By Louise Hanlon

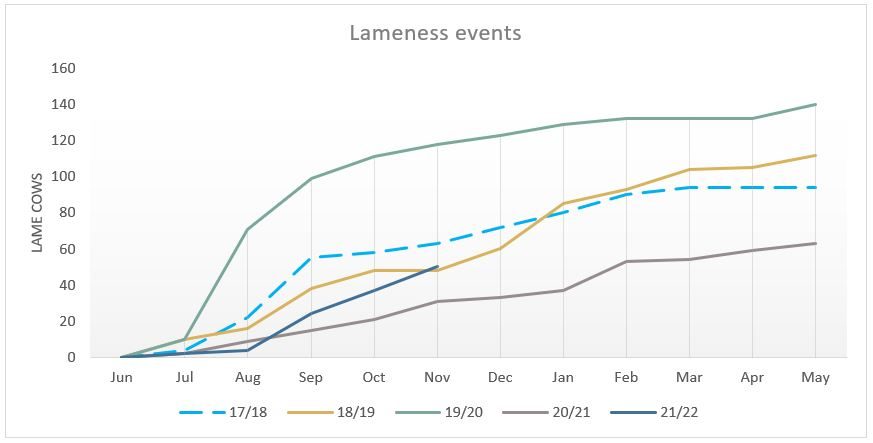

An escalating lameness problem on Owl Farm came to a head in March 2020 with 34% of the herd identified as lame over the course of the season.

The number of lame cows had been growing over the previous couple of seasons, and it was causing concern due to its impact on animal welfare and productivity. This prompted the farm team to instigate an in-depth investigation into the issue. Since then, actioning a programme of changes has turned the situation around.

Owl Farm is owned by St Peter’s School Cambridge, and is also a demonstration farm, which means the process for releasing investment funds is more involved than for a typical farm, with a detailed justification required before the management committee will give the green light. However, this does mean the process they use to investigate issues and opportunities is rigorous and generates strategies that other farm businesses can use as well.

The initial step involved getting a handle on the financial impact of the issue. DairyNZ has developed a tool to help with this process, the Lameness Cost Calculator, which is available on their website. The calculator indicated that there was the potential to gain $57,000 from tackling the problem.

Next, they engaged the services of Healthy Hoof Provider, Bill Hancock, from Cambridge Vets. Healthy Hoof is a programme administered by DairyNZ which aims to help farmers to get on top of lameness problems through following a structured process, with the assistance of a trained professional.

After discussions with Hancock they set up a white board to record the incidences of lameness, which hoof they occurred in, and any treatments used. After looking at the recorded information they concluded that the majority of cases were due to white line disease.

“White line is generally a disease of cows under pressure,” Hancock says. “They are either having to push forward out of that pressure, on the yard, the raceway, or feedpad, or back out of a situation. They can potentially get white line disease whenever they have to turn, push, or compete.”

They also installed a GoPro camera on the roof of the milking shed to record footage of cow behaviour on the yard, as well as how the milkers managed cows during milking. The footage was revelatory.

It was clear that having all the cows in each herd entering the round yard from the back and filling up both sides was causing the cows on the right hand side of the yard, behind the gate, to turn around 180 degrees before they were able to move into the free space on the yard. As a result, they decided to place the backing gate in the middle, so that cows still entered both sides, but the backing gate only took up the space behind the cows on the left hand side that were already facing towards the entrance.

This gave time for the cows on the right to turn around and follow the backing gate around before being followed up by the second backing gate. The cows were less crowded, had time to turn to enter the platform, and cow flow improved.

A mirror was also installed above the pit so milkers could see the yard without going up the steps to look.

“Going up the steps to see what was happening had the negative effect of entering the cows’ flight zone,” says Tom Buckley, Owl Farm Manager.

“Milkers can now look in the mirror instead and this drives when they use the backing gate. It is much better if cows are trained to enter the platform themselves, rather than being pushed in by people, as that interrupts cow flow. We also have a timer and a buzzer on the backing gate so it doesn’t get left on too long, or push them too hard.”

Any signs of lameness are managed proactively, with Buckley’s homemade hoof blocks used to treat any white line affected hooves where the disease isn’t on the heel. Focusing on treating issues early helps to ensure cows spend as little time as possible in the lame cow mob.

Well-designed handling facilities make a big difference as well.

“Having good facilities, with a roof and good lighting, is important as it makes it safe for the cow and the operator,” Buckley says. “And it makes it easier, which means people are willing to get cows up early for treatment. The vet is called out for more complex issues – this is also a good opportunity for staff training. They can learn about treatment, trigger points, when it is necessary to call a vet in, and how you can manage and record lameness.”

The final step in the programme of changes involved assessing and improving the race infrastructure. First, the team divided the races into priority areas, after looking at their current state i.e. gradient, trees, and drainage; and the amount of traffic they handled e.g. races near crop paddocks were high traffic zones, and some sustained more vehicle traffic than a typical farm because of Owl Farm’s demonstration role. Then the races’ issues and their remedies were identified. The changes made a notable difference. “It takes the cows about eight minutes to get up a hill that used to take 40 minutes,” Buckley says. “We budgeted around $30,000 of capital input, with some additional spend year-on-year for maintenance. We were also able to plan out three years in advance.

“When changes couldn’t be made immediately we problem-solved. For example, the slopes in and out of the underpass were getting worn away quite quickly in spring, and contractors were unavailable at the time to come and fix them, so we used AstroTurf to reinforce them.

“This was really effective, and easy to wash, with any flow-off getting collected in the sump. AstroTurf was also effective on the areas getting wear around the feed-out areas on the races and the junction between the race and the yard.

“It’s important to proactively tackle challenges by watching cow behaviour and identifying the possibility of issues.”

The end result of the whole process has been highly satisfactory, with a drop to 15% lameness in the herd in the season following the programme implementation.

Even though the start of 2021-22 has proved challenging, with 599mm of rainfall to mid-November (compared with 420mm last season), the changes have ensured that lameness continues to trend lower than the past two years. The team isn’t resting on their laurels though, as their ultimate goal is to reduce lameness to below 12% annually.