production is being done by those early and medium-calving cows.

“They may lose some milk production, but from a cow’s lifetime production point of view, if she can get in-calf earlier the following season she will give heaps of days in milk. She will pay you back.”

For farmers to improve their overall herd’s reproductive results they need to be able to improve their not-in-calf rate so they can have more selection power and continue to improve the herd.

“If you can’t manage your not-in-calf rate you can’t cull those animals off your system.

“If you want to reduce your not-in-calf rate you have to improve your 6-week in-calf rate; they go hand in hand,” he says.

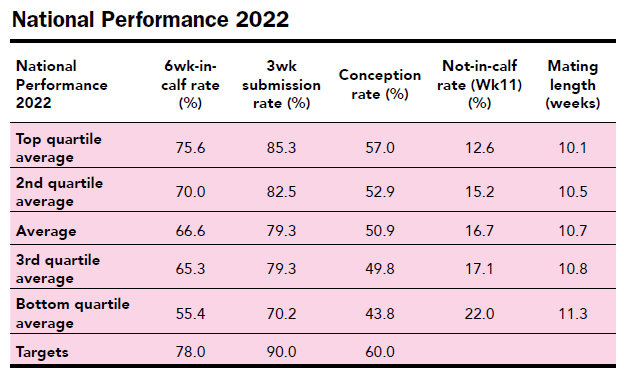

The national six-week in-calf rate of the bottom quartile cows is 55% and the not-in-calf rate is 22% which means the rest of the herd has to go really, really well to average that out, to dilute that impact.

Drop out the low producers

One of the key opportunities for the dairy industry when looking at the production table, is keeping the top three quartile cows and target discretionary culling within the bottom quartile. The bottom quartile are producing 140kg milksolids (MS) less than the top quartile, and 40kg MS/cow less than the third quartile.

“Imagine if you could work towards replacing those animals with cows achieving the same as even the third quartile. That’s an extra 40kg MS/cow in that bottom quartile, that mounts up very, very fast.”

That also improves the average of the herd’s reproductive performance greatly.

Farmers can use their Fertility Focus along with Minda Repro to look for at-risk groups and identify areas of opportunity, Jair says.

“If they have Minda Repro, they can delve deeper into calving patterns, performance of age groups, the influence of BCS, health events etc.”

“I’d definitely encourage farmers to use it. We can identify specific groups in the herd that are not performing as well.”

Breeding vs management

The overall national reproductive performance picture is showing what it should, the top BW and PW cows are reproducing the best, along with the younger cows in the herd, which is all to be expected.

The message is clear to keep breeding good cows, but management is the other half of the coin.

“When we look at the difference in fertility breeding value, the difference between the 6-week-in-calf rate of the top and bottom quartile is 13%.

“Breeding value does not count for a 13% difference. The management of the cows can help mitigate the poorer performance of lower fertility animals.

“What I see in herds that have good reproductive performance, they end up getting the six-week-in-calf gap between top and bottom quartile to around 6-8%.”

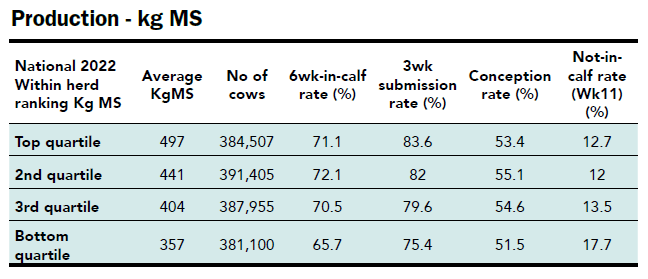

On the national results, the higher-producing cows are also performing better reproductively than the lower-producing cows.

The top three quartiles of cows in NZ when it comes to production have very similar reproductive results, sitting around 70% six-week-in-calf rate and the bottom quartile has a 5% lower six-week-in-calf rate and a 4% higher not-in-calf rate.

“What that tells me is as long as cows are being given enough energy through the system, a cow that produces you a lot of milk, gets in calf as well. She’s effective at producing and reproducing at the same time.”

Farmers often identify their top-producing cows based on their first herd test of the season and believe they are not good at getting back in calf, however, it’s important to remember the best producing cows have usually peaked by that herd test, Jair says.

“Cows that are peaking come herd testing time are often cows that calved late. A lot of the cows that calved earlier have peaked and are more stable by that October/ November herd test.

“They look like they’re producing a lot but they’re late calving, and that is what is hampering their ability to get in calf, not their milk production.”

Where are we sitting?

The not-in-calf rate has been hovering between 15.6% and 16.8% for a number of years.

Farmers still talk about empty rates, which is the number of cows showing empty at pregnancy testing, however, the not-in-calf rate also includes cows that were in the herd at the start of mating and may not make it through to pregnancy testing. That means the not-in-calf rate is about 3-4% above a herd’s likely empty rate.

The decision to use artificial breeding (AB) through the whole mating period or use a combination of AB and natural bulls is not influencing reproductive results either, Jair says.

Herds that are mated all AB had a not-in-calf rate of 16.7% versus AB plus bulls which was 16.69%.

The average mating length nationally is now 10.7 weeks. Herds that are mating with all AB are often mating for slightly longer, 11 weeks as they are using short gestation semen.

After week nine, every week farmers extend mating is worth about a 1-2% lower not-in-calf rate.

“So if a farmer can go a bit longer but still calve within a short period of time they will benefit from more cows in calf.”